Introduction↑

The First World War brought about important social, political, economic and cultural changes. The identities and relations between the sexes were also subjected to tension and remarkable transformations. It was the acceleration of a process that had begun in the late 19th century, when the “new woman” appeared. Endowed with culture and ambitions, active, and with a greater chance of individual achievement, this new person was the result of modernization. These changes came to fruition during the conflict due to women’s significant participation in social, intellectual and work spheres.

Women's work was, in fact, as important in industry as in the countryside and the services. Almost all production activity could continue without any major interruption. Female workers were particularly valued in the munitions factories and the industrial mobilization plants, key areas for a country at war. For some women, the departure of fathers, husbands and brothers meant looking for work, excessive fatigue, and more worries and responsibilities. Anxieties and new obligations also touched the lives of middle and upper class women who, with the outbreak of the conflict, had the opportunity to make a patriotic commitment. There were tens of thousands who participated in the so-called home front and, in a clear majority over men, used resources and creativity.

Naturally Italian women wondered about the reasons for the intervention: some were in favor of it and others were opposed to it, while a substantial proportion did not take a position, but, frightened and disorientated, awaited the course of events. A few months after the outbreak of the European war, women began to have a clearer idea of the situation and, aware of the burden of death and pain that would be the result, many of them reaffirmed their rejection of the country’s entry into the war. Women, whether peasants or workers, were incognizant of the purposes of the war but not indifferent to the fate of their men. They did not remain passive: they invaded the town halls with the intention of destroying draft cards and tried in every way they could to block the departure of those called to the front. Between the end of 1916 and August 1917 they took part in demonstrations against the lack of bread and rising cost of living, as well as in the spontaneous strikes for better working conditions and the conclusion of hostilities.[1] These protests were not always successful, but revealed a high degree of militancy that would have re-emerged after the war.

Apart from the opposition of ordinary people, often without political leadership, there was also the socialist, anarchist and anti-militarist opposition, but it only consisted of only a few militants, like the socialist Abigaille Zanetta (1875-1945). They maintained their consistent position of rejection of the war to the end. If in the summer of 1914 the neutralist front among the socialists seemed strong and compact, subsequent events led members and key figures to rethink the choices they had made.[2] For example, in December 1914 Anna Kuliscioff (1853-1925), a keen observer of international relations and their developments, considered Italy’s entry into the war inevitable. In her circle of friends, she spoke in favor of a "just war" and the necessity of Italy’s autonomy in the Mediterranean. On the whole, though, the militant women followed the Party’s lead, summed up in the formula “neither support nor sabotage” and took part in the charitable programs launched by the municipal councils which were headed by socialist mayors.[3]

The women who wanted Italy to enter the conflict were a nuclei of interventionists, loud despite being a minority, who gained the public stage by splitting the women's movement. Gradually a female front was formed, which tried to involve those who wanted to wait and see how events would develop. Imagining that sooner or later they would have to participate in the mobilization, some of them studied what had been organized in other countries.[4] The interventionist women harmonized with those who subscribed to "patriotic pacifism" advocated by the Nobel laureate for peace Teodoro Moneta (1833-1918). The most prominent activist of the group, Rosalia Gwiss Adami (1880-1930), called for Italy’s participation in the war in order to achieve national unification and defeat German imperialism.[5]

Feminism, however, was divided over the choice between neutrality and participation, how to translate the idea of loyalty to the homeland, and the relationship to be maintained with politics and the government’s choices. The suffragists were against the war, while Catholic women and less influential nuclei of women’s associations, with different nuances, showed themselves to be more receptive to patriotic appeals.

Although a lot remains to be done in order to give a detailed picture of Italian women’s experiences in wartime, it can be said that the effects of the conflict were also felt after it had ended. However, the significant changes to women’s identity as well as to the relations between the genders had no chance of becoming consolidated. Once the hostilities had ceased, the need to put aside the months of suffering and upheavals was accompanied by the need to normalize individuals’ lives in order to return to peace quickly. In this framework, the rise of Fascism can be interpreted as an attempt to restore order in the disorder caused by the conflict. This is a way to emphasize that the experience of war, with its accompanying myths, rituals and symbols, should be viewed and remembered as being all male.

