Introduction↑

Much has already been written on memorializing the fallen and the culture of grief[1] during WWI and its immediate aftermath in the warring nations.[2] However, minimal foreign research has examined these issues with regard to Russia. Existing research analyses the (dis)continuity of the military-patriotic pre-revolutionary emigrant and Soviet memorial discourses.[3] This systematic neglect of mourning the fallen in WWI in Russian historiography stems from the artificial “covering-up” of WWI memories under the Soviet regime. The official Soviet narrative placed the October Revolution at the centre of Russian collective memory of the 20th century.

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate the transformation and continuation of funeral culture that took place under wartime conditions in Russia by studying the way death and the dead were viewed and by examining the phenomena loss, grief, mourning and burial.

Death at the Front: Imminent, Inevitable and Commonplace↑

Russia’s military losses in WWI – including battlefield deaths, deaths due to injuries, soldiers missing in action and soldiers who died in captivity – amounted to 3,300,000. A further 317,600 civilians were killed or died of war-related injuries.[4] Of the 17,600,000 mobilized Russian citizens, only 7,000,000 (1,400,000 regular soldiers and 5,600,000 on reserve) had any idea of what they would face.[5] Around 11,000,000 men of differing ages, ethnicities, religions, and social groups, with varying levels of education and life experience, found themselves face to face with war’s horror without any kind of psychological preparation. They suddenly found themselves permanently confronted with imminent death and had to choose between killing or being killed. They saw tens and hundreds of deaths each day and were forced to either bury their comrades, neighbours, relatives, citizens and fallen enemies or leave them unburied. They had to quickly adjust from regarding violent death as an extraordinary, strange and novel event (as opposed to a “normal” citizen’s death) to viewing military death as a normal, everyday mass event. This transition was discernible in the painful but necessary process of minimising funeral rites and death itself.

The Minimisation of Rituals↑

The first to experience the sense of loss were those in the trenches, who watched their brothers, fathers, sons, friends and neighbours be killed before their very eyes. Soldiers responded differently to the keen sense of loss, which could not be shared with relatives or close friends at home, either by incessantly sharing their sadness with colleagues[6] or by hardening their hearts and withdrawing into themselves.[7] They were deprived of an important and psychologically significant aspect of funeral culture: the chance to engage in traditional lamentation of the dead, to express grief to others and thus lighten the burden and receive consolation. This ritual was reduced to the utmost degree. The mourner was no longer a member of a grieving community, but a “man of war,” “the machinery of death,”[8] predestined to kill and be killed.

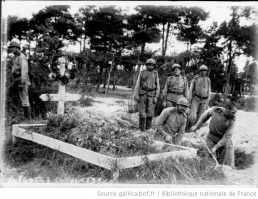

Another trauma was the lack of opportunity to observe, in full or in part, traditional funeral rites. Soldiers killed on the front were, more often than not, buried without the sanitary procedures deemed appropriate for a dead body, that is, without coffins and in mass graves. It was not uncommon to bury soldiers beneath a single wooden cross that effectively de-individualised the grave. At best, a hurried inscription showed the names of those buried. More often, the common graves were anonymous and undated.[9] Soldiers who had lost someone close to them tried to observe at least a minimal burial ceremony – if the body could not be buried in a coffin, then at least covering the face[10] and placing an individual cross with a name on the grave.[11] The ceremony’s religious side was also often minimised, signified only symbolically by reading prayers and making the sign of the cross.

