Introduction↑

The centenary of the First World War in the United States was marked by determination at a national and regional level to frame the conflict as a highly significant part of modern American history. One hundred years after the end of a conflict that was characterised by politicians and newspapers in the United States after August 1914 as the “European War,” the First World War was represented to the wider public as a conflict that defined the nation. Institutions, charities and organisations across the country were mobilised from 2014 onwards to provide lectures, guides, displays and exhibitions that focused on establishing the First World War as part of the national narrative. This attempt to rescue or retrieve the conflict was based on the perception that this is a war that has been lost to social or collective memory. Indeed, the First World War has frequently been regarded as the “forgotten war” within the history of the United States during the 20th century. Overshadowed by the events of the Second World War and the divisions formed by the Vietnam War, the First World War often appears as a footnote to the seemingly more influential events that are remembered in the United States.

The centenary of the conflict was used by federal and state institutions, museums, galleries and community groups to rectify this apparent amnesia and to establish the First World War as the formative point of the “American Century”. This placement of the conflict in this established narrative of American ascendancy was highly important; it enabled the war to be remembered as part of the processes that saw the United States emerge as the world’s preeminent superpower. In this manner, the war can be represented within a wider narrative; to remember the war is to place it alongside the established account of war and memory within the “American Century”. With the anniversaries of the entry into the war, the major battles and the denouement of the conflict, a modern American memory of the First World War emerged which stressed its significance for understanding the 20th century. By examining the events, exhibitions and representation of this new commemoration, the way in which the First World War was brought to the attention and understanding of contemporary society in the United States can be assessed.

The Great War and Modern American Memory↑

Scholars of American memory have noted that the First World War appears, within the nation’s commemoration of modern conflict, as a minor detail in the history of the 20th century.[1] This has led many to assume that this is a war that has been neglected and perhaps cast aside in the schemes of national memory. Some have noted the absence of any grand national sites of memory as a reason for this absence, but such observations do not address the array of locations where the remembrance of the First World War was maintained in the immediate aftermath of the war. From the legion of Doughboy statues that adorn the squares of towns and cities across the United States to the plaques, sculptures and flagpoles that were erected by schools, businesses and charities to honour the memory of the dead, this was a war that was not forgotten.[2] However, it was a war that had disputed meanings. From neutrality, to belligerence, to mourning, the conflict’s meaning was open to debate in the United States and its commemoration proved difficult to negotiate.[3] Whilst local areas commemorated the dead, a wider national narrative about the meaning and purpose of the war was absent.

In the context of the wider events of the 20th century, the war appears to lack the grand narrative of victory and the “greatest generation” connected to the Second World War. Even the divisive memory of the Vietnam War appears to offer greater perspective on American society than a conflict that seems to possess no direct message. From a European perspective, the American memory of the First World War may have appeared to be lost, but it has just been remembered in a very different set of circumstances than in Britain, France, Germany and Italy. With the advent of the centenary of the war and the participation of former combatant nations from across the world in commemorative schemes, the United States was drawn into creating remembrance of a war that had not been central to national memory. As such, a new American memory, which recast the collective meaning of the war for the nation, emerged from the centenary.

Organising Remembrance and Retrieving the Memory of the War↑

As Britain and France announced schemes for the commemoration of the First World War and international programmes of remembrance were initiated from 2012, the focus on the American response to the centenary built within public, media and political spheres. With the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq still prominent and highly influential, there was a significant domestic drive to make a meaningful contribution to the marking of the First World War. The organisation of the centenary of the First World War across the United States was duly carried out by the United States World War I Centennial Commission, which was created by an Act of Congress in 2013. The purpose of this commission, which did not draw upon federal funds for activities, was to:

Central to the commission was the idea that the First World War was important, as it saw the sacrifice of citizens for an event that marked the beginning of the “American Century”. The inclusion of the First World War in this narrative was highly significant. The term emerged after the Second World War to define the nation’s global mission. It was subsequently incorporated into historical assessments of the course of the post-1945 world. The connection provided official recognition of the First World War as a core part of the national myth and memory that surrounds the commemoration of modern conflict. This was the centre of the new American memory of the First World War; an imagined connection that gave overarching meaning to a conflict that had previously lacked a place in the narrative of the nation.

