Birth of an Aviator↑

From 1907 to 1909, Francesco Baracca (1888-1918) attended the Military Academy of Modena, and then the Cavalry Training School. On 15 July 1910, he was appointed as a second lieutenant in the prestigious 2nd Cavalry Regiment Piemonte Reale, garrisoned in Rome. Baracca was able to lead an active social life, including concerts, opera, dances, dinners, fox hunting, and love affairs. These amusements remained part of his “airman way of life”.

At the end of April 1912, Baracca arrived in Reims to attend flying school where he obtained his pilot’s licence. He enthusiastically wrote to his parents about flight, pilots and their way of life and code of conduct and honour, and Paris. He wrote a great number of letters to relatives, friends, and women all his life, but his main correspondent was his mother. He came back to Italy at the end of July 1912, and was immediately assigned to the flying detachments.

In spring 1915, the Italian army bought Nieuport 10 aircrafts to strengthen its weak aviation, and on 23 May (the day before the Italian declaration of war), Baracca arrived in Paris to be trained. He stayed near Paris for two months, and flew over the trenches, witnessing some aerial battles. He wrote enthusiastic tales about the sight of the frontline from the air, but was also astonished by the powerful equipment deployed.

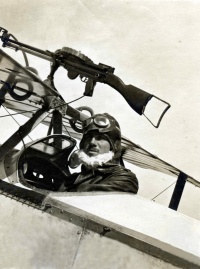

Ace Pilot↑

Baracca returned to Italy and was assigned to the 8th Nieuport Fighter Squadron, then the 1st Fighter Squadron, and, on 8 April 1916, the 71st Fighter. During the first months of war, Austrian planes were very difficult to stop, because Italian machine guns suffered from jamming. Baracca had to wait until 7 April 1916 to shoot down his first enemy plane. Subsequently, he gained thirty-three more victories.

On 11 February 1917, his fifth victory was confirmed. He became the first Italian ace, and his fame grew quickly. On 20 March 1917, he tested the SPAD S.VII, his first plane with a synchronized machine gun and propeller. On 6 June 1917, he became the leader of the 91st Fighter Squadron. On 6 September, he gained his nineteenth victory and was promoted to major by war merit. In the meantime, he began to fly the SPAD S.XIII.

On 24 October 1917, Austria-Hungary and Germany launched an offensive and the Italian army suffered a disastrous defeat in the Battle of Caporetto. During the following forty days, Baracca shot down ten planes. He had already received three silver medals and one bronze medal for military valour, and was now awarded a gold one.

Death↑

In the middle of June 1918, the Austrians launched their last offensive. Baracca and his men experienced, once again, a desperate and exhausting pace of fighting. On 19 June, at 6 p.m., Baracca took off to attack enemy infantry with his machine gun. A few minutes later, he was shot and crashed on the Montello hill. Only on 23 May were the Italians able to recover his body. Italy maintained that Baracca was killed by an infantry machine gun, while Austria gave the credit for the victory to Arnold Barwig (1896-1918), an observer officer on a Phönix C1 plane.

Baracca’s death caused a great stir both on the frontline and in the country, granting him an immediate apotheosis. He entered the national heroes’ empyrean straight away, playing a great role in the air force’s enormous rise in popularity.

Francesco Baracca was soon the cornerstone of aviation myths. Fascism quickly appropriated and nourished these myths, but they were able to outlive it and overcome the disastrous defeat of the Second World War. During the 1920s, the race car driver Enzo Ferrari (1898-1988) obtained, from Baracca’s family, permission to use his personal sign – the prancing horse – as a personal logo, and then for the famous sports car factory Ferrari.

Lugo devoted an interesting, modern and well-organized museum to Baracca, and most of his letters are held by the Risorgimento museum in Milan and the the Fabrizio Trisi library in Lugo.

Irene Guerrini, University of Genoa

Marco Pluviano, Collectif de Recherche International et de Débat sur la Guerre de 1914-1918 and Ligurian Institute for the History of the Resistance Movement and of the Contemporary Age

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Caffarena, Fabio: Dal fango al vento. Gli aviatori italiani dalle origini alla Grande Guerra, Turin 2010: Einaudi.

- Guerrini, Irene / Pluviano, Marco: Francesco Baracca. Una vita al volo. Guerra e privato di un mito dell'aviazione, Udine 2000: Gaspari.

- Lehmann, Eric: Le ali del potere. La propaganda aeronautica nell'Italia fascista, Turin 2010: Utet.

- Various authors: Francesco Baracca. Tra storia, mito e tecnologia. Atti della giornata di studi organizzata dal Comune di Lugo di Romagna e dallo Stato Maggiore Areonautica, Rome 2008: Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore Aeronautica.