Many non-combatants – both citizens and refugees living in the war zones – were also buried in the numerous mass graves and improvised military cemeteries lining the roads at the front. They died in the crossfire, victims of violence perpetrated by soldiers of all armies, or of disease and hunger. Roadside burials were also noted for their minimisation of rituals and mourning. Low crosses decorated with ribbons, flowers and scarlet rowan marked the graves. The interior of the grave was lined with stakes and fir branches and the corpses were placed inside without coffins. They were buried without tears and traditional lamentation. Victims of children’s cholera among the refugees were left unburied, with crosses made from fir branches pinned to their bodies and sometimes a wreath of wild flowers placed on their heads.[12]

The Minimisation of Feelings↑

In their reminiscences about the war, veterans frequently referred to soldiers’ rapidly acquired indifference to dead bodies, both their own side’s and the enemy’s. Recollected incidents were often akin to neglect and casual blasphemy. Crosses prepared for mass graves were used as kindling, potatoes were raked out between the corpses, mass graves were used as latrines.[13] Soldiers preferred not to notice the dead. Witnesses and military psychologists explained this indifference not so much as a “hardening of the soul” but rather as a defensive reaction to the extreme horror of everyday mass death and the thought of one’s own death. By distancing himself from others’ grief and rejecting thoughts of death, it was as if the soldier saved himself psychologically and disassociated himself from death, just as a medic described in his memoirs how he would habitually throw aside still-warm bodies in order to save the living.[14]

The civilian population of frontline areas, who found themselves at the very epicentre of the war, displayed a similar reaction to death and corpses, one that was clearly at odds with the psychological norm. As the poet Nikolai Tikhonov (1896-1979) put it later, “...children were not afraid of the dead.” One horrifying eyewitness testimony told of a group of eight- to twelve-year-old children who were playing with an Austrian soldier’s corpse. Laughing, they made a snowman, using the stiff corpse as its core.[15]

Woeful News and Mourning Ceremonies on the Home Front↑

Relatives learned of their loved ones’ death through letters from fellow soldiers from their region, the military authorities and newspapers.[16] The notification process for regular army deaths was badly organized. For example, on 18 August 1914, the head of the Kiev Military district announced that he was unable to give out information about the dead and the wounded and that he himself would draw upon the scant information from reports published from time to time in the “Russian Invalid” newspaper.[17] The newspaper cited information from the “Special Office of Records for the Gathering and Recording of Information Concerning Those Retired from Duty as a Result of Death and Injury, along with Those Servicemen Missing in Action Operating against Enemy Armies” and the “Special Department of the General Staff for the Gathering of Information on Losses in Armies in the Field.” This information was reprinted in other newspapers. However, these lists only included officers and not lower ranking soldiers. Lists of lower ranking soldiers killed, injured or missing in action were published separately in the “Bulletin of the St. Petersburg City Administration and the Capital’s Police” alphabetically by province.[18] Only later did regional journals start to publish the names of lower-ranking soldiers in several Russian provinces. However, the lists were often published with a considerable delay. For example, in some provinces, lists of those killed in 1914-1915 were only published in the spring and summer of 1917.[19]

Death on the Battlefield: Duty to the State or an Individual Act of Bravery↑

All the bereaved experienced grief for the dead, regardless of social class, ethnicity, religious persuasion or other differences. However, the death of relatives during the war was nonetheless perceived and discussed in different ways at home, depending on location and social status. This difference was particularly noticeable when comparing the “community” discourse of villagers and culturally similar urban lower classes with the official discourse generated by representatives of the educated upper and middle strata of urban society.

The peasant family and community traditionally saw soldiers off to war as if to certain death. In the peasant’s perception, mourning preceded death itself. The women’s laments reflected the belief that the one leaving would not return. Departing peasant soldiers assumed the same, resigned to the expected “hour of death in a foreign land.”[20] It did not occur either to those who left or to those seeing them off to resist this “fate.” Death in war was regarded as one’s duty, like the work of a ploughman.[21]

