Origins↑

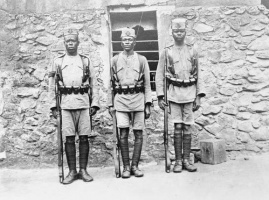

Originally consolidated from the Central African Rifles, the Uganda Rifles, and the East African Rifles in 1902, the unit was composed of locally-recruited African rank-and-file soldiers led by white officers. These African soldiers took the title of askari after the locally used Kiswahili word for guard or soldier. These forces fought against local slaving efforts in Central Africa, the Ugandan kingdoms, the Nandi in British East Africa, and the anti-colonial struggles of the Somali Mullah Sayyīd Muhammad `Abd Allāh al-Hasan (1856–1920). At their largest during the pre-war years the KAR could claim six battalions. By the beginning of the First World War, the forces had been reduced to three territorially-aligned units. The 1st KAR were recruited and based in the Nyasaland colony, the 3rd KAR were aligned with British East Africa (BEA), and the 4th KAR was composed of Ugandan troops and based in that territory. At the outbreak of war even these units had been reduced to a total of sixty-two British officers, two British NCOs, and 2,319 African non-commissioned officers and enlisted men.[1]

1914-1915: Strategic Defensive↑

The commencement of hostilities found the KAR scattered across their various colonial territories, with various detachments as far afield as Zanzibar and the extreme Northeast of Nyasaland. Despite the effectiveness of a detachment of the 3rd King’s African Rifles in defeating a German raid aimed at Mombasa in September, the African soldiers were not well thought of by the British officers of the newly-arrived Indian Expeditionary Force. As such, the King’s African Rifles did not take part in the initial offensive action against German East Africa at the disastrous Battle of Tanga. The crushing defeat of the Indian Army forces led to the British being thrown on the strategic defensive. Due to the weakness of the British forces, the King’s African Rifles were deployed primarily to defend the vital Uganda Railway. In early 1915, given the inability to raise significant reinforcements from the British or Indian Armies, the military leadership in East Africa raised the possibility of expanding the King’s African Rifles.[2] However, permission for this was denied for reasons including paucity of language-proficient officers and inadequate supply of African recruits from designated "martial races".

Despite the lack of major offensive action against German East Africa, the King’s African Rifles did see action during 1915. The Battle of Mbuyuni in July of 1915 saw elements of the 1st and 4th KAR playing a decisive role in driving German raiding parties back from their advanced positions near Salaita, while the Battle of Longido West included soldiers of the 3rd KAR taking part in halting further German raiding aimed at the Uganda Railway. However, just as often the King’s African Rifles were ignored by the British field commanders, such as at the Battle of Bukoba. While three companies of the 3rd KAR were used to secure the bridgehead needed for attacking the town, they were held outside the town and simply witnessed its looting by the 25th Royal Fusiliers, an all-white British unit called the “Legion of Frontiersmen.”[3]

1916: Secondary Forces↑

The arrival of General Jan Smuts (1870-1950) and 20,000 South African soldiers at the beginning of 1916 marked a turning point in the campaign. While Smuts re-raised the previously defunct 2nd and 5th King’s African Rifles, the East African soldiers were still seen as secondary forces within the East African theatre.[4] Smuts’ plan called for a major drive southwards from British East Africa as well as several smaller advances into German East Africa from the West and South. The central offensive saw the KAR suffering the heaviest casualties at the Battle of Latema Nek, including the death of the commander of the 3rd KAR. Meanwhile the 1st and 4th King’s African Rifles were entering the fray, with the 4th being part of the Lakes Force that advanced to Mwanza and towards Tabora in July, while the 1st was part of the Nyasaland and Rhodesia Field Force that clashed with the enemy column commanded by Major-General Kurt Wahle (1855-1928) in May. Still, these smaller forces were considered sideshows by the British leadership and Smuts’ advance was interpreted as an achievement of South African arms. By the end of the year, the British forces had pressed the German forces south of the Rufiji River.