Italian Women Confronted by the War↑

As had already happened in the warring nations, the Italian Government called on the people to mobilize. On 29 May 1915, urged citizens to help the combatants’ families the Prime Minister Antonio Salandra (1853-1931) through a letter sent to all the newspapers. The municipal authorities had the task of organizing, and partly financing, committees of civilian assistance throughout the country.[6] The cooperation that the authorities asked for and the readiness with which civilians responded stemmed from the belief that they were facing a heroic and short-lived conflict, which would end in victory.

Only six days after war had been declared against Austria, women's groups answered the call with patriotic enthusiasm and an enterprising spirit. Several of them began their own projects, others participated in those which, at the exhortation of the institutions, flourished everywhere. Generally remote from political commitments, these high-ranking women were traditionally involved in the world of charity. Ideologically close to the liberal sphere and in line with the government’s decisions, they tried to satisfy the many requests for aid.

With the participation of civilians, a home front which included a variety of motives began to take shape. There were quite a few instances of women's groups and individual women opposed to the war, but willing to cooperate. An example was the offer of help from “practical feminism”, conducted as a sign of solidarity with the wives, children and mothers in need of help after the departure of the men. The Women’s Union, the most representative association of this trend, led by Ersilia Majno Bronzini (1859-1933), offered its own network of contacts and services which had been tested over the years.[7] For some time, the representatives of practical feminism, who had been following an integration strategy in a state that had difficulty recognizing them, did not limit themselves to demanding rights and reforms. Through their project they sought to help those in trouble, looking for a home or a job, but the social work carried out by the militant women should have set an example for public institutions, been a stimulus to do just as much. In this context, the war represented an opportunity, for these women, to achieve at least two objectives: to be legitimized by the state itself as a model for social intervention, and to reach those still unaware of the struggle to obtain dignity and justice.

There were also the suffragists, who considered the right to vote in administrative and political elections, active and passive, the most effective weapon for being heard in a representative system. Following the example of their British and French sisters, Italian women used the war-time situation to try to achieve full citizenship. The Pro-Suffrage Committee of Milan, the most combatant and convinced of all, argued that the exemption from military service had until then been the legal justification for denying women the right to vote. The suffragists therefore decided to take part in the war effort. They established a relationship between the defence of the nation and the right to vote which, in their view, they would have achieved in exchange for support of their country. Also in this case, and after the defeats suffered by the movement, mobilization was deemed a useful strategy to integrate women in the body politic.

Italian Women in Favor of the War↑

The distinction between feminism and suffragism was obviously not so clear-cut. Many militants adhered to one or the other, more often than not to both, but the common denominator was the proximity to the peace movement that for decades had linked women to an international network for the exchange of ideas and undertaking of joint action. The abandonment of that perspective was neither immediate nor painless and matured during the first nine months of neutrality. The dramatic events which influenced choices and gave rise to second thoughts included the declarations of war that followed shortly afterwards and involved several countries; violations of international law and the invasion of neutral Belgium; the violence perpetrated against civilians and rapes committed by the soldiers of the occupying armies; and the mobilization in individual states which emphasized, above all, the “sacred reasons of the fatherland”.

