Early Life↑

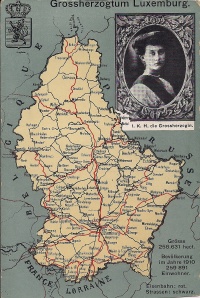

Marie Adelheid, Grand-Duchess of Luxembourg (1894-1924) was the eldest daughter of Wilhelm IV, Grand Duke of Luxembourg (1852-1912) and his wife Maria Anna of Braganza, Grand Duchess consort of Luxembourg (1861-1942). She ascended to the throne at the age of eighteen after her father's death. An idealist, Marie Adelheid had a strong personality and followed through on her convictions with uncompromising determination.

Her ideals were rooted both in her Catholic faith and in her belief that she had a God-given mission as Grand-Duchess. The Constitution of 1868 had given the head of the country extensive authority over state leadership, a power her predecessors had declined to use, so that Luxembourg was ruled de facto by a parliamentarian system. Marie Adelheid, however, did not consider her reign a representative duty. She interfered with the legislature and with the nomination of civil servants and members of government in an attempt to help the Catholic Church and the right-wing party and opposed the left-liberal party majority in Parliament. After she dissolved the Parliament at the end of 1915, an aggressive campaign for and against the crown followed, a conflict that considerably undermined her popularity. Through her “personal regime”, she had disregarded the Luxembourgers' democratic attitude. Instead of promoting domestic peace, she increased the tensions between political parties and split the population into two camps.

During World War I↑

World War I added to Marie Adelheid’s problems, especially as she descended from the German House of Nassau-Weilburg. On 2 August 1914, neutral Luxembourg was conquered by the German army, beginning four years of “amicable occupation.” During this period, government institutions continued to function, but were controlled by the German military. This created a difficult situation for the state, the crown, and the partly Francophile population that required a balancing act between neutrality and a sometimes voluntary and sometimes forced collaboration.

In the eyes of the Luxembourgian left and liberal public as well as the press of the Entente-powers, Marie Adelheid committed significant mistakes in her attitude towards the Germans. She cultivated tight family bonds to the German and Austrian princely families, spoke German, and her royal suite consisted almost entirely of German aristocrats, some of whom openly professed to support the occupying power. She even received the German commanding general, who had been the first to violate Luxembourg’s neutrality. On the advice of the Minister of State, Paul Eyschen (1841-1915), the German Emperor, who relocated his headquarters to Luxembourg in September 1914, was invited to dine at her castle. During the war, German kings, princes, high military brass and the Imperial Chancellor Georg von Hertling (1843-1919) socialised at court. In October 1917, Marie Adelheid became one of the godmothers of the German Crown Prince’s daughter. In 1918 her sisters Antonia, Princess of Luxembourg (1899–1954) and Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg (1896–1985) became engaged to Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (1869–1955) and Felix, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1893-1970), respectively, both of whom fought with the Central Powers in the war.

After the War↑

At the end of the war, Marie Adelheid’s political enemies accused her of having had close relations with Germany. The liberal and socialist newspaper started a defamatory campaign against her that emphasised that she was not a Luxembourger, but a foreign princess who did not understand the Luxembourgers' language or way of thinking and living. They further claimed that she had sympathised and collaborated with Germany, and was therefore a traitor to her country. Influenced by the fall of European royal families in the post-World War I period, liberals and socialists called for a republic.

Foreign policy concerns also forced Marie Adelheid to abdicate. The press in Allied countries accused Marie Adelheid of collaborating with the Germans. After the armistice in 1918, France and Belgium refused to send ambassadors to Luxembourg. Although the Luxembourg government supported her, they were therefore also forced to rescind their support.

Marie Adelheid saw herself as a patriot who had fought for Luxembourg’s independence. During the war she had spoken up for the suffering population as well as for the injured German and Allied soldiers, and in 1914 had played a large role in helping to found the Red Cross. Even her support for Luxembourgers who had been sentenced to death as spies by the occupation forces, and whose death penalty had been changed to lifelong jail thanks to her good relations to Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) could not save her.

In order to save the dynasty and independence of Luxembourg, Marie Adelheid abdicated on 9 January 1919. Resigned to the situation, she left the country without trying to justify herself. Her sister Charlotte succeeded her to the throne. During the referendum on 28 September 1919, the vast majority of the population voted to maintain the monarchy. As Grand-Duchess, Charlotte did not interfere in the domestic politics of the country and viewed her position as purely representative. When the German Armed Forces occupied Luxembourg for the second time on 10 May 1940, she went into exile and became a symbol of resistance against the Nazi dictatorship.

Josiane Weber, Luxembourg Literary Archives

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Collart, August: Sturm um Luxemburgs Thron, 1907-1920, Luxembourg 1959: Bourg-Bourger.

- Even, Pierre: Marie-Adélaïde. Großherzogin von Luxemburg, Herzogin zu Nassau: Dynastie Luxemburg-Nassau. Von den Grafen zu Nassau zu den Großherzögen von Luxemburg. Eine neunhundertjährige Herrschergeschichte in einhundert Biographien, Luxembourg 2000: Schortgen, pp. 261-279.

- Schoos, Jean: Marie Adelheid, in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 16, 1990, pp. 187-188.

- Trausch, Gilbert: La stratégie du faible. Le Luxembourg pendant la Première Guerre mondiale (1914-1919): Le rôle et la place des petits pays en Europe au XXe siecle (Small countries in Europe, their role and place in the XXth century), Baden-Baden; Brussels 2005: Nomos; Bruylant, pp. 45-176.

- Welter, Nikolaus: Im Dienste. Erinnerungen aus verworrener Zeit, Luxembourg 1926: St. Paulus-Druckerei.