Introduction↑

Three motives shaped the Danish economy during the Great War. At the root lay short supply due to reduced imports. Firstly, it caused direct disturbance of the economic flow. Secondly, it stimulated inflation, as idle money chased a limited amount of goods. Thirdly, depleted stocks of real capital and materials reduced productivity, and boosted speculation and cheating. However, while challenges presented themselves as early as August 1914, they took more than two years to develop into a serious economic downturn.

A strongly enhanced state regulation was successful insofar as it was able to redress social imbalances and keep the wheels in motion. Nevertheless, by 1918, business was weary of regulation, unemployment was high, and worker militancy was on the rise. The need for reinstating market forces as the core institution of economic life was now acknowledged in all quarters, although reluctantly by social-liberals and Labour who were, respectively, governing and supportive party. Nonetheless, the experience of these abnormal years became instrumental in shaping economic and social policy and forms of governance, especially in times of crisis but even under prosperity.

The most comprehensive account of Denmark’s economy during the First World War is still Einar Cohn’s (1885-1969) work from 1928,[1] of which an abridged version is available in English (Cohn 1930).[2] Even earlier, in 1921, Johannes Dalhoff (1880-1951)[3] had summarized events on the labour market. Svend Aage Hansen (1919-2009)[4] in his 1974 magisterial work on economic growth in Denmark included a brief analysis of the most important tendencies of the war years. With Ingrid Henriksen, Hansen has also produced a broader survey focusing on social developments depicted against an economic background.[5] In a collective work on Danish monetary history, Erling Olsen (1927-2011)[6] provided a discussion of how the often difficult and controversial monetary affairs of the time were handled. A major work of recent years is by Kasper Elmquist Jørgensen,[7] who assembled a number of studies with the interplay between state and business as the unifying theme. Steen Andersen and Kurt Jacobsen [8] operate in the same area, with special reference to Alexander Foss (1858-1925), an industrialist who played important roles in both domestic regulation policy and bilateral trade talks. A recommendable overall introduction to Denmark and the First World War is Carsten Due-Nielsen's 1985 article in the Scandinavian Journal of History.[9]

The present survey begins with the impact of the war as such, followed by a short evaluation of economic growth from 1910 to 1929. The next two sections deal, respectively, with economic regulation and the labour market. Subsequently, foreign economic relations and their political setting are discussed. Brief mention is made of monetary and financial tendencies before the conclusive section on post-war development and the longer-term significance of the regulative and redistributive measures taken in the years 1914 to 1918.

Population and Territory↑

On the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, a so-called “defence force” was convened to manifest the willingness of the Danish state to enforce its neutrality and sovereignty. Even at a low level of alert, the summoning of the older conscripts was costly. Besides net loss of production, there were expenses incurred in running the military outfits and securing the livelihood of the married men’s families. The force was downsized as direct Danish involvement in the war became improbable.

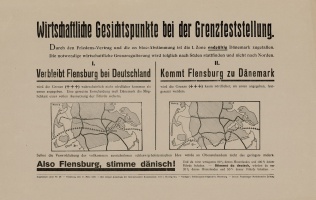

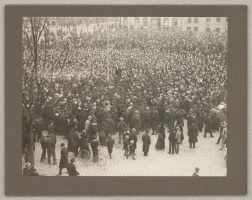

In a Danish context, the single most important economic event resulting from the First World War was the reunion of Northern Schleswig with Denmark. After the incorporation of the former duchies into the German Empire, the Danish-speaking minority immediately south of the border felt alienated, and in the Kingdom of Denmark, the idea of an unjust separation was strong as well. In 1920, following a referendum, 165,000 people, and the territory they inhabited, were transferred from the German Reich to the Kingdom of Denmark.

Practically no military operations took place in Danish national space. However, casualties occurred by the thousands among the Danish-speaking male population of Schleswig who at the time were German citizens. Ex-servicemen of that group, some of them wounded or traumatized, would shortly after the war change their nationality to Danish. Two hundred and seventy-five Danish registered merchant vessels were sunk in international waters, causing the loss of about 700 sailors’ lives.