It was on this basis that the centennial commission set to work. The commission operated at a federal level to raise funds and awareness, and provided support and guidance for devolved state centennial commissions, which coordinated operations at a regional level. Each of these state organisations shared the same objective: to see the conflict brought to the fore and remembered by the public as part of the “American Century”. The commission was aided in this work by the inclusion of notable historians on its advisory board. This undoubtedly enriched its activities at the federal and state levels and ensured that the focus was on public outreach and engagement. The work included the essential “qualities” of remembrance:

These objectives set out the character, form and function of the American memory of the First World War during the centenary. The commission aimed to restate the significance of the conflict, to educate and inform individuals and communities of its relevance and to remember the sacrifice of those who contributed to the war effort. The act of remembrance was a very important feature. The process of rescuing the memory of the war from neglect was represented as the key function of the commission. The excavation of the event from the nation’s consciousness and assertion of its importance in a wider narrative was essential. The collective “heroism and sacrifice” was brought to the fore in this manner as a means of promoting the significance of the conflict within American society. In this new framework of memory, the war was firmly placed as the originating point of the “American Century”; the event that ushered in a new consciousness within the American government and the American people.[6] The commission was able to promote schemes and projects to ensure this new memory was a central part of the commemoration of the war in the United States. This use of memory is key, as it could form the basis of ensuring that the war is maintained as a present point of commemoration within American society.

Remembering the First World War and the American Century↑

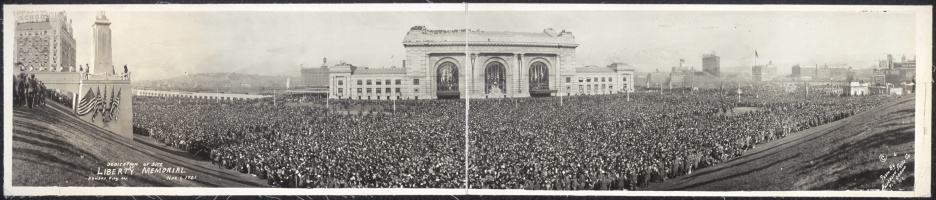

In 2017, the Centennial Commission worked at a federal and state level to ensure that the centenary of the declaration of war was marked across the nation. In the programmes of activity, the message of retrieving a lost memory, emphasis on significance and reframing of the war within the “American Century” were key. The centre of activity was the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. This site opened to the public in 1926 as the Liberty Memorial through the efforts of local philanthropists and obtained a designation as the nation’s centre of remembrance for the conflict in 2004. On 6 April 2017, the memorial played host to a special multimedia event which combined live performances, historical re-enactments and commemorative readings by representatives from across the world. The occasion was entitled In Sacrifice for Liberty and Peace: Centennial Commemoration of the U.S. Entry into World War I.[7] The focus on liberty and echoed the words of President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) in his speech of 2 April 1917 that the “world must be made safe for democracy” and the nation would ensure this. It also served to facilitate the modern American memory of the war as the originating point of the “American Century”. In advance of the commemoration at the museum, one of the members of the World War I Centennial Commission spoke of the significance of the conflict for the United States:

In this manner, In Sacrifice for Liberty and Peace provided an assertion of the war as a point of collective endeavour; this was a conflict that redefined the nation’s identity and brought individuals together to forge the “American Century”. The same theme of commemoration can be found across the near thirty other separate events or exhibitions held across the United States to coincide with the centenary of the declaration of war. These events were sponsored or supported by the Centennial Commission or its state affiliates and served to remind the general public of the war’s significance within the context of the 20th century. They ranged from small-scale local displays and exhibitions to large-scale exhibitions developed for national institutions. For example, the Saint Lawrence County Historical Association in Canton, Upstate New York, held an exhibition of propaganda posters to mark the centenary from April 2017, Come On! Posters and Portraits of World War I. The display engaged visitors in the methods used to rally support for the cause of the war. It also provided photographs of local servicemen who remained unidentified, and visitors were encouraged to engage and research the names using family knowledge or work on local history. Such connections between site-specific stories and national history provide vivid points of remembrance for this apparently forgotten war. They are also a means to establish a shared narrative and meaning of the war.