Despite the fact that all prior wars had demanded the bloodiest sacrifice from the rural population, wartime death was nonetheless experienced as the most flagrant violation of a normal, natural death in traditional peasant culture.[22] Those who had died a “good” and “natural” death and lay in the local village cemetery continued to be part of the peasant community, as they had made the transition to “ancestors.” They were visited on religiously and traditionally appropriate days, and were talked to and turned to in times of need. They protected the living. An untimely, “unnatural” death in a foreign country was considered a misfortune. Someone who died under such circumstances was no longer a member of his peasant community. Instead, he was torn away – he had not died well, nor had he found peace. Moreover, the unknown grave, and its distance from his home village, reduced the likelihood that his relatives might be able to visit it. Soldiers lamented this fact in their songs and letters: “No one will know the grave, / ... No friends will come, / ... No relatives will come, / ... And this grave in the spring, / ... will be overgrown with green grass.”[23] Peasant soldiers and their relatives were also frightened at the prospect of being buried without a religious ceremony, in a mass grave in unconsecrated ground (“the dead lie like firewood, two hundred to a hole,”[24] “climb into the hole and await burial there, like a dead horse”[25]) or at remaining unburied. Moreover, according to popular Christian and Muslim belief, the body of the deceased had to be intact at burial in order to be physically resurrected,[26] which was often extremely problematic due to war’s carnage.

The peasant mentality contrasted with the official patriotic and closely related urban discourses, in which death on the battlefield was portrayed as a heroic and noble deed. Family and friends’ grief and mourning were ennobled by feelings of pride. In the context of this discourse, a mother whose heart had been torn apart by grief was also supposed to be filled with pride at the fact that she had correctly and patriotically educated her children, who in turn had honestly and courageously fulfilled their duty.[27]

The Problem of Repatriating the Fallen and the Symbolic Splendour of Rituals↑

Unlike Europeans, who were already raising the question of “repatriating the fallen” to local cemeteries during the war years,[28] the majority of fallen Russians – especially peasant soldiers and the urban poor – had little chance of “returning home.” More often than not, they remained where they died, usually in mass graves. In contrast, many dead officers were laid to rest in urban cemeteries across Russia. The Moscow City Fraternal Cemetery, opened on 15 February 1915 at Elizaveta Feodorovna, Grand Duchess of Russia’s (1864-1918) initiative, was one of the few urban cemeteries. More than 18,000 victims and combatants, both from WWI and the political cataclysms that followed, were buried there.[29] Along with the majority of urban burial grounds, the Moscow City Fraternal Cemetery was destroyed during the Soviet era, as were the lists of the buried.

In the early months of the war, a few fallen officers’ bodies were ceremonially brought to St. Petersburg and Moscow. In the lavish funeral ceremonies, all the traditional religious, civil and military mourning rituals were diligently adhered to and attended by both relatives and friends, as well as officers, representatives of urban society, military and civilian officials, and sometimes even members of the tsarist family.

Urban funeral rites, especially as practised by representatives of the educated upper and middle classes, closely resembled those practised in Europe. However, they preserved many more traditional features than the European versions, which had been modernised, secularised and democratised in the 19th century and as a result had lost much of their pompous religious splendour. The modernisation of European rites was accompanied by the “rationalisation” of the burial business and paraphernalia. The process was also standardised through the use of electroplating for mass production of tombstones and of porcelain photographs of the deceased. The “industrialisation of death” in Europe culminated in the construction of modern mortuaries and crematoria and the practice of cremation, as well as the professionalization and specialisation of the funeral business.[30] In Russia, the influence of this process was minimal until the Bolsheviks came to power and was largely obstructed by the Orthodox Church.[31] Russian funeral rites were slowly modernised, retaining the solemnity and mystery of religious activities.

Mourning was symbolised by the presence of black and white. The church was covered with black cloth, laurel crosses with white flowers were laid across the coffins and saddled horses covered with black saddlecloths drew the funeral carriages carrying the coffins. Those attending mourning ceremonies and funerals wore black clothing. This was contrasted by the vestments of the Sisters of Charity, which stood out as bright spots in the black funeral procession and became an alternative to the passive expression of wartime mourning.[32] The white armbands and red crosses on the chests of mothers, widows, sisters and daughters who had become Sisters of Charity symbolised an active, engaged mourning. It was not without reason that women and girls of the tsarist family who worked in hospitals during the war also donned this attire. This act had not so much a practical significance in helping the wounded so much as a symbolic one, denoting the unity of the tsarist family with the people and their suffering and grief for the dead.

