Introduction↑

2017 marked the centenary of the British conquest of Palestine, but, more importantly, of the Balfour Declaration. These events prompted the publication of a large number of works dedicated to the analysis of the short and long-term legacy of the war in Palestine. Social historians like Salim Tamari focus on the war as a process that contributed to the remaking of Palestine, highlighting the trends that affected Palestinian society in the aftermath of the war.[1] An analysis of the long-term consequences of the war is the objective of works that – often – deal with the larger issue of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and attempt to search for patterns and trajectories, such as the introduction of ethnic violence or the reshaping of identities.[2] All these works agree that the British occupation of Palestine and the publication of the Balfour Declaration on 2 November 1917 had major repercussions for the following decades and up to the present day. The purpose of this article is not to question the legacy of these two aspects, but to look at how they were commemorated in 2017 in Israel and Palestine. Further, it will be suggested that these commemorations, rather than being part of a neutral narrative of remembrance, are an active part of the contemporary political discourse. In other words, commemoration is a major part of the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli conflict and both sides use it in an attempt to demonstrate their historical rights and grudges against each other.

The British Conquest of Palestine↑

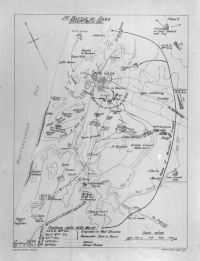

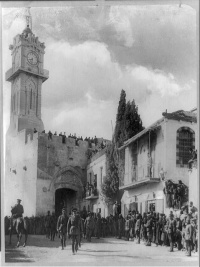

On 31 October 1917, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, led by General Edmund Allenby (1861-1936), attacked and captured Beersheva, a stronghold of the Yildirm force, which then allowed the British to finally take Gaza, on 6 November, and, later that year, Jerusalem. The battle, which was part of the third attempt to capture Gaza, was fought by a combination of British and ANZAC troops supported by mounted divisions.[3] Beersheva remained a quiet and largely Bedouin town until 1948, when it was captured by Israeli forces and rapidly turned into a Jewish city with the relocation of many Arab Jews from Egypt, Iraq and Morocco. 100 years later, Israel, together with the Australian and New Zealand governments, organized a massive international event commemorating the Battle of Beersheva. The program included a full re-enactment of the battle, which was televised and streamed online in its entirety.[4] The re-enactment was performed by Australian Light Horse Association riders, amateurs, and descendants of the Australian Mounted Division.[5] Though private involvement was inevitable, this was a state-sponsored event of transnational nature. Speeches were given by the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, and the Governor General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy. In different ways, they all invested time and effort in order to achieve a variety of goals at home and abroad. For instance, The Times of Israel suggested that:

Interestingly, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull added: “It did not create the state of Israel but enabled its creation... They defied history. They made history and with their courage they fulfilled history.”[7] What this narrative suggests is a connection between this battle, the war in general and the constitution of the State of Israel. However, as we saw earlier, Beersheva was an Arab town – Bir al Saba – and although there were no large demonstrations against these commemorative events, a few voices were raised in remembrance of a different reality. For example, Paul Daley, who in a column for The Guardian reminded us that:

Interestingly, despite the fact that the battle was fought by a large number of British soldiers – likely four times the number of ANZAC troops – the event was not officially commemorated by the British government. Since no statements have been released, we can only speculate that Prime Minister Theresa May chose to overlook this event in favour of the more complex but likely more politically satisfactory commemoration of the Balfour Declaration centenary. The Turkish side was going to be involved, yet due to the rather cold relations between the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, nothing materialized; in fact, as I witnessed the event first hand, I noticed that the Turkish flag at the old Ottoman train station had been removed. The centenary eventually passed quietly, and despite the media buzz, the event certainly had a longer impact on the Australian-New Zealand audience than on the local Israeli-Palestinian one. Locals enjoyed a day out of the ordinary and businesses benefitted from the large presence of foreigners in the city; what was missing from all of this was a genuine discussion of the war and its legacy.