Female interventionism, reflecting the broader interventionist front, began to call for Italy’s participation shortly after the outbreak of the European conflagration. Leading figures and small groups of agitators, among the women, with little impact on the women's movement, expressed the same positions as democratic interventionism. The irredentist Ernesta Battisti Bittanti (1871-1957), the wife of Cesare Battisti (1875-1916), a member of the Viennese parliament and future national hero, called for a war against Austria to liberate and reunify the regions under Austrian rule. The idea of a conflict in order to bring about the completion of the Risorgimento was shared by the Republican Adele Albani Tondi (1863-1939), the radical Beatrice Sacchi (1878-1931), and the feminist socialist Emilia Mariani (1854-1917), who all sided with France and Britain, parliamentary-democratic powers. Women anarchists and revolutionary syndicalists such as Maria Rygier (1885-1953) saw a road to revolution in the conflict. Some futuristic and socialist women, such as the art critic Margherita Sarfatti (1880-1961) and the teacher Regina Terruzzi (1862-1951), were also very enthusiastic about the idea of a regeneration, and left the party to follow Benito Mussolini (1883-1945). Finally, there were the women nationalists who, at first in favor of a common front with Austria and Germany, quickly sided with the countries of the Entente. A representative of this view was the lawyer Teresa Labriola (1873-1941), an active suffragist and the most committed to seeking entry into the war.[8]

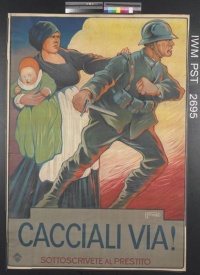

In this part of the women's movement there was therefore the same political and cultural fragmentation that was observed in the country, but the group of interventionist women appeared to be very determined. Engaged in propaganda activities, without excluding any form of social assistance, this numerically small sector had a considerable impact. In the long run, in fact, it managed to win over some of the uncertain women who were attracted by the myths of the Risorgimento, by the perspective of the "just war", by young people’s enthusiasm and the exploits of Gabriele D'Annunzio (1863-1938), which also inflamed male hearts.

However, during the period of neutrality and during the conflict, there were still doubts and amazing changes of position. While taking part in the action on the home front, some women continued to be uncertain about their own choices, but the anti-German sentiment of some was radicalized even before the defeat at Caporetto. On 24 October 1917, the breakthrough of the Italian lines caused unspeakable discouragement for everyone. The action of the home front was, by that time, concentrated on helping the second wave of refugees and propaganda for resistance.

Civilian and Health Mobilization↑

That women's participation in the war had different characteristics and purposes may be seen from the many efforts they organized, which should be examined more closely. While Italy was still neutral, one of the first issues to be addressed was that of assisting the tens of thousands of refugees, mainly from the northeastern borders. The municipality of Milan, given the proximity to the Austrian border, immediately put a number of measures into effect. All the political forces including members of practical feminism, social reformism and the liberal democratic part of the women's movement participated in the junta headed by the Socialist Emilio Caldara (1868-1942).

After the declaration of war on Austria, the policy of providing civilian, moral, and legal assistance as well as health care was mainly directed towards the soldiers and their families. Subsidies were handed out, home visits were organized, crèches and after-school care were set up, and hot meals were provided in soup kitchens. In order to enable the combatants’ female companions to access modest subsidies, wedding ceremonies were performed by proxy and procedures for the recognition of natural children were established. Women's associations and committees of civilian assistance set up workshops to make military clothing. Material was also distributed at home in order to make woolen vests and socks, antiparasitic camisoles and smokeless heaters to warm up food rations.

In Bologna in June 1915 the Countess Lina Cavazza (1886-?) organized the office for news to the families of land and sea forces following the French model. Of extraordinary importance, this service provided information about the fate of wounded or deceased soldiers, and was recognized by the state, which financed it. In order to operate the 8,400 offices there were 25,000 women volunteers, whoc worked in cooperation with military chaplains, Red Cross nurses and visitors.

