Early Life↑

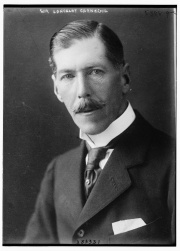

Lancelot Douglas Carnegie (1861-1933), British diplomat, son of James Carnegie, 9th Earl of Southesk (1827-1905) and Susan Catherine Mary Murray (1838-1915), was born in Edinburgh on 26 December 1861 and died in London on 15 October 1933.

Carnegie attended Eton College (Berkshire) and Oxford University. In 1887, he took on diplomatic functions in the Foreign Office. He passed through the diplomatic offices of Madrid, Petrograd and Beijing while carrying out his function as a diplomatic attaché and secretary of legation. In 1906, he was a counselor in the embassy in Vienna. In 1908, he was transferred to Paris, also as a counselor. There, he ascended to the position of minister plenipotentiary (1911-1913), participating as a British delegate in the International Sanitary Conference (1911-1912) and in the international committee for the resolution of the financial problems of the Balkan War (1913).

Arrival in Lisbon↑

In November 1913, he arrived in Lisbon to replace Minister Arthur Hardinge (1859-1933), whose diplomatic activities had been strongly criticized by the Portuguese Republican Party (also known as the Democratic Party). Carnegie introduced himself to the Portuguese president, Manuel Arriaga (1840-1917), with the credentials of envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary of the United Kingdom, issued on 22 October by George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936). Carnegie tried to restore the Anglo-Portuguese relationship to the desired atmosphere of cordiality, fading out the shadows of distrust, with the new republican regime, that hovered in the Foreign Office. In order to do so, he even praised the actions of the first radical government of Afonso Costa (1871-1937).

Portuguese Neutrality↑

When the controversy about the Portuguese belligerence in the Great War started, the English minister in Lisbon expressed his desire to keep Portugal out of the conflict, as he did not see any advantage in its intervention. However, that did not prevent him from regularly asking - alongside with Edward Grey (1862-1933) - for the collaboration of the Portuguese government with the Allied forces in Africa and Europe. This would imply, evidently, the violation of the duty of neutrality of the Portuguese state in that conflict. On 30 December 1915, he delivered a verbal note to Augusto Soares (1873-1954) asking the Portuguese government to requisition the German ships docked in Portuguese ports and charter them to England “as might be considered advisable”.[1] He also pointed out that the Italian government, “by Royal Decree, has reserved the right to requisition all foreign vessels in Italian ports and, without declaring war on Germany, has put this right into force as regards German vessels”.[2] Despite the suggestion of the British government, the Portuguese authorities would eventually participate in the war, something that put an end to the ambiguous international position maintained until then, which was imposed solely by the will of the British Foreign Office. On 10 March 1916, Lancelot Carnegie watched the Congress of the Republic declare war on Germany. When the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP) was already fighting in Flanders, Carnegie’s action in Lisbon was relevant to allay the apprehensions that the emergence of Sidónio Pais’ (1872-1918) dictatorship raised in the Foreign Office. During this historical period, he was the carrier of the message from George V that announced his intention of raising the diplomatic representation of England in Lisbon to the status of embassy. This project was concluded in 1924. Carnegie was then promoted to the rank of ambassador, a position that he held until 1928. In this year, he left Portugal “because of the established diplomatic practice”[3], as he had reached the age limit.

Conclusion↑

During his fifteen years in Portugal, there was consensus about Carnegie in national public opinion. He was recognized as one of the people responsible for the consolidation of the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. Carnegie followed Portuguese political and social life closely and travelled frequently across the national territory, to which he ascribed a large and unexplored touristic potential.

In Portugal, he was awarded with the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Santiago da Espada (1928) and the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Christ. In England, he received St. George’s Order (1916) and was vested as a Knight Commander of St. Michael’s, as a Knight of the Royal Victorian Order (1917), and as a Private Counselor of the United Kingdom (1924).

Bruno J. Navarro, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Section Editor: Ana Paula Pires

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Fraga, Luís Manuel Alves de: O fim da ambiguidade. A estratégia nacional portuguesa de 1914 a 1916 (The end of ambiguity. Portuguese national strategy from 1914 to 1916), Lisbon 2001: Universitária Editora.

- Morreu Sir Carnegie (Sir Carnegie died), in: Diário de Notícias, 16 October 1933, p. 1

- Silva, Armando Malheiro da: Sidónio e Sidonismo (Sidónio and Sidonism), Coimbra 2006: Imprensa de Universidade.

- Teixeira, Nuno Severiano: O poder e a guerra, 1914-1918. Objectivos nacionais e estratégias políticas na entrada de Portugal na Grande Guerra (Power and war, 1914-1918. National objectives and political strategies of Portugal’s participation in the Great War), Lisbon 1996: Editorial Estampa.

- Uma iniciativa patriótica (A patriotic initiative), in: O Século, 23 December 1923, p. 1

- Vincent-Smith, John D.: As relações políticas luso-britânicas, 1910-1916 (Luso-British political relations, 1910-1916), Lisbon 1975: Livros Horizonte.