The Balfour Declaration 100 Years Later↑

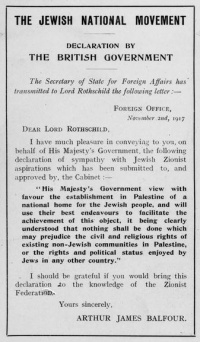

“Time to Party or Protest? Balfour Declaration Centenary is a Divisive Occasion”, Dina Kraft wrote in Haaretz on 30 October 2017, showing that the centenary commemoration of this event was going to be rather controversial.[9] The Balfour Declaration and its inclusion in the British Mandate, it can easily be argued, are the most important legacies of the war in Israel-Palestine. The British Prime Minister Theresa May, while celebrating the centennial of the declaration in the company of Jacob Rothschild, 4th Baron Rothschild and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, declared:

Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn, on the other hand, defined the Balfour Declaration as “an extremely confused document which did not enjoy universal support in the cabinet of the time, and indeed was opposed by some of the Jewish members of the cabinet because of its confusion.”[11] Although the British political spectrum exhibited division over the centenary, it is the academic and popular arenas that displayed the largest division over this event.

A coalition of Zionist Organizations sponsored an extensive program of events celebrating the Balfour Declaration. The website, http://celebratebalfour.org, represents the mouthpiece of this coalition, which aims to “ensure proper education and public recognition, within the English and Hebrew speaking public of Israel and the Diaspora, of the importance of the Balfour Declaration in the establishment of the State of Israel.”[12] Amongst the dozens of events supported, we should remember the organization of street parties in several Israeli cities, which were intended to popularize the celebration of the Balfour Declaration, and of a major academic symposium celebrating 100 years of this document. Other events were organized to criticize and demonstrate against, rather than celebrate, the document and its legacy. Thousands of Palestinians marched through the streets of Ramallah shouting slogans against British Prime Minister Theresa May and carrying signs suggesting the Balfour Declaration was the basis of the Palestinian Nakba of 1948: indeed, the very opposite of what was claimed by the Israeli official celebrations.[13] A critical discussion of the declaration and its legacy was arranged by the British Council in Palestine, the Educational Bookstore in Jerusalem and the Kenyon Institute, with the purpose of bringing together a number of scholars to discuss the document from multiple perspectives.[14] The National Palestinian Theatre in East Jerusalem was at capacity, including a large presence of Israeli scholars and international attendees.

Conclusion↑

In the end, the centenary passed quietly, despite many warning of a possible eruption of violence. Interestingly enough, on the day marking the 100 years since Allenby’s entrance into Jerusalem, no major events were organized. It is quite clear that the legacy of the war is still experienced on a daily basis, and the centenary did little towards a very much needed reassessment of that period and its long term repercussions. Though the memory of the war itself may become thinner and thinner, its legacy, in contrast, seems to be written in stone.

Roberto Mazza, University of Limerick

Section Editor: Bruce Scates

Notes

- ↑ Tamari, Salim: The Great War and the Remaking of Palestine, Oakland 2017.

- ↑ Campos, Michelle: Ottoman Brothers. Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine, Stanford 2011; Gribetz, Jonathan Marc: Defining Neighbors. Religion, Race and the Early Zionist-Arab Encounter, Princeton 2014; Klein, Menachem: Lives in Common. Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron, London 2014; Jacobson, Abigail / Naor, Moshe: Oriental Neighbors: Middle Eastern Jews and Arabs in Mandatory Palestine, Boston 2016.

- ↑ Bou, Jean: Australia’s Palestine Campaign, Canberra 2010, pp. 43-52. See also Erickson, Edward: Palestine the Ottoman Campaigns of 1914-1918, Barnsley 2016.

