Introduction↑

Parliamentary government in New Zealand was in many respects stable during the war, but the circumstances of wartime politics arguably accelerated a political realignment that was underway in any case: the rise of a significant Labour party and the resulting merger of non-Labour forces into one party of moderate conservatism.

The Shaping of New Zealand’s Parliament up until 1914↑

New Zealand was one of the earlier jurisdictions to complete the introduction of formal democracy. The islands were incorporated into the British Empire in 1840; internal self-government was conceded to the white settlers in the mid-1850s and a steady expansion of the franchise saw the abolition of plural votes for men of property in 1889 and universal suffrage in 1893. Women, however, were ineligible for election to parliament until 1919. All indigenous Māori men had had the vote since 1867, and Māori women were included in universal suffrage in 1893, but most Māori were compelled to vote in separate Māori electoral districts drawn with little regard for population, and were denied the secret ballot until 1938. An impartial Representation Commission Electorate defined boundaries, but a "country quota", usually justified by the size and remoteness of rural electorates, allowed them up to 28 percent less population than other electorates.[1]

In the early 1890s, the supremacy of the popularly elected House of Representatives was confirmed when London ordered the vice-regal governor to act on the advice of ministers, so long as the latter demonstrably held the confidence of the House. This resolved a dispute over the composition of the upper house, when a reforming Liberal government sought to make additional appointments to the Council, and to replace lifetime tenure with renewable seven-year terms.[2] Thereafter, the Council’s influence diminished; it was occasionally convenient for a government to appoint a candidate for ministerial office to the Council, but otherwise it was increasingly a place where politicians could enjoy a dignified retirement.

In 1907 New Zealand’s formal designation became that of the Dominion of New Zealand. Parliament remained fully autonomous over internal affairs but in the last resort London commanded foreign and defence policy. "In 1914...Britain’s declaration of war applied automatically to the Dominions, but they made their own decisions about military contributions."[3]

Until 1890, while one could identify "liberal" and "conservative" impulses, parties had been at best embryonic, with local loyalties and the imperatives of infrastructure usually at least as important as ideology. The 1890 general election returned a government that proclaimed its identity as Liberal and which was based on a coalition of classes – most importantly, a newly assertive labour movement on the one hand, and smaller farmers, aspiring farmers, and smaller commercial enterprise on the other. Populist and democratic rhetoric of land reform and the rights of labour complemented the language of progressive, state-led economic development. The Liberals governed New Zealand until 1912, but their rural wing was greatly reinforced from 1893 and labour’s influence correspondingly diminished. By 1905 a viable parliamentary group to the Liberals’ right was taking shape. Land policy was the key dimension. In encouraging closer settlement after 1890, the Liberals had instituted or developed a variety of tenures, including state leasehold. Controversies over the competing merits of leasehold and freehold were a defining theme in the politics of land, and while leasehold tenure appealed to many aspiring farmers, once these individuals became more established their enthusiasm for freehold increased. An emerging Reform Party championed the freehold, and in doing so made considerable inroads into the Liberals’ farmer base. It would not be too much to say that an alliance between wealthy and more modest farmers took shape over the freehold.[4] The Liberals themselves had become ardently imperialist after 1895, enthusiastically supporting London in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) and espousing naval rearmament around 1909.

At the same time, the Liberal grip on the working class was weakening. The most important labour legislation of the 1890s had established compulsory arbitration of industrial disputes. This law facilitated the development of trade unions and by 1910 union membership was very high.[5] After 1905, trade unions underwrote a succession of independent labour parties. At the same time there were tensions within the labour movement over organisation, strategy and tactics. To simplify a complex situation, a few unions (often but not always of highly skilled workers) continued to adhere to the Liberal party; many unions espoused, with increasing fervour, a socialist platform to be achieved through parliamentary means; and a militant bloc (concentrated among maritime workers, miners, and labourers) advocated a more or less syndicalist approach. The centre of gravity in labour politics shifted sharply to the left by 1914.[6]

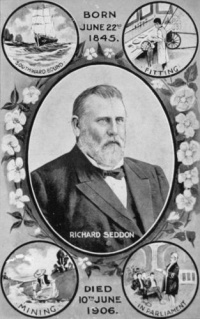

The 1911 general election elected a parliament that sat until the end of 1914; the results suggested that some realignment was beginning. The dominant Liberal had been Richard Seddon (1845-1906), who served as prime minister from 1893 to 1906. He was succeeded by Sir Joseph Ward (1856-1930), a merchant by occupation, a Roman Catholic Irish-Australian by background. Ward was a wily politician but he lacked Seddon’s brash populism and his evidently bourgeois lifestyle and affectations did little to reconcile an increasingly restive working class. From 1905, the new Reform Party was capably led by a small farmer, William Massey (1856-1925).

