Eugene Debs Prior to World War I↑

Born in Terre Haute, Indiana, Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926) was one of the most prominent native-born American radicals. After dropping out of school at the age of fourteen to take a position as a laborer for the Terre Haute and Indianapolis Railway Company, Debs rose to become the president of the American Railway Union. After the Panic of 1893, Debs led a boycott of Pullman railroad cars after George Pullman (1831-1897) announced a wage decrease without reciprocal rent reductions in Pullman’s company town. For his role in this event, he was arrested on charges of conspiracy and ultimately served six months in the Woodstock, Illinois jail for contempt of court. Following his prison sentence, Debs announced his conversion to socialism in 1897, and earned the nomination as the Socialist Party candidate for president in every election from 1904-1920, although he declined the nomination in 1916.

Debs’ Opposition to World War I↑

During World War I, Debs emerged as one of the most vocal opponents of America’s participation in the war. As a result, the federal government charged Eugene Debs with violating the Espionage Act. After a jury convicted him, a judge sentenced him to ten years in prison, of which he served only three years.

Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party, and World War I↑

In the early years of World War I, Debs was often bedridden due to frequent occurrences with exhaustion and sickness. Due to his weakened physical state, which also kept him from running for president in the election of 1916, the Socialist Party of the United States suffered from a lack of leadership. American socialists became increasingly divided on the issue of whether the Party should support patriotic preparedness campaigns, favored by Milwaukee socialists including Representative Victor Berger (1860-1929) and Mayor of Milwaukee, Daniel Hoan (1881-1961), or condemn the war effort. Ultimately, the Socialist Party, under the direction of Morris Hillquit (1869-1933), tried to unify itself by presenting an official stance opposing both the war and military conscription.

The Canton, Ohio Speech↑

By 1918, the U.S. government began to imprison socialist dissidents who voiced their war opposition. In Canton, Ohio on 16 June 1918, Debs delivered his most famous anti-war speech. The Canton speech did not differ much from earlier speeches he had given on the topic, but on this day, the district attorney for Northern Ohio, Edwin S. Wertz (1875-1943?), had stenographers carefully record the precise words of Debs’ speech.

In delivering the speech at Nimisilla Park, Debs had chosen a symbolic location, as the park was not far from the Canton jail where three socialists, Charles Ruthenberg (1882-1927), Alfred Wagenknecht (1881-1956), and Charles Baker, were held in jail for violation of the Espionage Act. Proclaiming that his three comrades were “paying the penalty” for trying “to make democracy safe in the world,” Debs highlighted the hypocrisy of America’s rationale for going to war abroad, while suppressing freedom of speech at home. His speech provided a blistering assault against the United States government, which had silenced wartime critics; he also included a long list of injustices committed against his fellow comrades, including Kate Richards O’Hare (1877-1948), who was imprisoned for violating the Espionage Act, and Tom Mooney (1882-1942), who had been convicted on limited evidence of bombing a preparedness parade in San Francisco. Debs further attested that the true purpose of the war was for the “Wall Street junkers” and “vampires” to “conquest and plunder,” while it was the “working class who fight all the battles.”[1]

The Canton speech not only stands as an act of explicit defiance to federal law, but it also represents Debs’ convictions understanding that it could potentially lead to a conviction. Ultimately, the speech landed Debs in prison.

U.S. v. Debs Trial and Conviction↑

In the Canton speech, Debs was careful to not explicity call upon his audience to avoid the draft, and even the U.S. Attorney General, Thomas W. Gregory (1861-1933), was unsure if the speech would be enough to successfully prosecute Debs. Nevertheless, government agents arrested Debs and indicted him for violating the Espionage Act. In the case of U.S. v. Debs, the government gathered minimal evidence that Debs’ speech had motivated Americans to avoid conscription; instead prosecutors argued that Debs’ speech represented a threat that could potentially influence Americans to be disloyal. After the prosecution concluded its case, Debs’ defense team called no witnesses on Debs’ behalf, with the exception of Debs himself, who provided an appeal to the jury on 11 September 1918. His infamous appeal stood as a testament to his martyrdom as he proclaimed “I do not fear to face you in this hour of accusation...I can look you in the face, I can look the world in the face, for in my conscience, in my soul, there is no festering accusation of guilt.”[2]

After deliberating for six hours, the jury pronounced Debs guilty on three counts, and ruled that he had tried to incite refusal of military service in opposition to United States law. The judge sentenced him to ten years at the Moundsville State Penitentiary in West Virginia.

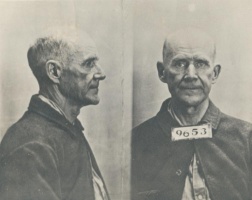

Convict 9653 and the Election of 1920↑

After being transferred from Moundsville to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, Debs’ supporters crafted a “jail to the White House” campaign. His campaign had a minimal chance of success, as partisanship had split socialists from communists in America, although both factions joined together to cast their ballots for Debs. While the president pardoned some radicals convicted under the Espionage Age (such as Kate Richards O’Hare), President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) refused to grant amnesty to Debs prior to the election. Debs promoted his campaign as a vote for “Convict 9653,” and tallied over 913,000 votes, which was the largest number of popular votes earned by a Socialist candidate, even though it was only 3.4 percent of the total votes cast. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding (1865-1923) commuted Debs’ sentence to time served.

Legacy and Historiography↑

Debs continues to be known as one of America’s most prominent labor leaders and political radicals. Historians have tended to portray him as lacking intellectual depth and knowledge of socialist theory, but as a gifted orator, spokesperson for the working-class, and opponent of war. Debs’ wartime conviction helped lead to the formation of the American Civil Liberties Union; indeed, historian Eric Foner called the 1920s “the birth of civil liberties.”[3] In remembering Debs, socialist leader Norman Thomas (1884-1968) perhaps said it best, claiming that Debs was not “the intellect of the Party, but he was emphatically the heart of the Party.”[4]

Kyle Anthony, University of Saint Mary

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Brommel, Bernard J.: Eugene V. Debs. Spokesman for labor and socialism, Chicago 1978: Charles H. Kerr.

- Foner, Eric: The story of American freedom, New York 1998: W. W. Norton.

- Freeberg, Ernest: Democracy's prisoner. Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the right to dissent, Cambridge; London 2010: Harvard University Press.

- Ginger, Ray: The bending cross. A biography of Eugene Victor Debs, New Brunswick 1949: Rutgers University Press.

- Salvatore, Nick: Eugene V. Debs. Citizen and socialist, Urbana 1982: University of Illinois Press.

- Tussey, Jean Y. (ed.): Eugene V. Debs speaks, New York 1970: Pathfinder Press.