Introduction↑

“Aerial combats certainly are exciting and soon over. They try one’s nerves to the limit but there is very little if any time to think of danger to one’s self,” stressed pilot Edmond C. C. Genêt (1896-1917).[1] His words define the essence of the Lafayette Escadrille (LE). They were a cadre of courageous daredevils. Thirty-eight Americans flew for the LE (five additional members were French), and eleven would not survive the war.[2] The men who enlisted with the French risked losing American citizenship, but they wanted to partake in the “great adventure” and join what they felt was a just cause. The sky above the Western Front, however, proved dire: 75 percent of the war’s pilots did not survive more than nine months.[3]

Formation↑

Before the United States entered the war in 1917, Americans sympathetic to France’s cause joined the French Foreign Legion. The idea of a squadron comprised of American volunteers began with American aviation pioneer Norman Prince (1887-1916). In January 1915, Prince proposed that American pilots join the Aéronautique Militaire (French Air Service (AM)). It was not until one of the founders of the American Ambulance Corps, Dr. Edmund L. Gros (1869-1942), and an undersecretary of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jarousse de Sillac (1873-1934) became involved that the LE took shape.

Sillac scheduled a meeting for Gros with the Chief of French Military Aeronautics, Lieutenant General Auguste Hirschauer (1857-1943), who realized that an American squadron serving France would provide invaluable propaganda and garner active assistance for the Allies. Hirschauer authorized the Escadrille N.124 (N designating Nieuport 11, the aircraft first used by the squadron), named Escadrille Américaine, which began operation on 20 April 1916. In December, the German ambassador to the United States, Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff (1862-1939), took issue with the name since America was neutral. The French, complying with Gros’s request, renamed the squadron the Escadrille des Volontaires and then the Escadrille de Lafayette (Lafayette Escadrille). Six weeks after the LE’s creation, the squadron’s popularity required France to establish the Franco-American Flying Corps (later renamed the Lafayette Flying Corps (LFC)) to enable additional Americans to fly for the AM. The LE was not the LFC. The latter represented the 269 American volunteers who served in the French Air Service during the war; the LE was a squadron made of LFC members.[4]

Performance↑

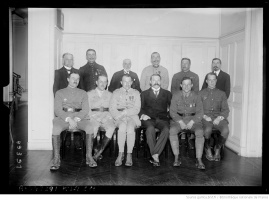

The LE’s first patrol occurred on 13 May 1916. Daring and resourceful, the American pilots, initially commanded by Captain Georges Thénault (1887-1948) and Lieutenant Alfred de Laage de Meux (1891-1917), undertook reckless individual air attacks rather than engage in coordinated formation tactics. Sustaining brutal injuries one day and demanding to fly the next, the French officers found the Americans aggressive and rash. The fame of the LE grew when they served at Verdun, flying two patrols each day. The Americans conducted search and destroy missions, attacked German observation balloons, and guarded French reconnaissance planes. In the air over Verdun from May-September 1916, the Americans flew 1,000 sorties, 146 combat engagements, and achieved thirteen victories.[5] Raoul Lufbery (1885-1918) became top ace of the squadron. During 1917, the LE hardened into a cohesive force with low-altitude reconnaissance missions and combat operations. When the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service formed in January 1918, the LE disbanded on 18 February and most pilots joined the new 103rd Aero Squadron.

Conclusion↑

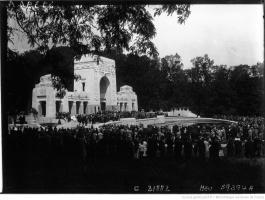

Despite modest statistical achievements, the LE inspired other Americans to become pilots and aided in bringing air warfare to the attention of the United States. In addition, the tremendous amount of press coverage given to their exploits provided a valuable propaganda asset for the French. The LE’s legacy speaks to the impact the men made during the war. In 1928, the French government, bolstered by private funding, built the Lafayette Escadrille Memorial to honor all LFC pilots in Marnes-la-Coquette, France. LE commander Georges Thénault chose to be buried with his men at the memorial. By 1931, over 4,000 imposters claimed they flew for the LE.[6] Thousands of Americans craved inclusion with the nation’s first air combat unit pioneers, but only thirty-eight men deserve that distinction. When reflecting on his war experience, Thénault concluded, “It will be the honour of my life to have commanded them.”[7]

Edward A. Gutiérrez, Northeastern University

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ Genêt, Edmond C. C.: Diary entry from 15 February 1917, in: Brown, Walt Jr. (ed.): An American for Lafayette. The Diaries of E. C. C. Genet, Charlottesville 1981, p. 147.

- ↑ Ruffin, Steven A.: The Lafayette Escadrille. A Photo History of the First American Fighter Squadron, Philadelphia 2016, pp. 180-182; Mason, Herbert Molloy Jr.: The Lafayette Escadrille, New York 1964, pp. 298-299.

- ↑ Morrow, John H. Jr. / Rogers, Earl (eds.): A Yankee Ace in the RAF. The World War I Letters of Captain Bogart Rogers, Lawrence 1996, p. 10.

- ↑ Ruffin, Lafayette Escadrille 2016, pp. xii-xiii. See also Hall, James Norman / Nordhoff, Charles Bernard (eds.): The Lafayette Flying Corps, volume 2, Boston 1920, pp. 324-327.

- ↑ Flammer, Philip M.: The Vivid Air. The Lafayette Escadrille, Athens 1981, p. 80.

- ↑ Mason, Lafayette Escadrille 1964, p. 287.

- ↑ Thénault, Georges: The Story of the Lafayette Escadrille, Boston 1921, p. 169.

Selected Bibliography

- Flammer, Philip M.: The vivid air. The Lafayette Escadrille, Athens 1981: The University of Georgia Press.

- Mason, Herbert Molloy Jr.: The Lafayette Escadrille, New York 1964: Random House.

- Murphy, T. B.: Kiffin Rockwell, the Lafayette Escadrille and the birth of the United States Air Force, Jefferson 2016: McFarland & Company.

- Ruffin, Steven A.: The Lafayette Escadrille. A photo history of the first American fighter squadron, Philadelphia 2016: Casemate.

- Thénault, Georges: The story of the Lafayette Escadrille, Boston 1921: Small, Maynard & Co..