Biography↑

Youth↑

George Creel (1876-1953) was born in rural West Central Missouri on 1 December 1876. His parents Henry Creel (1829-1907) and Virginia Creel (1846-1937) moved several times during George Creel’s youth, settling east of Kansas City in Odessa, Missouri. George’s father Henry was an alcoholic and had difficulty holding down steady work. Creel's mother Virginia supported the family by keeping borders and doing sewing. Creel had a very close relationship with his mother, sometimes cited as the reason for his avid interest in the women’s suffrage movement during the progressive era. Though George Creel had little formal schooling, it appears that he was well-read, particularly in the classics. Creel attended Odessa High School and Odessa College for a short time.

Prewar Career↑

At the age of twenty, George Creel began working as a reporter for the Kansas City World Newspaper. Over time, his responsibilities grew to include some assignments that required investigative journalism, writing book reviews and uncovering significant social events. He left the Kansas City World Newspaper and traveled to New York City, reportedly by hopping freight trains. While in New York City, Creel supported himself by writing jokes for William Randolph Hearst’s (1863-1951) and Joseph Pulitzer’s (1847-1911) newspaper syndicates, among others.

He moved well in the circles of the city's social elite. In 1899, he returned to Kansas City and started The Kansas City Independent newspaper, backed by the financial support of Arthur Grissom (1869-1901). Although Grissom soon ended his relationship with the paper, Creel continued as the editor and publisher. For the next nine years, Creel established himself as a progressive journalist. In 1909, Creel effectively abandoned the newspaper and moved to Denver, Colorado where he found work with the Denver Post. He continued his muckraking style of journalism in support of various progressive causes in Colorado, mostly calling for the expansion of public utilities, particularly the public ownership of Denver’s water company. Creel resigned from the post after calling for public lynchings of Colorado state senators who were opposed to the expansion of public utilities.

George Creel continued to work for the Rocky Mountain News throughout 1911-1912, where he wrote in support of the candidacy of Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) for President. He accepted an appointment as Police Commissioner of Denver, then ordered the Denver Police to turn in their truncheons in an effort to lessen the possibility of any abuse of power by the police. He also embarked on a campaign to eliminate prostitution in the city.

In 1916, he joined the Wilson presidential campaign, writing articles and conducting interviews for the Democratic National Committee press office. His success in these fields led to increasing contact with Woodrow Wilson, which opened the door for his move to the Committee on Public Information (CPI) during the First World War.

Wartime Activities and Committee on Public Information↑

As head of the CPI, Creel convinced the Wilson Administration, and primarily Wilson himself, to avoid outright censorship and instead focus on managing the press and public relations by placing favorable articles thus shaping the overall message, and encouraging self-censorship through patriotic appeals to the editors and publishers of the major newspapers and magazines. Creel himself managed the Committee’s widespread operations, its overall relationship with the War, Navy and State Departments, as well as the newspaper and magazine industry. Other journalists, publicists, filmmakers and entrepreneurs approached Creel with ideas and were responsible for the actual writing and production of materials for both domestic and foreign consumption.

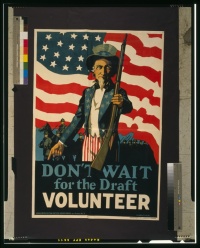

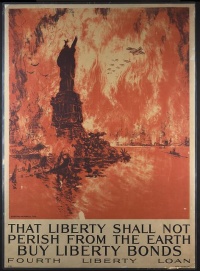

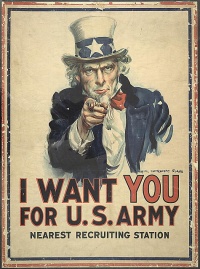

Poster campaigns for Liberty Loan Drives form some of the most memorable and iconic images of the First World War for Americans. The Division of Pictorial Publicity produced and disseminated the posters and other visual images. The Four Minute Man Division produced and managed the Four Minute Men who presented short four-minute speeches in a wide range of venues: vaudeville shows, fairs and movie houses. This effort seemed tailored to the current American marketing efforts which focused on door-to-door sales techniques, as well as the concept of the sales pitch’ itself.

While there were many departments and divisions of the Committee, the two principal sub-organizations in terms of managing and shaping the story for the government were the News Division and the Censorship Committee. The News Department produced thousands of articles tailored to fit into the myriad local, regional and national print outlets, primarily newspapers and magazines. By providing the news media with "the story," the News Division often short-circuited independent efforts to gather news by the papers and magazines themselves, effectively resulting in controlling what the papers printed by providing them with free content.

While it was very active and effective, the Censorship Committee was not oppressive per se, suppressing only relatively few stories that were deemed dangerous or seditious to the war effort. Creel's overall approach of managing and shaping the story that made it into the news media resulted in very favorable press coverage with the newspapers and magazines, and even Hollywood's big names began acting almost as agents of the government, using the material Creel's Committee provided them with. It is also clear that while the material circulated by the Committee was naturally very biased, the sheer quantity of news releases overwhelmed most opposition to its management of the story.

Edward Bernays (1891-1995), psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s (1856-1939) nephew and later major public relations "guru" of the 20th century, worked under Creel in the Committee, as did Walter Lippmann (1889-1974) and Carl Byoir (1886-1957). All three men developed and honed the basic techniques of the Committee in their later careers in public relations to manage and shape public opinion.

After the war, Creel continued his writing career and was active in progressive politics in the western states, running for Governor of California in the Democratic Party’s Primary in 1930. He lost to Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), who subsequently lost to Republican James Rolph Jr. (1869-1934) in the general election. Creel died in 1953.

John T. Broom, Norwich University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Axelrod, Alan: Selling the Great War. The making of American propaganda, New York 2009: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Creel, George: How we advertised America. The first telling of the amazing story of the Committee on Public Information that carried the gospel of Americanism to every corner of the globe, New York; London 1920: Harper & Brothers.

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Stone, Geoffrey R.: Perilous times. Free speech in wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the war on terrorism, New York 2004: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Vaughn, Stephen: Holding fast the inner lines. Democracy, nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information, Chapel Hill 1980: University of North Carolina Press.