The ceremony for repatriated fallen officers normally began at the railway stations, where the bodies arrived in coffins. Wreaths and the dead officers’ military caps and sticks were placed on the coffin lids.[33] A litia was held at the station, with military honours bestowed by specially visiting military units. After this, the coffins, often accompanied by crowds numbering in the thousands, set off across the city to the final resting place, accompanied by the Funeral March. Clergy met the procession at the cemetery. After the litia, the liturgy for the dead at the cemetery church, and the last rites, the funeral procession headed for the grave, where the final litia was performed and “Eternal Memory” was sung. Then the coffin was lowered into the grave to the sound of the special military unit’s bugle. Volleys were fired when the first clods of earth fell on the coffin lid.[34] If the body of a fallen officer was to be buried in his home city or town and was only passing through St. Petersburg or Moscow, he would be honoured along the way.[35]

The repatriation of the fallen was, more often than not, carried out by their co-servicemen[36] or relatives and friends either at the front[37] or at home who had the sufficient means, time, strength and connections. Indeed, many liturgies and requiems for the dead that were performed in the two capitals and other Russian cities were named for the officers and all the unnamed “lower ranks who fell in battle with them” and were performed in absentia, without the bodies of those mourned. In August 1914, a memorial service was held in a Moscow church for two fallen officers in the absence of their parents and one of the widows who had left “for the theatre of military action in order to find the bodies of the deceased and bring them to Moscow for burial.”[38] In the course of a twelve-day journey to East Prussia, the relatives found the brothers’ graves, disinterred them and took them back to Moscow.[39] However, this was a well-known influential family who had the means and connections to undertake this onerous mission.

Most of the fallen who were of lower rank, and even many officers, whose relatives were not able to undertake such truly Herculean efforts to seek out, exhume and transport the bodies back to their homeland, were buried in individual and mass graves, sometimes named and often not, where they fell. Their families could pay their last respects only remotely, by way of religious rites, prayers at home and requiem services held in churches. Contemporaries noted the unprecedented number of worshippers in churches, an intensified religiousness, increased sales of candles and serving of holy bread, and rising demand for services for the dead.[40]

There is a clear continuity between the pre-war period and the funeral and mourning culture during WWI, both in general and in the various manifestations in the different groups of the population. The war highlighted and exacerbated glaring disparities in funeral rites between the battlefields and the home front. Given the conditions of military action, elements of ritual culture were minimised and vulgarised at the front. In contrast, this emotional and practical deficit of attention to the fallen was symbolically compensated for at home by a host of sumptuous funeral rites. These rites served as a proxy for the entire nation’s mourning and honouring the memory of the fallen.

This contradictory tradition of mourning and the emergence of the cult of WWI graves as “places of memory” was artificially brought to a halt by the Revolution of 1917 and the dramatic events that followed. These events transformed the way WWI was remembered. Russia found itself cut off from the modern European tradition of mourning those killed in battle, which was designed to heal the collective and individual traumas of warring nations. On the contrary, soldiers’ graves were deprived of state and social care and were not preserved. In post-revolutionary Russia there were practically no monuments or memorials to the fallen in WWI, and mourning them did not develop as a tradition. New traumas, caused by the mass deaths during the Revolution and Civil War, were piled upon the unassuageable collective and individual traumas from WWI that had not gone through the healing cleansing of national mourning.

However, the mourning patterns themselves that were developed during WWI did not completely end with the onset of the Revolution. Indeed, the continuity between pre-revolutionary and Soviet cultures of mourning and burial are clear. For example, during the Revolution and Civil War, which were also accompanied by mass deaths, the minimisation and secularisation of funeral rites practised on the front lines during WWI became the norm and were extended across the whole of Russia. The interrupted tradition of the stately honouring of the memories of the fallen in WWI was, in a revamped form, appropriated and put to use in the Soviet rituals honouring the “Red Heroes.”

