Soldier and Statesman↑

Early Career↑

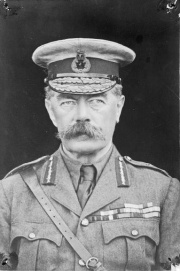

Born near Listowel in County Kerry, Ireland, Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) passed out of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in December 1870 before being commissioned into the Royal Engineers. Much of his early career was spent in the Middle East and Egypt. Having become Sirdar (Commander-in-Chief) of the Egyptian army in 1892, he led it in the re-conquest of the Sudan and the defeat of the Khalifa at Omdurman in 1898. The following year, he was sent to South Africa as Chief of Staff to Field-Marshal Lord Frederick Sleigh Roberts (1832-1914), succeeding the latter as Commander-in-Chief in November 1900. His policy of attrition – based upon lines of blockhouses from which drives by mounted columns were launched – eventually wore down Boer resistance. In introducing concentration camps for civilians, he aroused widespread criticism, but he played a conciliatory role in the 1902 peace settlement. Then, as Commander-in-Chief, India, from 1902 to 1909, Kitchener instituted overdue reforms in the Indian army, modernising training and organising standardised divisions to deal with external threats rather than internal unrest. Promoted to Field-Marshal in 1909 and granted an earldom in 1914, he was serving as British Agent and Consul General in Egypt, but home on leave, when Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914.

Secretary of State for War↑

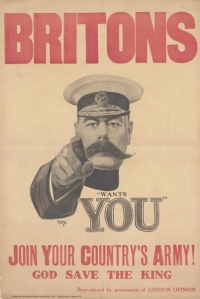

The next day, on 5 August, a reluctant Kitchener was persuaded by Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) to accept the post of Secretary of State for War. Asquith himself had reservations, regarding the appointment as a “hazardous experiment”, but Kitchener’s move to the War Office was greeted with enormous enthusiasm by the general public.

Expanding the Army↑

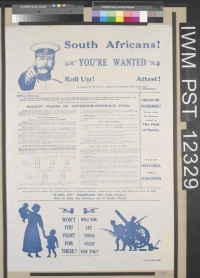

Kitchener, like Douglas Haig (1861-1928), was almost alone among Britain’s leading soldiers and statesmen in predicting that the war would be costly and protracted and that millions of men would be required to achieve victory. He estimated that the conflict would last at least three years and that Britain’s full military strength could not be deployed until 1917. At that point, with other powers nearing exhaustion, the British army would be able to exert an increasingly weighty influence on the course of operations at the decisive stage of the war. To this end, beginning with a relatively modest appeal for 100,000 men as early as 7 August, Kitchener immediately set about raising a series of “New Armies” – each duplicating the six infantry divisions of the original British Expeditionary Force (BEF) – as well as allowing the Territorial Force (TF) to expand and undertake active service overseas. While this process was sometimes haphazard and badly regulated – for example, in permitting the unrestricted recruiting of skilled workers – 2,466,719 men had voluntarily enlisted by the end of 1915, enabling Britain eventually to field over seventy divisions.[1] It was in creating a mass army and providing the vital initial impetus for the mobilisation of national and Imperial resources that Kitchener made his greatest contribution to Britain’s war effort.

Kitchener and Munitions↑

In the absence of a blueprint for a corresponding mobilisation of industry, as only a short war had been expected, and given the indiscriminate enlistment of skilled workers, it inevitably took time for British firms to adapt to the colossal new demands for munitions, though Kitchener’s desire to keep control of production firmly in the hands of the War Office did not help matters. Even though the supply problem exposed in the Shells crisis of May 1915 owed more to a lack of proper pre-war planning than current War Office deficiencies, Kitchener was heavily criticised for the shortages suffered by the British forces in France and Belgium. With the formal establishment of a separate Ministry of Munitions, under David Lloyd George (1863-1945), in June 1915, the War Office lost most of its powers in this sphere apart from fixing the army’s needs in munitions and supervising their distribution. However, Kitchener had done much to lay the foundations of the massive expansion of British armaments production for which Lloyd George, somewhat unjustly, later claimed most of the credit. Kitchener’s achievements in this area are perhaps more fairly judged by the greatly improved situation at the end of 1915 than by the shortages in May.

Kitchener’s Strategic Views↑

As Secretary of State for War, Kitchener did not initiate any fundamental change in British strategy. He inherited the commitment to fight alongside the French on the continent, but nevertheless maintained a strong belief in the primacy of the Western Front. Until his “New Armies” were complete and fully trained, he favoured a policy of “active defence”, whereby small-scale attacks would be delivered on tactically-important points, forcing the Germans to incur severe casualties in attempts to regain the lost ground. On the other hand, he recognised the realities of coalition warfare and, to relieve pressure on Russia after setbacks on the Eastern Front, he sanctioned the British offensive at Loos in France in September 1915. Moreover, the continuing stalemate on the Western Front persuaded him to acquiesce in alternative strategic ventures such as the Dardanelles campaign, but, in the latter case, he displayed irresolution throughout and never really provided the British and Dominion forces involved with appropriate resources in men and materiél. Having belatedly seen the situation for himself in November 1915, he felt compelled to recommend the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula.

Declining Authority↑

Kitchener initially dominated the Cabinet, but he was uncomfortable in political debates and distrusted politicians, signs of mutual disenchantment soon becoming evident. Long accustomed to making his own decisions, he resented interference and was loath to delegate, making insufficient use of bodies such as the Army Council and General Staff, which could have eased his increasingly crushing, and partly self-inflicted, workload. As voluntary recruiting figures fell, casualties mounted and the manpower question became more urgent during 1915, he failed to provide a clear lead on the issue of conscription. In December 1915, following military reverses in France and the Dardanelles, Lieutenant-General Sir William Robertson (1860-1933) was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), it being stipulated that he (Robertson) would henceforth be the Cabinet’s principal advisor on military operations. While he worked well with Robertson and remained popular with the public, Kitchener’s authority was essentially limited to matters of recruiting, supply and administration.

Death and Legacy↑

Kitchener drowned on 5 June 1916 when HMS Hampshire, carrying him on a mission to Russia, struck a mine and sank off the Orkneys. For all his shortcomings, Kitchener had created a mass army which was not only capable of fighting a major continental war, but which also – just as Kitchener had envisaged – played a key part in the ultimate Allied victory.

Peter Simkins, University of Wolverhampton

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

- ↑ His Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO): Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London 1922, p. 364. The figure relating to the number of divisions raised has been compiled from the details given in Becke, Major A.F.: Order of Battle of Divisions, Parts 1-4, London 1935-1945.

Selected Bibliography

- Arthur, Sir George: Life of Lord Kitchener, 3 volumes, London 1920: Macmillan.

- Cassar, George H.: Kitchener. Architect of victory, London 1977: Kimber.

- Cassar, George H.: Kitchener's war. British strategy from 1914 to 1916, Washington, D.C. 2004: Brassey's.

- French, David: British strategy and war aims, 1914-1916, London; Boston 1986: Allen & Unwin.

- Simkins, Peter: Kitchener's army. The raising of the new armies, 1914-1916, Manchester; New York 1988: Manchester University Press.