Introduction↑

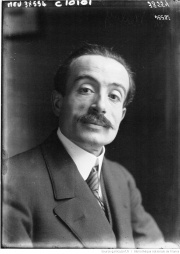

Louis-Jean Malvy (1875-1949) was born on 1 December 1875, the scion of a long-established political family from the Lot department that had staunchly opposed the monarchists and Bonapartists to establish the Republic. He was a member of the Radical Party and was elected deputy in 1906 on a markedly left-wing programme. He was Minister of the Interior when the war broke out in 1914, the second in command under Joseph Caillaux (1863-1944) and vice-president of the party.

During World War I↑

Responsible for ensuring that mobilization ran smoothly, he was immediately faced with the dilemma of whether or not to apply the “Carnet B”, a file with the names of 2,000-4,000 anarchists, unionists and revolutionary journalists who might pose a threat to the success of the operations. With the support of Council President René Viviani (1863-1925), he decided not to pursue preventive arrests and to instead trust the working class to build the Union sacrée. Minister of the Union sacrée, Malvy also sought to be the minister of social peace. He suspended the expulsion of religious orders and tried to contain social conflict so as not to disturb the nation’s defence. To do so, he relied on the General Confederation of Labour (Confédération générale du travail, or CGT) union, included its representatives on several committees and introduced a contract policy that raised the shackles of French employers. The Malvy approach was a savvy blend of flexibility and firmness, compromise and coercion, which sought to circumvent confrontation. During the labour strikes of May-June 1917, he recommended that Prefects contact the local Trade Union Councils rather than resort to force, which would encourage disorder. He took a similar approach to pacifist circles. He tolerated pacifist activity so as not to jeopardize his partnership with Léon Jouhaux (1879-1954), head of the CGT union, and put pacifist activists under surveillance rather than have them arrested.

Social Unrest↑

When a wave of lassitude overtook the country in 1917, with mutineers at the front, strikes behind the lines and a swell in pacifism, Malvy found himself in the dock. The most virulent attacks came from Action Française, which accused the minister of being a traitor working for Germany, of instigating disorder in order to impose the solution of Caillaux as President of the Council - the man who was prepared to accept a compromise peace with Germany. A press campaign by the extreme right wing presented him as a thief, alcoholic, cocaine addict, libertine, rapist and syphilitic. Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) decided to seize on the atmosphere of scandal and great accusation to prey on this weakened player on the governmental stage in order to topple the cabinet and hoist himself to the Council presidency, which is exactly what happened in November 1917. To block all alternatives, Clemenceau had his rival Joseph Caillaux locked up. Malvy, who wanted to be cleared of the accusations of treason spread about him by the right, was brought before the Senate, which sat as a high court of justice. Not wishing to challenge the authority of Clemenceau, the Senators sentenced him to five years of banishment in August 1918, at the end of a political trial.

After the War↑

Although re-elected deputy in 1924 and re-made minister, Louis-Jean Malvy was never able to shake his reputation as a traitor. His crime was simply to have initiated a policy of social compromise - which, in a civil war country like France, is no trifling matter.

Jean-Yves Le Naour, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Translator: Jocelyne Serveau