Svetlana Iur’evna Malysheva, Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University

Section Editors: Boris Kolonit͡skiĭ; Nikolaus Katzer

Translator: Trevor Goronwy

Notes

- ↑ According to Jay Winter, “Grief is a state of mind; bereavement a condition. Both are mediated by mourning, a set of acts and gestures through which survivors express grief and pass through stages of bereavement.” See: Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: The Great War and Modern Memory, New York et al. 1975; Mosse, George: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, New York 1990; Hynes, Samuel: A War Imagined. The First World War and English Culture, New York 1991; Cork, Richard: A Bitter Truth. Avant-Garde Art and the Great War, New Haven 1994; Winter, Sites of Memory 1995; inter alia.

- ↑ Cohen, Aaron J.: “Oh, That!” Myth, Memory, and the First World War in the Russian Emigration and the Soviet Union, in: Slavic Review 62/1 (2003), pp. 69-86; Petrone, Karen: The Great War in Russian Memory, Bloomington 2011; inter alia.

- ↑ Stepanov, A.I.: Obshchie demograficheskie poteri naseleniia Rossii v period Pervoi mirovoi voiny [Overall Demographic Losses of the Russian Population in the Period of the First World War], in: Pervaia mirovaia voina: Prolog XX veka. Moscow 1999, pp. 478ff; Liudskie poteri v khode Pervoi mirovoi voiny [Casualties of the First World War], in: Naselenie Rossii v XX veke, volume 1, Moscow 2000, pp. 78f.

- ↑ Liudskie poteri v khode Pervoi mirovoi voiny [Casualties of the First World War], in: Naselenie Rossii v XX veke 2000, p. 80.

- ↑ A participant in the war recalled a young lieutenant who saw his brother wounded by shrapnel, and he died in his arms. A few weeks later the lieutenant would constantly return to this theme in conversation with his colleagues, apologetically repeating "I can’t forget it, I still can’t get used to it," and would hear in response the indifferent consolation of his comrades: "Get used to it," an artilleryman said to him, yawning. "In war you get used to everything." See: Voitolovskii, L.N.: Po sledam voiny. Pokhodnye zapiski 1914-1917, Moscow et al. 1931, pp. 112f.

- ↑ "The Austrians killed his brother-in-arms before his very eyes. His heart grew cold.... He became like a wild animal....” See: Fedorchenko, S.: Narod na voine [The People at War], Moscow 1990, p. 31.

- ↑ Voitolovskii, Po sledam voiny 1931, p. 94.

- ↑ "Buried here are fifty-six members of the Kamenets regiment … Buried here are soldiers of the Voronezh regiment.” See: Ibid. p. 315.

- ↑ "We wanted to make a coffin.... But how are you going to do that.... We lowered [the body] into the ground and at least covered his face with a handkerchief.... you don’t want dirt on the face...” See: Ibid. p. 113.

- ↑ "They killed my brother, but I didn’t know about it. I got to the detachment and asked - he’d been killed.... I went to look for him and they told me he was in a mass grave. I made a cross, made up a poem: “Sleep, my old brother, / Here I am, your little brother, / on behalf of your father and neighbours, / I am sent to bow to you.” See: Fedorchenko, Narod na voine [The People at War] 1990, p. 37.

- ↑ Voitolovskii, Po sledam voiny 1931, pp. 495, 503f.

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 46, 125, 127.

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 108, 125, 345.

- ↑ Sal’nikova, A.A.: Rossiiskoe detstvo v XX veke. Istoriia, teoriia i praktika issledovaniia [Russian Childhood in the 20th Century. History, Theory, and the Practice of Research], Kazan’ 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ "Father reads us the paper / He wants to know about his son / The papers write about the army / And tears burst from the eyes./ That his son was killed in the Carpathians / They write the military order.” See: Nalepin, A. L. / Shcherbakova, O. Iu. (eds): Soldatskii pesennik [A Soldier's Songbook], in: the Russian archive Istoriia Otechestva v svidetel’stvakh i dokumentakh XVIII – XX vv., issue VI, Moscow 1995, p. 474.

- ↑ Russkoe slovo [The Russian Word], in: Russkii Invalid, 19 August (1 September) 1914.

