The Affair↑

From December 1914 onwards, Colonels Karl Egli (1865-1925) and Friedrich Moritz von Wattenwyl (1867-1942) – both leading members of the Swiss General Staff – began to covertly hand over sensitive, decoded Russian diplomatic dispatches to the German authorities on a regular basis. Additionally, from February 1915 onwards, they also shared confidential Swiss military bulletins with the German and Austro-Hungarian representatives in Berne.

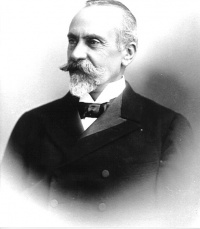

Yet, the Swiss government was not aware of this delicate form of cooperation, until André Langie (1871-1961), a renowned cryptograph responsible for decoding the dispatches, realized that the Russian dispatches he was decoding would most probably be transferred to the Central Powers. In his view, Colonels Egli and von Wattenwyl were violating and endangering Swiss neutrality, which had been proclaimed at the beginning of the war. Langie, from the French-speaking part of Switzerland, informed two leading French-speaking journalists – Albert Bonnard (1858-1917) and national council Edouard Secretan (1848-1917) – at the end of November. Following Secretan’s advice, Langie informed the Swiss Federal Council of his findings at the beginning of December 1915. The Russian and French ambassadors in Berne lodged an official complaint shortly afterwards.

Press Campaign and Scandal↑

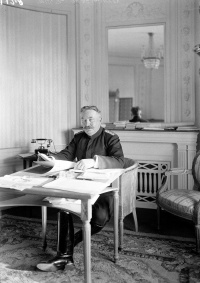

When the Germanophile Swiss General Ulrich Wille (1848-1925) was officially informed about the matter by the Federal Council, he initially tried to cover up the affair: Egli and von Wattenwyl were discretely removed from the General Staff and redeployed to other posts within the army. However, the French-speaking politicians who had also been informed by Langie were not satisfied with the way the army leadership handled the situation.

Together with other journalists and politicians, they decided to take the matter further. On 14 January 1916, the affair was made public with an editorial in the French-speaking newspaper La Sentinelle. The social-democratic, German-speaking and army-critical Berner Tagwacht and the Volksrecht followed the next day. Resulting mainly from the internal divide between the French and German-speaking parts of the country and the international situation, the press campaign marked the beginning of a political scandal which shook the Swiss political scene to its very foundations. The affair dominated public debate for more than two months.

The Trial: Violation of Neutrality?↑

To a great part of the francophone population and politicians of Switzerland alike, the cooperation with the German and Austro-Hungarian intelligence agencies clearly violated Swiss neutrality. The following cover-up strategy of General Wille was perceived as a blatant example of the pro-German sentiment within the military. Under an ever-increasing public pressure, the Federal Council forced the General to take further steps and to start legal proceedings in a military court. The trial finally took place in Zurich on 28 January 1916. The two colonels were charged with violation of neutrality and misconduct.

In the course of the trial, von Wattenwyl and Egli did not deny having delivered the bulletins, but argued that this had been necessary in order to get important intelligence information from the Central Powers in return. The more delicate deciphered Russian dispatches, however, were not at the core of the trial.[1] Both of the accused colonels even denied the exchange of such documents. The pair was eventually acquitted by the court and left to be disciplined by the General, who sentenced them to the maximum penalty of twenty days of arrest. The Federal Council then dismissed them from the army.

Relevance↑

The trial, which was orchestrated and influenced by the German-friendly army leaders and the government, did not calm public sentiment. On the contrary, the acquittal reinforced the distrust that sections of the population already felt towards the army. In the short-term, it also seemed to deepen the rift between the French-speaking and German-speaking parts of Switzerland. Most of the francophone and social democratic newspapers expressed great indignation at the verdict. In the following session of parliament, primarily French-speaking representatives protested strongly against the politics of the government and the army leadership. They demanded the limitation of the Federal Council’s extraordinary powers (“Vollmachten”) and even called for the dismissal of the disputed General Wille. Due to the lack of willingness of the Federal Council and the majority of German-speaking parliamentarians, these initiatives finally failed.

As a consequence of the affair, the relationship between the Federal Council and the army leadership became increasingly strained, which in turn also strained the relation of the Federal Councillors among themselves and weakened the government in time of turmoil. The government subsequently reduced the influence of the Germanophile army leadership on domestic policy and recalibrated military-civilian relations after the parliamentary session in which the affair was discussed. A year later, this tendency was amplified, as the French-speaking and Entente-oriented Gustave Ador (1845-1928) was elected to the Federal Council. The Election was, on the one hand, an important goodwill gesture for the Entente, on the other a sign for a stronger integration of the French speaking part of Switzerland into the political system. Thus, in the long run, the events might even have contributed to the cohesion of the different language groups in the further course of the war.

In contrast, the affair enhanced disintegration along social and political lines. Shortly after the “Oberstenaffäre” (colonel’s affair), the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (SPS) handed in a popular initiative which demanded the abolishment of military justice. This initiative played an important role in unifying the party in regard to military policy. Therefore, the affair was a turning point for the social democrats in the path from the party truce at the beginning of the war towards a categorical refusal of national defence in 1917.

On an international scale, one can say that there was a certain degree of enhanced military threat during the crisis. French military strategists simultaneously developed plans to cross Swiss territory into Germany (“Plan H”). However, the German offensive at Verdun led the French leadership to finally drop the preparations. For the Entente, and particularly for France, the affair was in fact a chance to revitalise the then strained relations with Switzerland. Without giving up the ties to the Central Powers, the first secret military talks about a military cooperation in the event of a potential German violation of Swiss neutrality followed in June 1916.[2] The affair therefore contributed to a gradual change of Swiss neutrality, as the country began step-by-step to shift towards the Entente.

Sebastian Steiner, Universität Bern

Section Editor: Daniel Segesser

Notes

- ↑ Langie was not able to present solid proof in court and contradicted himself on certain points. But it was in the interest of the government not to place a special emphasis on this point. See Fuhrer, Hans Rudolf: Die Schweizer Armee im Ersten Weltkrieg. Bedrohung, Landesverteidigung und Landesbefestigung, Zurich 2003, p. 220.

- ↑ Ehrbar, Hans Rudolf: Schweizerische Militärpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die militärischen Beziehungen zu Frankreich vor dem Hintergrund der schweizerischen Aussen- und Wirtschaftspolitik 1914–1918, Berne 1976, pp. 126-131.

Selected Bibliography

- Bonjour, Félix: Souvenirs d'un journaliste, volume 2, Lausanne 1931: Payot.

- Fuhrer, Hans Rudolf: Die Oberstenaffäre, in: Fuhrer, Hans Rudolf / Strässle, Paul Meinrad (eds.): General Ulrich Wille. Vorbild den einen - Feindbild den anderen, Zurich 2003: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, pp. 359-408.

- Fuhrer, Hans Rudolf: Die Schweizer Armee im Ersten Weltkrieg. Bedrohung, Landesverteidigung und Landesbefestigung, Zurich 2003: Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

- Greter, Mirko: Sozialdemokratische Militärpolitik im Spannungsfeld von Vaterlandsliebe, Pazifismus und Klassenkampf. Der lange Weg der SPS hin zur Ablehnung der Landesverteidigung 1917, Berlin 2005: Pro Business.

- Schoch, Jürg: Die Oberstenaffäre. Eine innenpolitische Krise (1915/1916), Bern; Frankfurt a. M. 1972: Herbert Lang / Peter Lang.