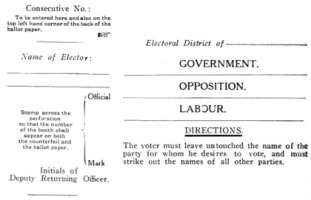

The House of Representatives was elected by simple plurality (commonly called "first past the post") until 1996, but for the elections of 1908 and 1911 runoff ballots were held where one candidate did not win a majority of the vote. The 1911 election is therefore rather difficult to analyse, and more so because there were Reform and Independent Reform, Liberal and Independent Liberal, and Labour and Independent Labour candidates. One authoritative calculation gives Reform and their independents 37 percent of the vote, the Liberals and their independents almost 45 percent, Labour candidates 8 percent and 10 percent distributed among other independents and the like.[7] Other estimates award the Liberals around 40 percent and Reform about 34 percent.[8] Reform had greatly increased its hold on the better off urban and more prosperous farming electorates; the Liberals remained strong in middling, and indeed working-class, urban seats and in some frontier farming districts. It is difficult to know whether the country quota much advantaged Reform, for Reform had urban support as well as rural. The same was true of the Liberals, although their rural support was declining.[9] In the end the question must be hypothetical, for one would have to know the details of each polling place, and moreover make some fairly heroic assumptions about the likely boundaries of electorates which lost the quota, and of course of their neighbours. In any case Reform picked up four more seats than the Liberals on at least 4,000 fewer votes. After some months of parliamentary manoeuvring, enough Independent Liberals or Liberals crossed the floor to install Reform.

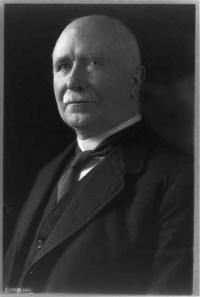

Massey, the new prime minister, had been born in the north of Ireland in 1856 and immigrated to New Zealand as a youth. He worked as a farm labourer for some years, eventually buying a small farm south of Auckland. All his life he was identified with the protestant, Orange tradition of Ulster and was a convinced Empire loyalist. Like many successful New Zealand prime ministers, Massey had had relatively little formal education but was extremely well read. Physically imposing and blessed with a strong constitution, Massey dominated parliament and his cabinet, the latter reflecting Reform’s coalition of gentlemanly and populist, urban and rural conservatives. Reform in fact won a fair measure of support from skilled workers in provincial towns. "Massey claimed to be the true Liberal, articulating a vision of a meritocracy and a more efficient nation based on a vibrant civil society and a property-owning democracy."[10]

A dominant theme of 1912 and 1913 was confrontation with the militant wing of the labour movement. On most other matters there was little enough difference between Liberal and Reform. Both believed in closer settlement of the land and in state infrastructure development, both wished to reinforce the respectable middle and skilled working class, and neither would yield to the other on empire loyalty or, indeed, on a more assertive defence policy.[11] Parliamentary leadership, generally, was still highly personalised rather than relying on formal party structures. While, by 1914, Reform and the Liberals had political committees throughout the country, many parliamentarians still cultivated personal power bases and Massey, like Seddon and Ward before him, "ruled largely through personal authority and political acumen."[12] Like Seddon and Ward, Massey treated the party caucus as a vehicle for announcing decisions rather than making them.[13]

War and the 1914 Election↑

In August 1914, most politicians, most newspapers, most institutions of civil society supported the British position. It is of course very difficult to get a sense of wider public opinion but there were large and apparently enthusiastic crowds in the towns and cities. The government’s war aims, essentially, were that New Zealand would "to do all in its power to help the empire to win the war, or at least not to lose it."[14] Accordingly an expeditionary force was assembled and despatched to Europe within weeks. Sending the force almost provoked a constitutional crisis, for Massey refused to allow it to sail without an adequate naval escort. When the governor, Arthur Foljambe, Lord Liverpool (1870-1941), suggested using his own authority as commander in chief to order immediate sailing, Massey made it clear he would resign. The governor backed down.[15]