- ↑ On 25 November 1914, the sixth list of names was published – for the Vitebsk, Vladimir, Volhynian, Viatka, and Grodno governorates, the Don Voisko oblast’, and the Kaluga, Kiev, Kursk, Kutaisi, Livonia and Minsk governorates. See: Novoe Vremia, in: Bulletin of the St. Petersburg City Administration and the Capital’s Police, 26 November 1914.

- ↑ For example, lists of the killed, wounded and missing in 1914-1915 were published in the “Tambovskie gubernskie vedomosti” (The Tambov Province Gazette) from February to December 1917. See: Grigorov, A.I.: Name lists of those killed, wounded and missing of the lower ranks, natives of the province of Ryazan', published in the Ryazan' and Tambov provincial newspapers in 1917, in: History, Culture and Traditions of the Ryazan' Region, online: http://www.history-ryazan.ru/node/13049 (retrieved: 3 May 2012). Today, individual enthusiasts are creating online databases of those killed, injured and missing in action based on reports in provincial bulletins. See: Alekseev, Boris: Personal’naia istoriia, online: http://personalhistory.ru/1914-1918/htm (retrieved 5 March 2012).

- ↑ Voitolovskii, Po sledam voiny 1931, p. 8.

- ↑ Excerpt from a soldier’s song: "We ought not sow or plough / Or wave our threshers or scarves, / Oh, how duties have been fulfilled, / the graves are all overflowing with soldiers." See: Ibid p. 215.

- ↑ A peasant soldier wrote home: "Death is the natural end of the individual and of all, and war is a man-made destruction of entirely everything, not only people." See: Soldatskie pis’ma v gody mirovoi voiny (1915-1917), in: Krasnyi arkhiv 4-5/ 65-66 (1934), p. 142.

- ↑ Nalepin/Shcherbakova (eds.), Soldatskii pesennik [A Soldier's Songbook] 1995, p. 474.

- ↑ Maksimov, A. et al (eds.): Tsarskaia armiia v period voiny i Fevral’skoi revoliutsii. Materialy k izucheniiu istorii imperialisticheskoi i grazhdanskoi voiny [The Tsarist Army during the War and February Revolution. Materials for the Study of the History of the Imperialist and Civil Wars], Kazan’ 1932, p. 25.

- ↑ Voitolovskii, Po sledam voiny 1931, p. 30.

- ↑ See, for example: Merridale, Catherine: Steinerne Nächte. Leiden und Sterben in Russland, Munich 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Lines from the Emperor’s imperial rescript in the name of the Minister of War on 2 April 1916 - on the death in battle of three brothers Panayev, hussars of the Akhtyrsky Regiment. See: Sem’ia geroev, in: Ogonek, 24 April (May 7) 1916, p. 12.

- ↑ See: Winter, Sites of Memory 1995, pp. 15-28.

- ↑ Katagoshchina, M. V.: Materialy po istorii Pervoi mirovoi voiny v sobranii dokumentov Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeia [Materials on the First World War in the Collections of the State Historical Museum], in: Posledniaia voina Rossiiskoi imperii. Rossiia, mir nakanune, v khode i posle Pervoi mirovoi voiny po dokumentam rossiiskikh i zarubezhnikh arkhivov [The Last War of the Russian Empire. Russia and the World on the Eve, in the Course of, and After the First World War through Documents of Russian and Foreign Archives]: materials from the International Academic Conference September 7-8, 2004, Moscow 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ See, for example: Fischer, Norbert: Zur Geschichte der Trauerkultur in der Neuzeit. Kulturhistorische Skizzen zur Individualisierung, Säkularisierung und Technisierung des Totengedenkens, in: Herzog, Markwart (ed.): Totengedenken und Trauerkultur. Geschichte und Zukunft des Umgangs mit Verstorbenen, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 46-52.

- ↑ See: Merridale, Steinerne Nächte 2001, p. 186; Davies, Douglas J./Mathes, Lewis H. (eds.): Encyclopedia of Cremation, Aldershot 2005, pp. 369f.