1917: Expansion and Offensive↑

At the end of 1916, Smuts was called away to serve as a member of the Imperial War Cabinet and over 12,000 of the recent reinforcements needed to be evacuated due to ill health. Smuts’ successor, Major-General Reginald Hoskins (1871-1940), recognized the need for replacement troops and rapidly expanded the King’s African Rifles to replace the withdrawing white South African, Rhodesian, and British soldiers. By February of 1917, the KAR had expanded from six battalions to twenty through a period of intensive recruiting campaigns within Britain’s East African colonies. These reinforcements also included a new 6th Regiment, which was composed of ex-German askari who had been captured by the British or discharged by the retreating Schutztruppe and who volunteered for continued military service. The expansion had seen the KAR grow from the 8,159 that Smuts had employed to 23,325 by July 1917.[5]

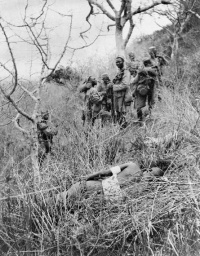

From this point on, the King’s African Rifles would bear the brunt of the fighting in the East African campaign. Forces of mostly KAR soldiers pressed out from the ports of Lindi and Kilwa and threatened the eastern flank of Major-General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck’s (1870-1964) forces as he withdrew from the advance of General Jacob Louis van Deventer (1874-1922). In the meantime a column of German troops set out across the colony in February, raiding for food, water, and ammunition. The 6th King’s African Rifles, with limited help, brought the column to heel in October.[6] When von Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces finally brought to battle at the southern edge of German East Africa, it would be the King’s African Rifles that would form the majority of the troops at the hard-fought battles of Narumgombe and Mahiwa. Following these battles, von Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces slipped across the Rovuma River, extending the campaign into another year.

1918: Endgame and Demobilization↑

By the beginning of 1918, the King’s African Rifles were the majority of the forces that pursued the German troops across Mozambique and beyond. Although the majority of 1918 would be spent chasing the elusive Germans, the KAR would fight sharp engagements at Kireka Mountain, Korewa, Namirrue, and Kasama. Although none of these would halt the German maneuvering, when given the chance such as at Korewa, the KAR managed to acquit themselves well against their longtime foes. In the end, though, it was not the KAR which stopped the Schutztruppe, but the Armistice, news of which reached von Lettow-Vorbeck on 13 November leading to his ultimate surrender on 25 November.

Despite the experience gained in the campaign and the continued specter of local unrest, the KAR formations that had been raised were rapidly demobilized. Although there were complaints among the governors of the colonies, who felt that maintaining a substantial force would be worthwhile, the KAR was reduced to ten battalions in 1919 over concerns of cost and fear of armed Africans. Despite initially being ignored in the British strategy in East Africa, ultimately the KAR had grown to over 30,000 troops by 1918, and 4,237 askari and 177 Europeans died within the KAR ranks while bringing the campaign to a conclusion.

Charles Thomas, United States Military Academy Westpoint

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Moyse-Bartlett, Hubert: King’s African Rifles, Uckfield 2004, p. 701.

- ↑ Hordern, Charles: History of the Great War. Military operations East Africa. Vol. I - August 1914 - September 1916, Nashville; London 1990, p. 132.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004, p. 116.

- ↑ Dolbey, Robert Valentine: Sketches of the East African campaign, London 1918, p. 9.

- ↑ Moyse-Bartlett, King’s African Rifles 2004, p. 701.

- ↑ Orr, G. M.: A remarkable raid. East Africa 1917, in: Journal of the United Services Institute LXXI (1926), p. 75.

Selected Bibliography

- Dolbey, Robert Valentine: Sketches of the East Africa campaign, London 1918: J. Murray.

- Hordern, Charles / Stacke, H. Fitz M.: Military operations East Africa, August 1914-September 1916, volume 1, Nashville; London 1941: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Moyse-Bartlett, H.: The King's African Rifles. A study in the military history of East and Central Africa, 1890-1945, Aldershot 1956: Gale & Polden.

- Orr, G. M.: A remarkable raid, in: Royal United Services Institution 71/481, 1926, pp. 73-80.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.