Introduction↑

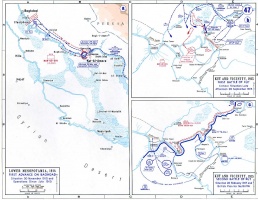

The capitulation of the ill-prepared British-Indian expeditionary force at Kut al-ʿAmāra on 29 April 1916 did not dramatically alter the overall military situation in Mesopotamia, but it dealt a severe blow to British military prestige. This humiliating experience can be seen as a decisive reason for the second British advance on Baghdad, which was prepared at considerable expense and which deployed massively reinforced troops. By May 1916, both sides had consolidated their positions. However, a substantial part of the Ottoman 6th Army in Iraq was engaged in fighting the Russian advance in Western Persia, occupying Hamadan on 10 August 1916, while the British and Indian troops, under the command of General Frederick Stanley Maude (1864-1917) from July 1916, prepared for a second advance on Baghdad along the Tigris, paying considerable attention to improving medical and transport facilities to supply their troops.

The Fall of Baghdad↑

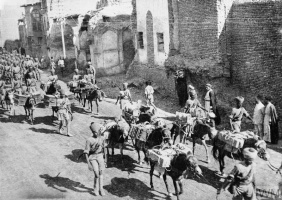

The offensive began in mid-December 1916, involving ca. 50,000 troops. The Ottoman 6th Army was outnumbered by a factor of three to five, but put up stiff resistance, inflicting heavy casualties on the British side of around 15,000. On 23 February, the British won the second battle of Kūt al-ʿAmāra. Although the Ottoman troops managed to retreat in an orderly fashion, they had suffered heavy losses and were unable to establish a stable line of defense downstream from Baghdad. Aggravating the situation was the fact that Halil Pasha (1882-1957) was late in deciding to recall the Ottoman troops from Hamadan. By the time they finally arrived at the Ottoman-Persian border, it was too late to deploy them for the defense of Baghdad.

On 26 February, the Ottoman military commander Halil Pasha ordered the transfer of the Ottoman administration from Baghdad to Samarra. There was a working section of the Baghdad railway between the two towns that could be used for transport. A large number of important Ottoman administrative documents relating to the civil administration of the province were also relocated, only to be destroyed in a shipwreck on the Tigris when shortly afterwards the Ottoman headquarters were moved again, this time from Samarra to Mosul. On 10 March, faced with the continuing advance of British troops, Halil Pasha, with some reluctance, ordered all military personnel to evacuate Baghdad. Military equipment that could not be removed was destroyed, including a newly installed German wireless telegraph system. Several administrative buildings and installations of the Baghdad railway (but not the station itself) were blown up and the pontoon bridge over the Tigris set on fire. As soon as the Ottoman authorities had left the city during the night, crowds reportedly began looting the bazaar and adjacent stores until the arrival of the British vanguard the next morning restored order.

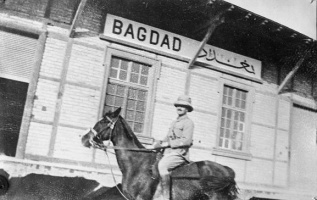

When General Maude arrived later that day, a proclamation was publicly read out to the people of Baghdad and the province, in which the British declared their good intentions towards the populace, invoking the proud past of the country and its decline since the Mongol occupation, which, it was claimed, had found its continuation in Ottoman misrule.

Aftermath↑

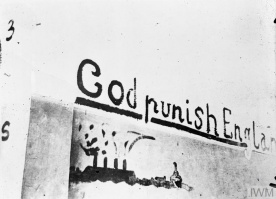

The fall of Baghdad did not pose an immediate military threat to the existence of the Ottoman state. Although the British army continued to push up the Tigris, and the Ottoman forces of the 6th Army were in a deplorable state, no serious decisive move was attempted by the British forces until the end of the war. However, the symbolic, economic and strategic impact was considerable. The fall of Baghdad was not officially acknowledged by the Ottoman government and preparations were soon made for a counter-offensive as part of the operations of what was known as the “Yıldırım Army Group”. However, these had to be cancelled due to the deteriorating military situation in Syria.

Christoph Herzog, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg

Managing Editor: Nazan Maksudyan

Section Editor: Erol Ülker

Selected Bibliography

- Herzog, Christoph: Osmanische Herrschaft und Modernisierung im Irak: die Provinz Bagdad, 1817-1917, Bamberger Orientstudien, Bamberg 2012: University of Bamberg Press.

- Larcher, Maurice: La guerre turque dans la guerre mondiale, Paris 1926: Berger-Levreault.

- Majd, Mohammad Gholi: Iraq in World War I. From Ottoman rule to British conquest, Lanham 2006: University Press of America.

- Moberly, F. J.: The campaign in Mesopotamia 1914-1918, 4 volumes, London 1923-1927: Her Majesty's Stationery Office