Introduction↑

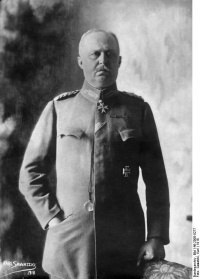

The Prussian War Minister, Adolf Wild von Hohenborn (1860-1925) initiated the Judenzählung on 11 October 1916. The Judenzählung was a response to the demands of the anti-Semitic circles in the army and the Reichstag who accused Jews of deliberately evading front-line military service. As a result, the War Ministry authorized a statistical census to determine how many Jewish soldiers were serving at the forward lines relative to those employed behind the front in non-combat support roles.

The relevant passage of the order states:

According to Hohenborn’s directive, the purpose of the census was “to investigate these complaints and, should they prove unwarranted, to be able to refute them.”[2] It required the commanding officer of each regiment to complete a questionnaire tallying the precise number of officers, medical personnel, and enlisted men of Jewish faith stationed at the front. It also asked for the number of Jews killed in action, how many had been decorated for bravery, and how many were serving in rear-echelon postings despite being “fit” for frontline service.

Reasons for the Judenzählung↑

The War Ministry’s decision to launch an official inquiry into claims of Jewish shirking should be viewed against the backdrop of the Hindenburg Program, which called for a sweeping, top-down reassessment of all rear-area garrisons and civilian industries in an effort to systematically exploit the home front and superfluous logistics units for much needed manpower at the front. The measure marked the official collapse of Burgfrieden, for it contradicted and violated the principle of equality among all parties and confessions proclaimed by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) during his landmark speech before members of the Reichstag on 4 August 1914.

Tapping into long-held anti-Semitic prejudices that equated Jews with physical inferiority, a lack of patriotism, and an unwillingness to self-sacrifice for the Fatherland, the census exploited these stereotypes and transformed them into a political weapon. Although Jewish soldiers had been confronted with these stereotypes prior to World War I and before the implementation of the Jew Count, the difference between daily confrontations with anti-Semitism and the Judenzählung is that the census represented an officially sanctioned, state measure. The stereotype of the Jewish Drückeberger (shirker) was elevated from the private realm to the public political arena in a calculated effort to undermine Jewish claims for equality and social acceptance after having risked their lives on the battlefield.

The census was not the work of a single anti-Semitic actor, but arguably represented the intentions of a much broader segment of the German conservative-nationalist milieu. Several months before Hohenborn’s order, the far-right Reichstag deputy Ferdinand Werner (1876-1961) had already called for such a measure, as well as several high-ranking officers in the German military, most notably the headquarters of the II. Army Corps in Stettin, which had received anonymous complaints that Jewish conscripts were serving out the war in administrative and clerical postings far removed from the actual fighting. Although the War Ministry justified the census on the grounds that it was intended to refute such allegations and lay to rest unfounded claims of Jewish shirking, evidence points to the contrary, suggesting that the underlying intent of the Judenzählung was in fact to deliver proof that Jews had deliberately and collectively forfeited their military obligations to the Fatherland in time of crisis.

Flaws in the Census↑

As a statistical census, the Judenzählung was inherently flawed. It did not take into account the large number of Jewish soldiers temporarily absent from their units, due to leave, transfers, or injury. There were also unconfirmed reports that several commanders deliberately removed Jews from the front line before completing the questionnaires. Although the statistics compiled by the War Ministry in November 1916 failed to uncover any evidence of Jewish wrongdoing, the Ministry kept the census results classified.[3] The only acknowledgement that the Jews had been exonerated from the initial allegations came in a letter dated 20 January 1917 from General Hermann von Stein (1854-1927), Hohenborn’s successor in the War Ministry, to Reichstag deputy Oskar Cassel (1849-1923), which conceded that any charges leveled against the Jewish war record were unfounded. This meek acknowledgement drew little public attention and was insufficient to silence the controversy that contentious and divisive debates in the Reichstag ignited and that had generated considerable attention in the right-wing press.