For four months after the war began, however, the parliamentary situation remained unchanged. The election due at the end of 1914 took place and nearly resulted in a deadlocked parliament. The election was conducted under simple plurality. Reform came first in the popular vote, with somewhere between 45 and 47 percent to the Liberals’ 42 or 43 percent. Reform won forty of the eighty seats in the House, and the Liberals, again led by Ward, thirty-four. Labour was the wild card: labour candidates won six seats.[16] The 1911 election had returned four labour members (three of them "independent labour" and one standing as for the first New Zealand Labour Party). Labour’s political advance depended on displacing left-wing Liberals from working-class electorates. Two by-elections in 1913 achieved precisely that when a new Social Democratic Party won seats vacated by the deaths of Liberal incumbents. When parliament dissolved for the election at the end of 1914, therefore, there were six labour members: two identified with the SDP and the other four although identified as labour cultivating local powerbases rather than engaging with a national party. The state of labour’s representation reflected on-going divisions between "moderate" and "militant", although these labels were often over-used.[17]

The 1914 election left the Reform Party in a precarious position with exactly half of the seats in the House. Disputes over some results persisted until the middle of 1915, and eventually left Reform with forty-one. It was perhaps fortunate for Massey that a longstanding convention usually allowed Parliament not to meet until May or June (a parliamentary timetable which one wit described as tied to the reproductive rhythms of sheep).

Coalition and Labour’s Opposition 1915-19↑

When Parliament did meet at the end of June 1915 – fully seven months after having risen for the 1914 election – all parties had come under sustained pressure to form a coalition (or "national") government in the interests of wartime unity. That a coalition had not been formed earlier was, many thought, due to the personal enmity between Massey and Ward. Ward’s psyche was so bound up with political office that he saw his defeat in 1911 as something more than a political matter; he believed that the Irish Protestant Massey had played the sectarian card against Ward’s Catholicism.[18] Sectarianism had seldom been a significant dimension of New Zealand politics but it became somewhat more pronounced after 1912.[19]

A more telling reason why a coalition was not formed in 1914 was the general expectation that the war would be brief – once it became apparent that it would be prolonged, New Zealand was in the throes of the 1914 election and its long aftermath. Once the final distribution of seats was clarified, Massey realised that his majority was sufficiently slender to make a coalition attractive. Ward bargained hard, and the governor had to broker negotiations. Eventually Reform and the Liberals agreed on each having an equal number of ministers and Ward won back his old finance portfolio. In fact, Ward was almost equal to Massey, who of course remained prime minister.[20] The coalition would last four years, with the general election due at the end of 1917 being delayed two years.

The labour members had chosen to remain outside the coalition. Attitudes to the war within the labour movement varied widely. Some radicals opposed the war as an imperialist affair. Even among the many who did not share that view, there was a widespread feeling that the sacrifices necessary in wartime were not being equitably shared. In particular, there was criticism of the relatively generous prices that farmers received for their produce, as well as of the government’s apparent inability, or unwillingness, to regulate prices and profits sufficiently. Some scholars have recently emphasised that, after the confrontations of 1912-1913, "far from going out to bust the union movement, Reform made every effort to ensure that they did not antagonise the unions" in the interests of winning the war.[21] When the government moved towards imposing conscription in 1916, however, most labour activists opposed the measure as an unacceptable imposition on individual liberty. Some argued that conscription was the very militarism against which the war was allegedly being fought; others, that conscription would be unnecessary if soldiers were decently paid.