In the healthcare sector there was an unprecedented organization of resources. Hospitals were set up and nurse-training courses were started everywhere. The most important body in this regard was the Italian Red Cross which, as early as May 1915, already had a small army of 4,000 volunteers. Courses were also held by the Samaritan School, the White Cross, the Green Cross, some local committees and patriotic associations such as the Associazione Trento e Trieste. Nevertheless, permission to assist the wounded in the hospitals at the front was only granted to 1,320 Red Cross nurses, whose body aspired to guarantee good training and trustworthiness.[9]

It was not always so. The crash courses which were subsequently organized quickly churned out thousands of nurses who encountered various difficulties. Opposed by the medical officers and poorly tolerated by the military High Command, they were gradually able to gain acceptance, but not all were able to overcome the hardships of life in the wards. Some had to contend with gangrene, frostbite, amputations, horrific wounds, mental disorders and diseases such as the influenza epidemic, dubbed “Spanish”, which decimated combatants, civilians and the nurses themselves. Others endured bombings and three of them became prisoners and ended up in the concentration camp of Katzenau.[10]

The 10,000 volunteer nurses were joined by the nursing nuns traditionally involved in patient care. The number of nurses was incomparably low when compared to the powerful French Red Cross with its 70,000 nurses and 10,000 hospital visitors. However, while failing to achieve the desired efficiency, the volunteers were important in local hospitals and in those behind the line of fire. The care they provided allowed the military to deal with unforeseen situations and emergencies. Their presence had a positive impact on the more than 1 million wounded soldiers. After the end of the conflict, the members of the "white army" continued to help some of the 452,000 disabled undergoing treatment and rehabilitation. Epitomizing dedication, sacrifice and goodness, the Red Cross nurse was the most exalted and honoured of all the female figures involved in the mobilization.

Forms of patriotic solidarity were also expressed by soldiers’ pen friends,[11] and the associations of Catholic women and of the Jewish communities. Moreover, the mobilization of Jewish and Catholic women took on different meanings, but in both cases there was a desire to feel part of the nation. The Catholic Women’s Union, while dismissing, as Catholics, responsibility for the intervention, decided to fulfill its duty.[12] As early as January 1915, members were invited to stand ready to organize religious assistance for the army and moral assistance for the combatants’ families. Portable altars, wheat and wine to celebrate Mass were sent to the front line and soldiers passing through train stations were offered rosaries and prayer books. Those at the front were sent woolen clothing as well as everyday objects, and charitable work was set up. The activity carried out by the Catholic Women’s Union was thus legitimized in the country and within the Catholic world, which had been in doubt, until then, about whether or not to recognize the presence of an autonomous and self-organized female body within its ranks. Behind the choice of Jewish women, there was, instead, a kind of gratitude towards the monarchy and the nation for the emancipation granted to the entire Jewish community. Most members saw the last stage of the integration process in the war, which would make them full citizens. For middle class Jews, participation in the war effort produced important changes. In particular, there was a loosening of family and community ties within which female action had traditionally taken place. They were thus able to act more freely and work with women of another faith in an environment that aimed at overcoming religious affiliation in favour of a humanitarian commitment.[13]

The World of Work↑

In all the countries involved in the conflict, the wartime economy gave women more job opportunities. In a short time there was a great experience of mobility, which was also due to the needs of the conflict and more benevolent attitudes towards work outside the home.[14] The fact that women, including young workers, clerical staff, bookkeepers and those involved in services, were working outside the home was justified in the name of patriotic mobilization. Thanks to the latter there were new roles in the workplace countering, in reality, the widespread belief that women were occupying the posts of those who had left for the front. The most emblematic case was the munitions industry where the women workers were assigned new tasks to the eventual satisfaction of the industrialists who had initially had some reservations. Generally, however, the female workforce was quite improvized and this reinforced the distrust of the workers who saw the “wartime women workers” as intruders.

