Kun’s Life until the End of the First World War↑

Béla Kun (1886-1938?) was born in a Transylvanian village, in what is now Romania. His family belonged to the stratum of Jewish bourgeoisie who had assimilated into the Hungarian population; his father was district notary. He stayed in Transylvania to pursue his studies. In 1902 he became a member of the Social Democratic Party of Hungary. At the beginning of the 20th century, he played an important role in the Transylvanian social democratic workers’ movement.

Kun joined the army in 1914 and fought with the 21st Infantry Regiment of Kolozsvár of the Hungarian Territorial Army. His unit fought against Russian forces in the Carpathians and Galicia. Kun was promoted to ensign on 1 November 1915. His letter published in the 28 November 1915 issue of Népszava (People’s Voice), the main periodical of the Social Democratic Party of Hungary, indicated that his political views had not changed; he remained faithful to social democratic ideas. He wrote: “What we obtain here—the experience, the merit and the recognition—are struggles fought in times of peace. Let it all belong to Népszava and those ideals that, in times like this, are voiced only by Népszava.”[1] In January 1916, when his regiment was reorganised, Kun became the commander of a mortar unit. That summer, he was captured by the Russians. Later the same year, an official notice was published that he had been awarded the Silver Gallantry Medal, 1st Class.

The Russians sent Kun to the prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in Tomsk, where he sought company among officers with similar left-wing views and propagated social democratic ideals. In the revolutionary weeks of 1917, Kun managed to leave the POW camp. He joined the Bolsheviks that year, before they came to power in the autumn. At the turn of 1917/18 he travelled to Petrograd, and in March he became president of the Hungarian Group of the Communist (Bolshevik) Party of Russia. Later he came to be leader of the federation of foreign (mainly POW) groups. He also took part in the armed conflicts to protect the new power, such as building up the Uralian front in 1918.

Kun’s activities did not have a significant impact upon the course of the First World War. The war, however, did play a determining role in his life: during his captivity as a POW he encountered Bolshevism and was inspired to join its ranks, operating as a communist politician for the decades that followed. In preparation for their return home to Hungary, Kun and his comrades formed the Communist Party of Hungary on 4 November 1918 in Moscow. Kun became one of the leaders of the party.

Kun’s Activities after the First World War↑

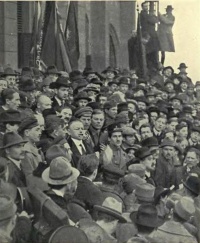

Kun and his compatriots arrived in Budapest in mid-November 1918. Thanks to Kun’s organisational work, the Communist Party of Hungary was established in the homeland by the second half of November. In spring 1919 the Hungarian democratic regime was in crisis, struggling with numerous external and internal political problems. Hungary belonged to the losing side in the First World War, making their international situation tenuous. The victorious Allies supported the Romanian, Czech, and Serbian territorial claims against Hungary. Romanian, Czech, and Serbian troops therefore occupied large areas of Hungary at the end of 1918 and beginning of 1919.

The Hungarian president of the republic, Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955), was convinced that the Hungarian political leadership would not be able to mount a successful resistance to such forces. So instead, he planned to resist with the support of external left-wing political forces, and then appoint a new, social democratic government to garner domestic support. But the social democrats did not want to form a cabinet alone in such a grave political situation. Without Károlyi’s knowledge, they made an agreement with the communists to assume power jointly. This dictatorship of the proletariat, called the Soviet Republic of Hungary (Magyarországi Tanácsköztársaság), took power on 21 March 1919 and remained in power until 1 August 1919.

Throughout this period, Kun was commissar for foreign affairs. Between 3 April and 24 June, he was appointed commissar of military affairs, and on 24 June he became the deputy commander in chief of the army. Although Kun was not the head of the government, he was still seen as the true leader of the Soviet Republic of Hungary, having more authority and power than anyone else. According to his biographer, György Borsányi (1931–1997), he was the only Hungarian communist with charisma. [2] Kun’s ability to choose the right secretaries, bodyguards, and informants strengthened his position. However, he did not wield personal authoritarian power. There were real and open debates within the dictatorship’s leadership; the unification of social democrats and communists did not put an end to the conflicts that had existed both between the parties and within each party. Kun undertook the role of mediator in this situation, and more than once, he took the side of the social democrats. It was not a dictatorship of Béla Kun, but a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Kun followed the Russian Bolshevik pattern in his political conceptions, although his was a milder, more European, and social democratic version in many ways. For instance, faithful to social democratic ideas, Kun refused the land distribution to the peasants, even if such action would tighten the social base of the dictatorship. Following the commencement of the attacks against the Soviet Republic of Hungary by the Romanians and the Czechs in April 1919, he dealt much with military affairs. However, the leaders of the dictatorship could solve neither the external nor internal problems of the Soviet Republic. Because of internal circumstances, it became clear in early summer that the dictatorial regime had no hope of defeating its enemies. The government resigned on 1 August 1919. Alongside many other leading figures, Kun left for Austria.

Kun was interned by the Austrian government for almost a year with his followers. (He lived in various places, including Karlstein.) Upon his release, he made his way to Soviet Russia. He filled leading positions in the Communist International (Comintern) in the decades that followed. He also participated in the reorganisation of the Communist Party of Hungary, for which he travelled to Austria on several occasions in the 1920s. At the end of the 1930s he fell victim to Joseph Stalin’s (1878-1953) Great Terror.

Kun’s life was by no means unique in the workers’ movement of the time: at the beginning of his career he was a social democrat; he became a POW of the Russians during the First World War; he joined the Bolsheviks in Russia; and he became an important figure in the international communist movement—only in the end to be purged by Stalin’s Terror.

Boldizsár Vörös, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Borsányi, György: The life of a communist revolutionary, Béla Kun, New York 1993: Columbia University Press.

- Chase, William J.: Microhistory and mass repression. Politics, personalities, and revenge in the fall of Béla Kun, in: Russian Review 67/3, 2008, pp. 454-483.

- Dorokhin, V. D.: Novye dannye o gibeli Bely Kuna (New data on the death of Béla Kun), in: Voprosy Istorii KPSS 3, 1989, pp. 34-35.

- Kun, Béla: Revolutionary essays (Reprinted from Pravda), London 1977: Slienger.