- ↑ See, for example: Perevezenie na rodinu ostankov M.A. i A.A. Katkovykh [The Shipment of the Remains of M. A. and A. A. Katkov to the Motherland], in: Russkoe Slovo, 22 August (4 September) 1914.

- ↑ Pavshie na pole slavy [Those who Fell on the Field of Glory], in: Russkoe Slovo, 15 (28) August 1914.

- ↑ Pokhorony korneta S.N. Kolokol’tsova [The Funeral of Coronet S. N. Kolokol'tsov], in: Russkoe Slovo, 15 (28) August 1914.

- ↑ Perevezenie na rodinu ostankov M.A. i A.A. Katkovykh 1914 [The Shipment of the Remains of M. A. and A. A. Katkov to the Motherland].

- ↑ Cornet Kolokoltsov’s body was taken from the battlefield by his valet. See: Pokhorony korneta S.N. Kolokol’tsova.

- ↑ Cornet Lopukhin’s body was taken by his father - a commander in the Guards regiment. See: Perevezenie tela korneta Lopukhina, in: Russkoe Slovo, 15 (28) August 1914.

- ↑ Zaupokoinoe bogosluzhenie po M.A. i A.A. Katkovym [Funeral Service for M. A. and A. A. Katkov], in: Russkoe Slovo, 15 (28) August 1914.

- ↑ Kak nashli Katkovykh [How they found the Katkovs], in: Russkoe Slovo, 22 August (4 September) 1914.

- ↑ See: Shcherbinin, P.P.: Voennyi faktor v povsednevnoi zhizni russkoi zhenshchiny v XVIII – nachale XX v. [The Military Factor in the daily lives of Russian Women from the 18th to the beginning of the 20th centuries], Tambov 2004, pp. 252f.

Selected Bibliography

- Bryant, Clifton D. (ed.): Handbook of death and dying, Thousand Oaks 2003: Sage Publications.

- Capdevila, Luc / Voldman, Danièle: War dead. Western societies and the casualties of war, Edinburgh 2006: Edinburgh University Press.

- Cohen, Aaron J.: Oh, that! Myth, memory, and World War I in the Russian emigration and the Soviet Union, in: Slavic Review 62/1, 2003, pp. 69-86.

- Fedorchenko, Sofʹia / Trifonov, Nikolaii Alekseevich (eds.): Narod na voine (The people at war), Moscow 1990: Sov. pisatelʹ.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Kozlov, V. P. (ed.): Posledniaia voina Rossiiskoi imperii. Rossiia, mir nakanune, v khode i posle pervoi mirovoi voiny po dokumentam rossiiskikh i zarubezhnykh arkhivov (The last war of the Russian Empire. Russia and the world on the eve, in the course of, and after the First World War in documents of Russian and foreign archives), Moscow 2006: Nauka.

- Malʹkov, V. L: Pervaia mirovaia voina. Prolog XX veka (The First World War. A prologue to the 20th century), Moscow 1998: Nauka.

- Merridale, Catherine: Night of stone. Death and memory in twentieth century Russia, New York 2001: Viking.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Petrone, Karen: The Great War in Russian memory, Bloomington 2011: Illinois University Press.

- Porshneva, Olga S.: Krestʹiane, rabochie i soldaty Rossii nakanune i v gody Pervoi mirovoi voiny (Russian peasants, workers, and soldiers on the eve of and during the First World War), Moscow 2004: Rosspėn.

- Seniavskaia, E. S.: Psikhologiia voiny v XX veke. Istoricheskii opyt Rossii (The psychology of war in the 20th century. The historical experience of Russia), Moscow 1999: Rosspėn.

- Voitolovskii, L.: Po sledam voiny. Pokhodnye zapiski, 1914-1917 (In the wake of war. Campaign notes, 1914-1917), 2 volumes, Leningrad; Moscow 1931: Gos. izd-vo khudozh. lit-ry.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Wittman, Laura: The tomb of the unknown soldier. Modern mourning, and the reinvention of the mystical body, Toronto et al. 2011: University of Toronto Press.