The threat of conscription was one factor in the establishment of the Labour Party. After the 1914 election, the two Social Democratic members had cooperated with the four other "labour" members, but the desire for a united voice against conscription encouraged a formal arrangement. Some activists feared that the government would sponsor a loyalist, pro-conscription "labour party" and these argued that the Labour name was "too valuable to be left lying around." Some militants thought that the war was capitalism’s final crisis, and therefore that labour unity was an essential prelude to guiding the revolution when it came. No doubt many simply regarded labour unity as essential, not least as the coalition of Reform and Liberal was, as they argued, the inevitable consequence of the two larger parties’ common ground on most substantial issues. All these currents came together in the Labour Party’s formation in July 1916.[22] The new party owed much to its radical predecessor, the SDP, and took over the objective of the "socialisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange", while the immediate platform also drew on reformist traditions and aimed at banking reform, the nationalisation of insurance and coastal shipping, progressive taxation and increased pensions, along with enhanced recognition of trade unions.[23] One labour member left the caucus over the new radicalism and thereafter sat as a Liberal.[24]

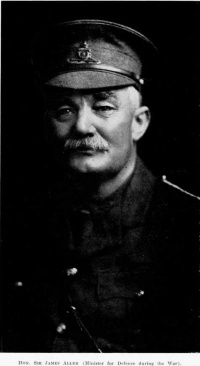

One odd dimension of the coalition was that Ward insisted on travelling overseas with Massey to imperial conferences and to visit the troops. On occasion this became almost farcical: at the end of 1916 the British government proposed that Dominion prime ministers meet with the British War Cabinet. Massey felt obliged to insist that Ward also attend, "since [Ward] threatened to go home if he was left out and, if Ward went home, Massey would have to follow to prevent Ward stabbing him in the back."[25] The British withdrew their suggestion. Massey and Ward were overseas for nearly twenty-four months on three long trips between August 1916 and August 1919, and much of the responsibility for leading the government fell on the Defence Minister, Reform’s James Allen (1855-1942) who, although an efficient administrator, was never forgiven by radicals for his stern approach to dissent and conscientious objection.[26]

To an increasing degree, and perhaps inevitably, the government was managed by ministerial decree rather than parliamentary resolution. The long-term consequence of the coalition was that the Liberals were increasingly implicated in the unpopular dimensions of wartime government, while getting little credit from Reform voters. Labour, however, capitalised on a good deal of working-class dissatisfaction in a series of by-elections in 1918, increasing its net strength by one seat. One of them had been occasioned by the conscription of the young miners’ MP, Paddy Webb (1884-1950), and his subsequent refusal to serve. Imprisoned, he lost his right to sit in parliament and was replaced by the austere Marxist Harry Holland (1868-1933) who would go on to lead Labour for fifteen years.[27] In another, a deceased labour member was replaced by Peter Fraser (1884-1950) who would serve as prime minister from 1940 to 1949.

Perhaps well aware of the need to reinforce his party’s progressive credentials, shortly after he and Massey returned home from the Versailles negotiations, in August 1919, Ward led the Liberals out of the coalition without warning Massey.[28] In the election at the end of that year, Ward issued a radical manifesto, hoping to blunt Labour’s advance. It was a strategy that had only very partial success, for the Liberals were seriously weakened, and Labour increased its vote particularly in working-class electorates, while Reform won an absolute majority in the House.[29]

Conclusion↑

New Zealand’s parliament was, in one sense, remarkably stable during the First World War. Although the single-party Reform government formed a coalition with the Liberals in 1915, William Massey continued as both prime minister and the dominant figure in the government. Nor did policy change much as a result of the coalition. In few other Allied states was such continuity evident, and part of the explanation is the relatively minor difference in policy between the two parties. The other major consequence of the war for New Zealand’s parliamentary system was the creation of a new Labour party, which speedily consolidated support among urban workers and miners, and more slowly displaced the Liberals as the dominant vehicle for reformist politics. Only in 1936 would Labour and a new moderate conservative National Party dominate a renewed two-party system.

Jim McAloon, Victoria University of Wellington

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ Atkinson, Neill: Adventures in Democracy. A History of the Vote in New Zealand, Dunedin 2003, pp. 72-76.

- ↑ McLean, Gavin: Governors. New Zealand’s Governors and Governors General, Dunedin 2006, pp. 136-142; McIvor, Timothy: The Rainmaker. A Biography of John Ballance, journalist and politician 1839-1893, Wellington 1989, pp. 206f, 224f.

- ↑ McIntyre, W. David: Dominion of New Zealand. Statesmen and Status 1907-1945, Wellington 2007, p. 61, see also p. 67.

- ↑ See, generally, Brooking, Tom: Lands for the people? The Highland clearances and the colonisation of New Zealand, a biography of John McKenzie, Dunedin 1996.

