The Pacifist↑

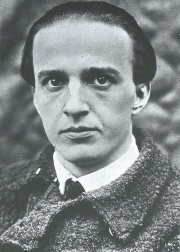

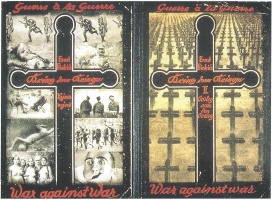

Pacifist, anarchist, educator, free thinker, philanthropist, Bürgerschreck: the founder of the first anti-war museum (founded on 1 August 1923[1] and opened in Berlin in 1925) and editor of the illustrated volumes Krieg dem Kriege (War Against War, 1924 and 1926) cannot be represented by one term alone. Ernst Friedrich (1894-1967) was born the youngest of thirteen children in Breslau. His mother was purportedly a washerwoman, his father a saddler.[2] As a young man, Friedrich embarked on an apprenticeship as a printer, which he did not complete, and then became a factory labourer. He was passionate about the theatre and first appeared on stage in Breslau in 1914.[3] He joined the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1911, but left the party again in protest of its approval of war loans. Throughout his life, he was a non-conformist.[4] As a close friend of Karl Liebknecht’s (1871-1919), he also frequently worked with trade unions. In 1914, he registered as a conscientious objector and was subsequently institutionalised.[5] In 1916, he organised an anti-militaristic, revolutionary youth movement. He resisted being drafted once again in 1917, which this time led to his arrest. The years of the Weimar Republic and the National Socialist regime brought further court proceedings, prison sentences and physical torture.

The Anti-War Museum↑

The Anti-War Museum was opened in Parochialstraße in Berlin in 1925. In his book From Peace Museum to Hitler Barracks, Friedrich tells the story of how he restored the building himself with the help of a builder friend and a small loan from a nearby builder’s supply shop.[6] His grandson Tommy Spree adds, though, that the museum could not have been maintained without the financial support of the Israel family, who ran the large Berlin department store Nathan Israel.[7] Friedrich does not mention this; the “genius of communication” preferred to style himself as a fighter.[8] Often close to bankruptcy, he managed to keep afloat by publishing vigorously.[9]

As he did in the illustrated volumes Krieg dem Kriege, Friedrich displayed disturbing photographs in the museum of maimed and naked soldiers, hanged partisans, firing squad victims, raped women, mass graves, starved children, slaughtered animals, destroyed churches and disabled war veterans. The accompanying captions (in four languages) gave the images a political interpretation, and Friedrich often juxtaposed them with quotes from war propaganda and reports. The large range of topics, as well as Friedrich’s obvious editorial stance – in his view, soldiers were not only victims but also professional killers – account for the important position his publications have held to the present day.

The museum was a thorn in the side of the political right and the National Socialists. Its windows were regularly smashed in and its pictures and documents torn from the walls. A number of court cases – including charges of attempted high treason – resulted. Once released from “protective custody,” Friedrich decided to leave the country in December 1933. He sent archival materials, as well as the printing plates for his books, abroad ahead of him. His exile took him from Prague to Switzerland, where he was evicted for libel of a “friendly statesman” (Hitler) in his 1935 book Vom Friedens-Museum zur Hitler-Kaserne, in which he had documented the destruction of his museum by the SA. He was granted asylum in Belgium and opened his second anti-war museum in Brussels in 1936; it was destroyed by German forces in 1940. In March 1943, Friedrich the pacifist finally donned a uniform – side by side with the French Résistance, he fought the Germans, having been sentenced to death in absentia. (Tommy Spree writes that his grandfather was unlikely to have participated in actual combat, but had probably been a courier.[10]) Friedrich became a French citizen in 1948.[11]

After World War II↑

Friedrich’s offer to establish yet another anti-war museum in Berlin or Nuremberg finally failed in 1950 – in the middle of the Cold War – due to resistance (or lack of support) from the political establishment.[12] Friedrich, who had campaigned all his life for youth, understanding, and the right to grow up without violence, invested his reparations, the advance on his pension and a loan into the purchase of a small island in the Marne in 1955. On the island – which was renamed Île de la Paix (from Île du Moulin) in 1961 – he organised youth conventions, partly with help from the German union ÖTV (Öffentliche Dienste, Transport und Verkehr, Public Service, Transport and Traffic Union). A stable cooperation with the ÖTV had, however, not been established by the time of his death on 2 May 1967. The island was eventually sold in order to meet inheritance expenses and Friedrich’s papers destroyed. In 1982, Friedrich’s grandson, Tommy Spree, re-opened the anti-war museum in Berlin. Like Henri Barbusse (1873-1935), Ernst Friedrich was convinced that “humans are machines for forgetting”[13] – an assessment which still holds true today.

Susanne Brandt, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Friedrich, Ernst: Vom Friedens-Museum zur Hitler-Kaserne, Geneva 1935, p. 1.

- ↑ In his memoirs, Henry Jacoby contests that Friedrich’s mother had been a washerwoman and states that Friedrich liked to dramatise his origins. Jacoby, Henry: Von des Kaisers Schule zu Hitlers Zuchthaus. Eine Jugend links-außen in der Weimarer Republik, Frankfurt am Main 1980, p. 68.

- ↑ Spree, Tommy / Oelze, Patrick: Ich kenne keine Feinde. Zur Biografie Ernst Friedrichs (1894-1967), in: Friedrich, Ernst: Krieg dem Kriege, new edition by the Anti-Kriegs-Museum Berlin with an introduction by Gerd Krumeich, Berlin 2015, p. xxxix-lxxi, here: p. xl f.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Ein einzigartiges Werk, in: Friedrich, Krieg dem Kriege, Berlin 2015, p. xiii.

- ↑ Tommy Spree emphasises that the exact timeline of arrests and institutionalisations remains unclear: Spree / Oelze, Ich kenne keine Feinde, p. xliii.

- ↑ Friedrich, Vom Friedens-Museum zur Hitler-Kaserne, p. 9f.

- ↑ Spree / Oelze, Ich kenne keine Feinde, p. lv.

- ↑ Krumeich, Ein einzigartiges Werk, p. xvii.

- ↑ Spree / Oelze, Ich kenne keine Feinde, p. lii.

- ↑ Ibid., p. lxvi.

- ↑ Ibid., p. lxviii.

- ↑ Linse, Ulrich: Der unzeitgemäße Ernst Friedrich, in: Mytze, Andreas (ed.): Ernst Friedrich zum 10. Todestage, Europäische Ideen 29 (1977), p. 2. Cf.: Friedrich, Ernst: Berlin – Du treulose Tomate!, in: Mytze: Ernst Friedrich zum 10. Todestage, p. 59.

- ↑ Friedrich, Ernst: Das Anti-Kriegs-Museum, Berlin 1926, p. 4.

Selected Bibliography

- Friedrich, Ernst: Krieg dem Kriege, Berlin 1924: Verlag 'Freie Jugend'.

- Krumeich, Gerd (ed.) / Friedrich, Ernst: Krieg dem Kriege, Munich 2004: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt

- Krumeich, Gerd / Spree, Tommy / Oelze, Patrick (eds.) / Friedrich, Ernst: Krieg dem Kriege, Berlin 2015: Ch. Links Verlag

- Mytze, Andreas W. (ed.): Europäische Ideen 29. Ernst Friedrich zum 10. Todestag, Berlin 1977: Verlag Europäische Ideen.