In the cities, the wives, sisters and mothers of artisans and traders did their best to run shops and small businesses, but the home crafts and those related to agriculture continued to be the areas where the presence of women was most marked. Obviously, the work at home, which allowed mothers to scrape together a few pennies and look after the family, increased everywhere and consisted in preparing military clothing.[15]

In the countryside, after gloomy forecasts about yields, the great effort made by women, the elderly and children managed to meet the needs of the population and the army. To achieve these results the peasant women took on manifold activities, including livestock breeding. Despite the call to arms of the male workforce, the yield of the countryside did not suffer particular downturns thanks to the 2 million peasant women who did all the strenuous work normally entrusted to men.[16]

The arms and munitions industry and the industries of military clothing, public transport and the service sector, instead, gave employment to hundreds of thousands of women. Although precise data are not available for all the areas, 200,000 women worked in the war-time industries, 600,000 were involved in the packaging of military clothing and there were no less than 3,200 women tram drivers.[17]

Like the Red Cross nurses, the wartime women workers gained an unprecedented visibility. The women tram drivers, the postwomen and the women workers involved in the production of arms and munitions, known in France as munitionnettes, were presented by the propaganda as symbols of modernity and the war effort. The political press, concerned about the female invasion in all areas, undertook to stigmatize the "distortion" of women caused by the conflict and its requirements, and hoped for a quick return to normality.

Towards Peace↑

Taking into account their commitment, the variety of their activities and the duration of the conflict, women's participation in the general mobilization was important and timely. In fact, it helped to ensure the normal operation of the country’s civil and economic life. Without women’s help, the home front would have functioned less effectively: public opinion and observers said that they were aware of this and amazed by it. But what was the meaning of the experience of war for those who took part in it? What were the repercussions in a movement that after having supported the link between pacifism and feminism justified the conflict and came closer to nationalism?

The studies which are available all agree that in those years elements of emancipation were introduced in people who learned to rely on their own strength and experienced new forms of autonomy and freedom. However, these changes were of a temporary nature and the need to get back to peace without further disruption was stronger. It was necessary to reunite families after a long period of absence, prepare to welcome the prisoners, help the maimed to resume their lives, and deal with the pain of bereavement, as well as the deprivations and fears for a future that appeared full of uncertainty and difficulty.

In the collective imagination, the tasks performed by men were seen as being the most important and the representations of the figure of the heroic and brave male warrior were set against the mother's sacrificial act of giving her children to the country. The mass war which, contrary to hopes and expectations, had taken place in the hardships of the trenches, was a humbling experience for the majority of the combatants. The crushing military defeat of Caporetto and the anguish and suffering undergone during those long years influenced the veterans’ self-esteem. Restoring the male identity, which was going through a crisis, was one of the objectives of the return to peace.

The feminist and suffragist associations felt the effects of the rift between interventionist and neutralist women that was further aggravated. Practical feminism which, with its particular character, had tried to mitigate the consequences of the war, was involved in an increasingly non-judgmental way in the war effort and had difficulty in defending its original objectives. Despite the focus on the needs and problems of families, the women's movement as a whole failed to reach the female masses. Leaving aside the results obtained in helping the population, the involvement in mobilization as a strategy for gaining access to political, social and economic citizenship proved to be unsuccessful. Parliament in fact failed to pass the law on the right to vote and the post-war period revealed the negative attitude of a political class not prepared, in practical terms, to recognize women as an essential part of the nation.

The generational change and the presence of new players triggered by the mobilization changed the profile of feminism and of some of its theoretical assumptions. The most traditional area animated by liberal and aristocratic women was absorbed by the nationalist women who, little by little, took over the direction of the movement. Thus the leadership, previously ascribed to women teachers and socialist women workers – who, as they were neutralists, were considered unpatriotic and therefore marginalized – was undermined. A new group, formed by those who had been active in the Red Cross before the war, managed, however, to carve out a space in health care policy to which due attention was to be given. It was these women reformers who emphasized the need to train people as professional nurses and health visitors in order to carry out the projects of rehabilitation and repopulation of the country. In a way, the era of political rights was closing and that of social rights was opening.

However, apart from the statements of pride and the new forms of female leadership, public certificates, proven reliability and some small successes, such as law n. 1176 of 17 July 1919 on legal capacity, it can be said that on the whole Italian women drew meagre benefits from the war.