Conclusion: Effects of the Census↑

The Judenzählung was a serious blow to Jewish morale during the war. News of the census provoked intense debates among Jewish intellectuals, activists, and local community leaders on the home front, and received considerable scrutiny in the Jewish press. Jewish soldiers also saw the census as a grave injustice, yet the outrage tended to subside more quickly at the front, either because it was regarded as another example of harassment by the officers’ corps, or because of the exigencies of the wartime military situation. In many cases, Jewish soldiers did not learn about the census until after the war. In general, Jewish soldiers showed few signs of long-term demoralization, nor did the census diminish their resolve to fight for Germany during the last two years of the conflict.

The implications of the Judenzählung would be far more egregious after the war. Because the census results were never disclosed to the German public, the mere fact that it had been carried out legitimized and reinforced the anti-Semitic stereotypes that the political right propagated after 1918, fueling speculation and wild rumors about the Jewish war record. In the years that followed, Jews were thrust into the unenviable position of having to prove their war record. Jewish organizations such as the Centralverein (CV) and Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (RjF), expended enormous resources and energy to fend off accusations of cowardice and dereliction of duty with statistics on the number of Jewish war dead, which activists and local communities across Germany had painstakingly compiled.

Yet the fog of ambiguity hanging over the Jewish war record remained unresolved, feeding suspicions of Jewish disloyalty and indifference to the Fatherland that were seared into public memory. The assertion that Jews had collectively sought refuge in comfortable postings behind the lines while “real” Germans had died facing the enemy formed a core element of the Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back myth), which held that a conspiracy of socialists and Jews on the home front had undermined the fighting power of the German army. The Judenzählung gave these claims a veneer of credibility. It was a catalyst for the fundamental shift that occurred after 1918 as anti-Semitism and debates on the “Jewish Question” were no longer restricted to the radical fringe of the nationalist right, as had been the case before the war, but would reach into all strata of German society, including groups and individuals that had previously shunned any association with anti-Semitism. Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and the NSDAP would later appropriate and exploit the myth of Jewish treachery during World War I and the Dolchstoßlegende would become a central tenet of Nationalist Socialist discourse on the Jewish Question.

Michael Geheran, Clark University

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Notes

- ↑ Order from Adolf Wild von Hohenborn on 11 October 1916, Kriegsministerium: Abteilung für allgemeine Armeeangelegenheiten, Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart, M 1/4, Bü 1271.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The relevant documents pertaining to the Judenzählung are preserved at the Hauptstaatsarchiv-Stuttgart in the files of the Württemberg War Ministry: “Nachweisung der beim Heere befindlichen (einschl. der noch vorhandenen vertraglich angenommenen Ärzte) wehrpflichtigen Juden,” 11 October 1916, Kriegsministerium: Abteilung für allgemeine Armeeangelegenheiten, HStAS, M 1/4, Bü 1271; and “Maßnahmen gegen angebliche “Drückeberger” unter der wehrpflichtigen jüdischen Bevölkerung im 1. Weltkrieg,” Sammlung zur Militärgeschichte, HStAS, M 738, Bü 46.

Selected Bibliography

- Angress, Werner T.: The German army's 'Judenzählung' of 1916. Genesis-consequences-significance, in: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 23, 1978, pp. 117-137.

- Grady, Tim: The German-Jewish soldiers of the First World War in history and memory, Liverpool 2011: Liverpool University Press.

- Grünwald, Michael: Antisemitismus im Deutschen Heer und Judenzählung, in: Berger, Michael / Römer-Hillebrecht, Gideon (eds.): Jüdische Soldaten, Jüdischer Widerstand in Deutschland und Frankreich, Paderborn 2012: Ferdinand Schöningh.

- Heikaus, Ulrike / Köhne, Julia (eds.): Krieg! Juden zwischen den Fronten, 1914-1918, Berlin 2014: Hentrich & Hentrich Verlag.

- Krumeich, Gerd: Aux origines de l’antisémitisme nazi. Compter les Juifs pendant la Grande Guerre, in: Revue d’histoire de la Shoah 189, 2008, pp. 359-372.

- Penslar, Derek Jonathan: Jews and the military. A history, Princeton 2013: Princeton University Press.

- Rosenthal, Jacob: 'Die Ehre des jüdischen Soldaten'. Die Judenzählung im Ersten Weltkrieg und ihre Folgen, Frankfurt a. M. 2007: Campus.

- Zechlin, Egmont: Die deutsche Politik und die Juden im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 1969: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.