This was also present in the exhibition, From Flying Aces to Army Boots: WWI and the Chattahoochee Valley, which was displayed at the Columbus Museum, in Columbus, Georgia, from March to August 2017.[9] This wide-ranging display included voices from all sections of society in the Chattahoochee Valley, from the outset of the war in 1914 to the responses of local people to the announcement of peace and the signing of the Versailles Treaty in 1919. By focusing on the varied experience of the conflict and connecting the local with the national effort, the remembrance of the war as a shared narrative was asserted. The conflict was specifically framed within a wider narrative of the “American century.” This specific idea was present in a number of displays in museums and archives, such as World War: America and the Creation of a Superpower, which was held in the Sullivan Museum & History Center, Norwich, Vermont, from August 2016 to June 2017. The display of uniforms, medals, propaganda and trench art to represent the war on the battlefield and the home front was part of a wider exploration of the United States in the world during the modern era. The exhibition also marked the 75th anniversary of the Second World War and brought the events of 1917-1918 into association with the well-established place of the later conflict within national memory. Through embedding the First World War into the story of the “American Century” and aligning the concerns of the two global conflagrations, the remembrance of the entry of the nation into war in 1917 was cemented as part of the national story.

Some exhibitions offered a critical exploration of the experience of the United States during the war years. Arlington National Cemetery held an exhibition in their Welcome Centre from April 2017 to November 2018 on the war with displays on the racial and gender divisions within the country. Similarly, the exhibition Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I, located in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress from April to December 2017, explored the social divisions and repression of civil rights that emerged during the conflict. The Museum of the City of New York in Manhattan exhibited Posters and Patriotism: Selling World War I in New York from April to October 2017, which also assessed the war as a divisive part of the nation’s history.[10] The exhibition explored how the city became a battleground of identities right from the outbreak of the conflict in 1914.[11] The array of posters, magazines and political pamphlets emphasised the growing level of control over dissenting voices and the promotion of a singular American identity in a diverse, immigrant city. However, in this exploration of division and dissent, these exhibitions also served to normalise the place of the war in the national narrative, as part of the wider struggles for representation and equality.

A Spirit of Sacrifice: New York State in the First World War, exhibited at the New York State Museum in Albany from April 2017 to June 2018, provided a means for this new memory of the war to be engaged with by the wider American public. This display, which featured extensive archival collections, asked visitors to consider how those from New York contributed to the war effort and elevated the country onto the global stage. The same concentration of remembrance existed in the exhibits housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D. C. Two exhibitions were arranged for the centenary of the entry of the United States into the war, John J. Pershing and World War I 1917-1918 and Advertising War: Selling Americans on WWI.[12] The first of these displays focused on the way Americans responded to the call to service, whilst Advertising War examined the way in which American citizens were informed of the war. What was remembered here is the significance of the war in the lives of Americans and their contribution to the formation of the significant events of the 20th century.

The same issues were present in the National Postal Museum in Washington, D. C.[13] In their exhibition, My Fellow Soldiers Letters from World War I, which ran from April 2017 to November 2018, the connections maintained by individuals and families through letters are explored. The significance of participation was key to this display, as the endeavours of citizens revealed the local and national importance of the war. A number of exhibitions and displays have engaged with these issues to reveal other obscured or forgotten histories of the conflict, especially the experience of African Americans. Faced with racial violence at home and subject to segregation in the army, museums and galleries have sought to reveal and explore how all citizens participated. For example, Citizen Soldiers: Worcester in World War I was displayed at the Worcester Historical Museum in February 2018 in Worcester, Massachusetts. The exhibition focused on the participation of African Americans from the area, in recognition that this was a conflict that was faced by everyone within the United States. Similarly, the New York State Office of General Services’ 2018-2019 exhibition in Albany, Their Glory Can Never Fade: The Legacy of the Harlem Hellfighters, extolled the achievements of the African American soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment who fought with distinction on the Western Front.