Stefania Bartoloni, University of Roma Tre

Section Editor: Nicola Labanca

Translator: Noor Giovanni Mazhar

Notes

- ↑ Riots, work stoppages, demonstrations and improvised political rallies were reported in different parts of the country. The protests against the high cost of living and the lack of bread turned into riots against the war, especially in Turin, where soldiers expressed their solidarity with the crowd. For an eye-witness account from a protagonist of those days, cf.: Noce, Teresa (Estella): Rivoluzionaria professionale, Milan 1974, p. 27. In more general terms, see: Spriano, Paolo: Storia di Torino operaia e socialista. Da De Amicis a Gramsci, Turin 1972, pp. 416-431; Procacci, Giovanna: Dalla rassegnazione alla rivolta. Mentalità e comportamenti popolari nella Grande Guerra, Rome 1999; Bianchi, Roberto: Il conflitto sociale e le proteste, in: Labanca, Nicola (ed.): Dizionario storico della prima guerra mondiale, Rome-Bari 2014, pp. 253-267.

- ↑ Casalini, Maria: I socialisti e le donne. Dalla “mobilitazione pacifista” alla smobilitazione postbellica, in «Italia contemporanea», 222 (2001), pp. 5-41.

- ↑ Ambrosoli, Luigi: Né aderire, né sabotare. 1915-1918, Milan 1961. Regarding the activities of the socialist muicipal councils, cf.: Onofri, Nazario Sauro: La grande guerra nella città rossa. Socialismo e reazione a Bologna dal 1914 al 1918, Milan 1966 and Punzo, Maurizio: La giunta Caldara. L’amministrazione comunale di Milano negli anni 1914-1920, Milan 1986.

- ↑ Among these there was also Margherita Sarfatti, an intellectual and socialist activist who became an interventionist. In January 1915 she went to Paris for two months to see at first-hand how the work had been organized there, cf.: Sarfatti, Margherita: La milizia femminile in Francia, Milan 1915.

- ↑ For a description of this activist: Pisa, Beatrice: Modelli e linguaggi del pacifismo femminile fra vecchia Europa e Nuovo Mondo: Rosalia Gwiss Adami e Jane Addams (1911-1919), in: Rossini, Daniela (ed.): Le americane. Donne e immagini di donne fra belle époque e fascismo, Rome 2008, pp. 55-100.

- ↑ Fava, Andrea: Assistenza e propaganda nel regime di guerra (1915-1918), in Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): Operai e contadini nella grande guerra, Bologna 1982, pp. 174-212; Soldani, Simonetta: La Grande guerra lontano dal fronte, in Mori, Giorgio (ed.): Storia d’Italia. Le regioni dall’Unità a oggi. La Toscana, Turin 1986, pp. 402-433; Staderini, Alessandra: Combattenti senza divisa. Roma nella grande guerra, Bologna 1995; Menozzi, Daniele/Procacci, Giovanna/Soldani, Simonetta (eds.): Un paese in guerra. La mobilitazione civile in Italia, Milan 2010.

- ↑ Regarding the work of the Women’s Union, see: Buttafuoco, Annarita: Le Mariuccine. Storia di un’istituzione laica. L’Asilo Mariuccia, Milan 1985.

- ↑ Regarding these figures and the role they played during the war see the respective biographies: Montesi, Barbara: Un’«anarchica monarchica». Vita di Maria Rygier (1885-1953), Naples 2013; Cannistraro Philip V.: Sullivan, Brian R.: Il Duce’s Other Woman, New York 1993; Falchi, Federica: L’itinerario politico di Regina Terruzzi. Dal mazzinianesimo al fascismo, Milan 2008; Taricone, Fiorenza: Teresa Labriola. Biografia politica di un’intellettuale tra Ottocento e Novecento, Milan 1994.

- ↑ For information about the Red Cross nurses and how this body was organized cf.: Bartoloni, Stefania (ed.): Donne al fronte. Le Infermiere Volontarie nella Grande Guerra, Rome 1998.

- ↑ They were Maria Andina, Maria Antonietta Clerici and Maria Concetta Chludzinska.