- ↑ For pictures see: Shihzur history: 100 shana le krav ha parashim she-shihrer et Beer Sheva [Historical re-enactment: 100 years since the cavalry battle that liberated Be'er Sheva], issued by Haredim 1, online: http://www.ch10.co.il/news/400148/#.WsdHii7wa70 (retrieved: 6 April 2018). The video is available at 100 Years of ANZAC, online: http://anzac.co.il/100years/%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%A9%D7%99/ (retrieved: 6 April 2018).

- ↑ Miller, Nick: ANZAC Light Horse Regiment Cavalry Charge at Beersheba Poised for Reenactment, issued by the Sydney Morning Herald, online: https://www.smh.com.au/world/anzac-light-regiment-cavalry-charge-at-beersheba-poised-for-reenactment-20171030-gzauh2.html (retrieved: 7 August 2018). See also Analysis, Diaries and Footage, issued by ABC, online: http://www.abc.net.au/ww1-anzac/beersheba/analysis-diaries-and-footage/ (retrieved: 17 October 2018).

- ↑ Ben Zion, Ilan: WWI Battle to be Re-enacted in Israel on Centennial of Anzac Defeat of Turks, issued by The Times of Israel, online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/wwi-battle-to-be-re-enacted-in-israel-on-centennial/ (retrieved: 5 April 2018).

- ↑ Commemorations in Israel, issued by Beersheba 100th Anniversary, online: http://beersheba100.com.au/events/israel.html (retrieved: 6 April 2018).

- ↑ Daley, Paul: Beersheba Centenary. Let's Remember that Story is not the Same as History, issued by the Guardian, online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/postcolonial-blog/2017/oct/30/beersheba-centenary-lets-remember-that-story-is-not-the-same-as-history (retrieved: 9 April 2018).

- ↑ Kraft, Dina: Time to Party or Protest? Balfour Declaration Centenary is a Divisive Occasion, issued by Haaretz, online: https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/.premium-time-to-party-or-protest-balfour-declaration-centenary-is-a-divisive-occasion-1.5461461 (retrieved: 12 April 2018).

- ↑ Full Text of May’s Speech at Balfour Declaration Centenary Dinner, issued by The Times of Israel, online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/full-text-of-mays-speech-at-balfour-declaration-centenary-dinner/ (retrieved: 12 April 2018).

- ↑ AlAhmad, Hussein: The Balfour Declaration Centenary, 2017. A Constructive Retrieval or an Odd Masquerade, issued by Al Jazeera, online: http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2017/10/balfour-declaration-centenary-2017-constructive-retrieval-odd-masquerade-171030103039272.html (retrieved: 12 April 2018).

- ↑ About, issued by the Balfour Centenary Committee, online: http://celebratebalfour.org/about/ (retrieved: 12 April 2018). Another set of events organized through another website – Balfour 100 http://www.balfour100.org/ (retrieved: 17 October 2018) – have been offered by a coalition of Christian-Zionist organizations throughout America and Israel.

- ↑ See Palestinians Protest against Balfour Declaration, issued by euronews, online: http://www.euronews.com/2017/11/02/palestine-balfour-declaration-israel-jerusalem (retrieved: 12 April 2018).

- ↑ Kenyoninstitute: Avi Shlaim. Britain and Palestine. From Balfour to May, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vx4-l_4iZF0&t=2506s (retrieved: 13 April 2018). This is the first video of the conference opened by Avi Shlaim.

Selected Bibliography

- Bou, Jean: Australia's Palestine campaign, Canberra 2010: Army History Unit.

- Gribetz, Jonathan Marc: Defining neighbors. Religion, race, and the early Zionist-Arab encounter, Princeton; Oxford 2014: Princeton University Press.

- Klein, Menachem: Lives in common. Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron, London 2014: Hurst & Company.

- Schneer, Jonathan: The Balfour Declaration. The origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict, London 2010: Bloomsbury.

- Tamari, Salim: The Great War and the remaking of Palestine, Oakland 2017: University of California Press.