- ↑ Olssen, Erik: The Origins of the Labour Party. A Reconsideration, in: New Zealand Journal of History 21/1 (1987), pp. 79-96.

- ↑ Gustafson, Barry S.: Labour’s Path to Political Independence, Auckland 1980; Nolan, Melanie (ed.): Revolution. The 1913 Great Strike in New Zealand, Wellington 2006; Olssen, Erik: The Red Feds. Revolutionary Industrial Unionism and the New Zealand Federation of Labour 1908-14, Auckland 1988.

- ↑ Bassett, Michael: Three party politics in New Zealand, 1911-1931, Auckland 1982, p. 66.

- ↑ GENERAL ELECTIONS 1890-1993, issued by Electoral Commission New Zealand, online: http://www.elections.org.nz/events/past-events/general-elections-1890-1993 (retrieved: 9 September 2013).

- ↑ Chapman R. M.: The Political Scene 1919-1931, Auckland 1969, pp. 66ff.

- ↑ Olssen, Erik: Towards a Reassessment of W. F. Massey. One of New Zealand’s Greatest Prime Ministers (Arguably), in: Watson, James / Paterson, Lachy (eds.): A Great New Zealand Prime Minister? Reappraising William Ferguson Massey, Dunedin 2011, pp. 15-30, quote at p. 18.

- ↑ Gustafson, Barry: Massey, William Ferguson, issued by Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2m39/massey-william-ferguson (retrieved: 13 November 2013).

- ↑ Martin, John E.: The House. New Zealand’s House of Representatives, 1854-2004, Palmerston North 2004, p. 148.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ McGibbon, Ian: The Shaping of New Zealand’s War Effort, August-October 1914, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian (eds.): New Zealand’s Great War. New Zealand, the Allies and the First World War, Auckland 2007, pp. 49-68, quote at p. 57.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 66.

- ↑ Bassett, Three Party Politics 1982, p. 66; GENERAL ELECTIONS 2013.

- ↑ See, generally, Gustafson, Labour’s Path 1980.

- ↑ Bassett, Michael: Sir Joseph Ward, Auckland 1993, p. 200.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 229.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 222-225.

- ↑ Olssen, Massey 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ Among other works, see Gustafson, Labour’s Path 1980; Olssen, Origins 1987.

- ↑ MW 12 July 1916 p. 5.

- ↑ Gustafson, Labour’s Path 1980, p. 112.

- ↑ Mcintyre, Dominion 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Baker, Paul: King and Country Call. New Zealanders, conscription and the Great War, Auckland 1988.

- ↑ O'Farrell, Patrick: Holland, Henry Edmund, issued by Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3h32/holland-henry-edmund (retrieved: 30 October 2012); Richardson, Len: Webb, Patrick Charles, issued by Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3w5/webb-patrick-charles (retrieved: 1 April 2014).

- ↑ Bassett, Ward 1993, p. 244.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 244ff.

Selected Bibliography

- Atkinson, Neill: Adventures in democracy. A history of the vote in New Zealand, Dunedin 2003: University of Otago Press.

- Baker, Paul: King and country call. New Zealanders, conscription, and the Great War, Auckland 1988: Auckland University Press.

- Bassett, Michael Edward Rainton: Sir Joseph Ward. A political biography, Auckland 1993: Auckland University Press.

- Bassett, Michael Edward Rainton: Three party politics in New Zealand, 1911-1931, Auckland 1982: Historical Publications.

- Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing.

- Gustafson, Barry: Labour's path to political independence. The origins and establishment of the New Zealand Labour Party, 1900-19, Auckland; Wellington 1980: Auckland University Press; Oxford University Press.

- Martin, John E.: The house. New Zealand's House of Representatives, 1854-2004, Palmerston North 2004: Dunmore Press.

- McIntyre, W. David: Dominion of New Zealand. Statesmen and status, 1907-1945, Wellington 2007: New Zealand Institute of International Affairs.

- Olssen, Erik: The origins of the Labour Party. A reconsideration, in: New Zealand Journal of History 21/1, 1987, pp. 79-96.

- Watson, James / Paterson, Lachy (eds.): A great New Zealand prime minister? Reappraising William Ferguson Massey, Dunedin 2011: Otago University Press.