Addressing the absence of historical memory has been an important part of shaping the response to the centenary of the First World War. This has been incorporated in the new American memory of the conflict through a focus on the shared experience of shaping the “American Century”. During the marking of the centenary of the entry of the United States into the war, a new engagement with the conflict could be witnessed. Across the nation, exhibitions and displays worked with the notion that the First World War set the agenda for the “American Century”. Whilst the war had never been forgotten, the programme set out by the Centennial Commission from 2013 culminated in national recognition in April 2017 as the war was placed in a wider scheme of remembering the events of the 20th century.

Using the Modern American Memory of the First World War↑

A number of initiatives designed to maintain the place of the First World War within the public consciousness in the United States were launched from 2014 onwards. This work was undertaken or supported by the Centennial Commission as well as other organisations and included sets of commemorative coins by the U.S. Mint, schemes to preserve and protect war memorials and the creation of a national war memorial in Washington, D. C. The long-running debate regarding a memorial in the capital was brought to a head by the creation of the Centennial Commission and the advent of the centenary, which focused the attention of politicians and planners. Whilst the idea had been under discussion since the 2000s, the National World War I Memorial was brought into formal existence in 2014 when legislation permitting a monument in Pershing Park was signed by President Barack Obama. The design for the site was chosen in 2016. The monument, entitled The Weight of Sacrifice, echoes the themes of the new American memory of the war in both its title and its appearance. It is a public park, where every square foot of soil represents one of the 116,516 Americans lost during the war, enclosed by a memorial wall detailed with texts and images that represent service.[14] The memorial complex is designed to firmly embed the memory of the war within American public life.

However, it is not through memorials and monuments alone that social memory is formed and maintained. An attempt to create a new memory of the conflict cannot be achieved through a top-down programme of engagement. Social memory must be incorporated into lives, habits and identities if it is to be accepted. Memory must be useful for it to be present within society. A number of television programmes engaged with this process during 2017, for example the documentary series The Great War, which was broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service as part of the “American Experience” series in three parts on 10-12 April. Whilst exploring the difficult and divided experiences of the war, the series emphasised the significance of the conflict for American society. This was conveyed through a series of contrasts: fighting for liberty in Europe whilst segregation and disenfranchisement of African Americans continued; decrying the brutality of the enemy despite the racial violence and lynchings taking place in southern states; and proclaiming democracy as the cause to fight for as repressive legislation was enacted to monitor civilians at home. As such, the war was used to discuss the wider history of American public life in the 20th century. The opening narrative of the first episode of the series stated: “All across the country, communities staged elaborate celebrations to send their men off to war. But underneath the calls for unity, Americans were deeply divided.”[15]

Audiences could recognise the struggles and issues that have sometimes been associated with the post-1945 world right at the outset of the 20th century. This use or deployment of the conflict to address contemporary concerns demonstrates an increasing “presence” of the war that was once regarded as forgotten. For example, the television broadcasting service Fox News described the events of 6 April 2017 as a testament to the place of the United States in the world:

Commentary in the editorials of the major metropolitan newspapers also reflected on how the war is useful for contemporary reflection in the United States.[17] Professor Michael Kazin, writing in the New York Times, indicated the transformative impact of the war:

The reference to contemporary issues within the United States is significant. The commemoration of the war in 2017 took place during an era when domestic and international issues were heavily debated. The election of Donald Trump as president in November 2016 brought debate about American identity and the role of the United States to the world stage. Television and media representation provided a chance to engage with the legacy and meaning of the First World War beyond the principle of the “American Century”. A demonstration of this utility could be seen in the midst of the commemorative activities in April 2017. As the legacy of the war was debated, news of military action in Syria by President Trump was released. This was compared, both supportively and critically, with the events of a century ago. The Times of San Diego remarked in an opinion piece on the “distant echoes” of the First World War in this military action.[19] Contrasting past and present in this manner indicates a presence and use of the war within wider cultural consciousness; this is an active use of social memory. Similarly, in a piece printed in the USA Today a few days before the centennial commemoration, the spectre of the First World War was raised as a means to critique the Trump presidency.[20] This could indicate the use of the new memory of the war within the United States; it is a process of memory that is active and engaged. Whilst the First World War has been cast as the formative part of the “American Century”, its memory is used socially and culturally to understand what that century means for the present day.

Conclusions↑

The activities associated with the centenary of the United States entering the First World War provided a means to engage with a history that had been neglected in the national narrative. The reasons for this apparent absence of the war within the public consciousness are complex. The events of the Second World War and the Vietnam War certainly dominate the understanding of America’s recent past. However, scholars have highlighted how the First World War was so divisive within the United States that forgetting the conflict might have served as a suitable response. However, as the centenaries of both the war itself and the participation of the United States in it began to be marked, an agenda to commemorate the conflict as the formative point of the “American Century” emerged at the federal level. This concern was reflected in the exhibitions and displays held to engage the public, as this “forgotten war” was brought into the national narrative. As the war was discussed and raised in the context of the centenary, another aspect of this remembrance emerged: connections and associations with the past were used to inform and understand contemporary military and political contexts. This represents the emergence of a new American memory of the First World War; a remembrance of the conflict not as an aspect of history but as a point of reflection.

Ross Wilson, University of Nottingham

Section Editor: Bruce Scates

Notes

- ↑ Bodnar, John: Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton 1992; Piehler, G. Kurt: Remembering War: The American Way, Washington 1995.

- ↑ Glassberg, David / Moore, J. Michael: Patriotism in Orange: The Memory of World War I in a Massachusetts Town, in: Bodnar, John (ed.): Bonds of Affection: Americans Define Their Patriotism, Princeton 1996, p. 189.

- ↑ Trout, Steven: On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010.

- ↑ H.R.6364 - World War I Centennial Commission Act, issued by Congress.gov, online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/6364 (retrieved: 25 March 2019).

- ↑ Introduction, issued by The United States World War One Centennial Commission, online: http://www.worldwar1centennial.org/about.html (retrieved: 15 July 2017).

- ↑ Neiberg, Michael S.: The Path to War: How the First World War Created Modern America, Oxford 2016; Zieger, Robert H.: America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience (Rowman & Littlefield 2000.

- ↑ In Sacrifice for Liberty and Peace: Centennial Commemoration of the U.S. Entry into World War I, issued by The United States World War One Centennial Commission, online: www.worldwar1centennial.org/sacrifice-about.html (retrieved: 25 March 2019).

- ↑ Isleib, Chris: Nationwide Events Commemorating U.S. Entry into World War I, issued by The United States World War One Centennial Commission, online: http://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/communicate/press-media/wwi-centennial-news/2112-nationwide-events-commemorating-u-s-entry-into-world-war-i.html (retrieved: 5 August 2017).

- ↑ From Flying Aces to Army Boots: WWI and the Chattahoochee Valley, issued by The Columbus Museum, online: www.columbusmuseum.com/exhibition/flying-aces-army-boots/ (retrieved: 13 August 2017).

- ↑ Posters and Patriotism: Selling World War I in New York, issued by the Museum of the City of New York, online: www.mcny.org/exhibition/posters-and-patriotism (retrieved: 12 August 2017).

- ↑ See Wilson, Ross: New York and the First World War: Shaping an American City, London 2014.

- ↑ Gen. John J. Pershing and World War I, 1917–1918, issued by The National Museum of American History, online: www.americanhistory.si.edu/exhibitions/pershing-world-war-I (retrieved: 15 July 2017); Advertising War: Selling Americans on WWI, issued by The National Museum of American History, online: www.americanhistory.si.edu/exhibitions/advertising-war (retrieved: 15 July 2017).