- ↑ Molinari, Augusta: La buona signora e i poveri soldati. Lettere a una madrina di guerra (1915-1918), Turin 1998.

- ↑ Dau Novelli, Cecilia: Società, chiesa e associazionismo femminile. L’Unione fra le donne cattoliche d’Italia, Roma 1988; Pisa, Beatrice: La guerra delle donne cattoliche (1908-1919), Percorsi Storici, 2 (2014), online: http://www.percorsistorici.it/component/content/article.html?layout=edit&id=109 (retrieved 28 May 2015).

- ↑ Miniati, Monica: Le “emancipate”. Le donne ebree in Italia nel XIX e XX secolo, Rome 2003.

- ↑ Curli, Barbara: Italiane al lavoro. 1914-1920, Venice 1998.

- ↑ Regarding this aspect Pisa, Beatrice: Un’azienda di Stato a domicilio: la confezione di indumenti militari durante la grande guerra, in Storia contemporanea, 6 (1989), pp. 953-1006.

- ↑ Soldani, Simonetta: Donne senza pace. Esperienze di lavoro, di lotta, di vita tra guerra e dopoguerra (1915-1920), in: Corti, Paola (ed.): Le donne nelle campagne italiane del Novecento, Annali Istituto Alcide Cervi, 13 (1991), pp. 13-57.

- ↑ Pagnotta, Grazia: Tranviere romane nelle due guerre, Rome 2001.

Selected Bibliography

- Bartoloni, Stefania: Italiane alla guerra. L'assistenza ai feriti 1915-1918, Venice 2003: Marsilio.

- Belzer, Allison Scardino: Women and the Great War. Femininity under fire in Italy, New York 2010: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bianchi, Bruna: Crescere in tempo di guerra. Il lavoro e la protesta dei ragazzi in Italia, 1915-1918, Venice 1995: Cafoscarina.

- Bravo, Anna (ed.): Donne e uomini nelle guerre mondiali, Rome 1991: Laterza.

- Buttafuoco, Annarita: Questioni di cittadinanza. Donne e diritti sociali nell'Italia liberale, Siena 1997: Protagon.

- Casalini, Maria: Anna Kuliscioff. La signora del socialismo italiano, Rome 2013: Editori riuniti University Press.

- Curli, Barbara: Italiane al lavoro, 1914-1920, Venice 1998: Marsilio.

- Giorgio, Michela De: Le Italiane dall'Unità a oggi. Modelli culturali e conportamenti sociali, Rome 1992: Laterza.

- Guidi, Laura (ed.): Vivere la guerra. Percorsi biografici e ruoli di genere tra Risorgimento e primo conflitto mondiale, Naples 2007: Clio Press.

- Lagorio, Francesca: Italian widows of the First World War, in: Coetzee, Frans / Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin (eds.): Authority, identity and the social history of the Great War, Providence 1995: Berghahn Books, pp. 175-198.

- Molinari, Augusta: Una patria per le donne. La mobilitazione femminile nella Grande Guerra, Bologna 2014: Il Mulino.

- Papa, Catia: Sotto altri cieli. L'Oltremare nel movimento femminile italiano (1870-1915), Rome 2009: Viella.

- Pisa, Beatrice: La mobilitazione civile e politica delle italiane nella Grande Guerra, in: Giornale di storia contemporanea 2, December 2001, pp. 79-103.

- Procacci, Giovanna: Warfare-Welfare. Intervento dello Stato e diritti dei cittadini (1914-1918), Rome 2013: Carocci.

- Schiavon, Emma: Interventiste nella grande guerra. Assistenza, propaganda, lotta per i diritti a Milano e in Italia (1911-1919), Milan 2015: Mondadori Education.

- Staderini, Alessandra: Le forniture militari a Roma (1915-1918), in: Storia contemporanea 2, 1990, pp. 323-346.

- Willson, Perry: Italiane. Biografia del Novecento, Rome; Bari 2011: Laterza.