- ↑ My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from World War I, issued by the National Postal Museum, online: https://postalmuseum.si.edu/MyFellowSoldiers/ (retrieved: 25 March 2019).

- ↑ The Weight of Sacrifice, issued by The United States World War One Centennial Commission, online: http://www.worldwar1centennial.org/stage-ii-design-development/the-weight-of-sacrifice.html (retrieved: 12 November 2017).

- ↑ Ives, Stephen / Pollak, Amanda / Rapley, Rob: The Great War, United States 2017.

- ↑ Kopp, Jason: How World War I Changed the World Forever, issued by Fox News, online: www.foxnews.com/world/2017/04/06/how-world-war-changed-world-forever.html (retrieved: 12 July 2017).

- ↑ Will, G. F.: What World War I Unleashed in America, in: The Washington Post, 7 April 2017.

- ↑ Kazin, M.: Should America Have Entered World War I? in: New York Times, 6 April 2017.

- ↑ Novarro, Leonard: Distant Echoes of World War I in President Trump’s Strike on Syria, issued by Times of San Diego, online: https://timesofsandiego.com/opinion/2017/04/08/opinion-distant-echoes-of-world-war-i-in-president-trumps-strike-on-syria/ (retrieved: 25 March 2019).

- ↑ Hampson, R.: Trump and the War that Helped Make America Great in the First Place, in: USA Today, 5 April 2017.

Selected Bibliography

- Barbeau, Arthur E. / Henri, Florette: The unknown soldiers. Black American troops in World War I, Philadelphia 1974: Temple University Press.

- Bodnar, John E.: Remaking America. Public memory, commemoration, and patriotism in the twentieth century, Princeton; Oxford 1992: Princeton University Press.

- Budreau, Lisa M.: Bodies of war. World War I and the politics of commemoration in America, 1919-1933, New York 2010: New York University Press.

- Budreau, Lisa M.: The politics of remembrance. The Gold Star Mothers' pilgrimage and America's fading memory of the Great War, in: The Journal of Military History 72/2, 2008, pp. 371-411.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: The World War and American memory, in: Diplomatic History 38/4, 2014, pp. 727-736, doi:10.1093/dh/dhu037.

- Craig, Douglas: Commemoration in the United States. ‘The reason for fighting I never got straight’, in: Australian Journal of Political Science 50/3, 2015, pp. 568-575.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War, and the remaking of America, Baltimore 2001: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: The memory of the Great War in the African American community, in: Snell, Mark A. (ed.): Unknown soldiers. The American Expeditionary Forces in memory and remembrance, Kent 2008: Kent State University Press, pp. 60-79.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: Remembering the 'forgotten war'. American historiography on World War I, in: The Historian 78/3, 2016, pp. 439-468.

- Licursi, Kimberly J. Lamay: Remembering World War I in America, Lincoln; London 2018: University of Nebraska Press.

- Piehler, G. Kurt: Remembering war. The American way, Washington, D.C. 1995: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Seitz, David W.: World War I, mass death, and the birth of the modern US soldier. A rhetorical history, Lanham 2018: Lexington Books.

- Slotkin, Richard: Lost battalions. The Great War and the crisis of American nationality, New York 2005: H. Holt.

- Snell, Mark A. (ed.): Unknown soldiers. The American Expeditionary Forces in memory and remembrance, Kent 2008: Kent State University Press.

- Tooze, J. Adam: The deluge. The Great War and the remaking of the global order, 1916-1931, London; New York 2014: Allen Lane.

- Trout, Steven: On the battlefield of memory. The First World War and American remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010: University of Alabama Press.

- Wingate, Jennifer: Sculpting Doughboys. Memory, gender, and taste in America's World War I memorials, Burlington 2013: Ashgate.

- Zeiler, Thomas W. / Ekbladh, David K. / Montoya, Benjamin C. (eds.): Beyond 1917. The United States and the global legacies of the Great War, New York 2017: Oxford University Press.