Aggregate Economic Output↑

With a 5 percent rise in per capita GDP, compared to 1913, 1914 was a remarkably prosperous year for Denmark. The surge in economic activity was export-driven, as demand from belligerent nations shifted upwards, especially in agricultural produce. Four years dominated by negative growth followed, due to shortage of imported input commodities, most notably coal and fertilizers. The year 1919 saw a remarkable recovery, and by 1922 – after a crisis-ridden 1921 – GDP/c had definitely risen above the pre-war level.

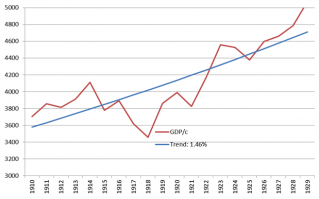

In a middle-term perspective (1910-1929), an estimated growth rate of 1.46 percent p.a. suggests that the delay caused by the war was not very serious (see figure 1). It is equally obvious though, that 1917 and 1918 were bad years, significantly below trend values. Other neutral countries in the region exhibit a similar structural pattern. However, the years of recession were milder in Norway. Sweden’s experience over the war years was more comparable to that of Denmark, but Sweden as well as Norway enjoyed higher growth 1910-1929. Both countries, on the other hand, were on a lower income level than Denmark, so a catch-up process unconnected with wartime events may have been under way. The Netherlands, however, were on the same income level as Denmark before the war. Its economy recovered faster and grew more vigorously during the 1920s. Relatively speaking, then, Denmark did not fare too well in economic terms during and after the war.

Economic Regulation↑

A central issue in August 1914 was the steady supply of household staples and other products essential to the economy. Extreme price rises would jeopardize household budgets and thereby basic material welfare. The threat seemed urgent, as belligerent nations mobilized available resources for their own purposes. Hence, the Danish government set up a special permanent commission of twelve members with ample powers to make inquiries and recommend measures to procure and distribute goods, if necessary by expropriation. The commission was also entrusted with the task of suggesting export prohibition and/or state-imposed maximum prices. The goods in question were defined as “foodstuffs and merchandise that society must by necessity have at its disposal”,[10] so it was a wide mandate.

The commission was made up of leaders from business organizations and labour unions; active businessmen from several fields; an economics professor; the mayor of Copenhagen; the commissary general; and a civil servant of the Ministry of the Interior, under which the commission belonged.[11] By virtue of its broad composition, combining specific expertise with representation of various social interests, the members were successful in getting things done. Nevertheless, while seeking collaboration they also fended for their own group.

Even before the commission was established, on 6 August, the government introduced an export embargo on foodstuffs, grain and grain products, potatoes and flour; gold and silver; fuels and lubricants; weapons, ammunition and explosives; cables; motor vehicles; wood and steel; and instruments, machines and appliances for the manufacture of weapons.[12] Over the next half year, new items were added and the government began co-funding marine insurance to compensate for the increased risk of loss due to naval warfare.

Bread prices were also subject to an early intervention. Agriculture weighed heavily in the economic composition of the country, yet there was not self-sufficiency in grain. Specialization in production based on livestock required more fodder than was available by local cultivation. With solid international demand for meat and milk products, diminishing supply from abroad would not stop farmers from feeding with grain. For the remainder of 1914 nothing much happened in that area but at the beginning of 1915, as inflationary pressure built up, the government introduced maximum prices on rye loaves, together with a mandatory minimum weight of each loaf passed over the counter. Rye bread formed the core of Danish lunch habits.

The measures mentioned so far became paradigmatic for the rest of the war period. With maximum prices came also the obligation to deliver to prevent suppliers from moving their goods to where competitive market forces still prevailed. On the other hand, maximum prices were set with a view to maintaining a normal level of sellers’ proceeds, taking due account of rising input prices. Transgressors were liable to a fine, and the authorities counted on members of the public to report irregularities. In less closely monitored lines of merchandise, some manufacturers sought advantage by splitting one intermediate transaction up into several, each time entailing phony added value in order to disguise supernormal profits.

With time, the basic economic conditions imposed by the war seriously reduced the amount of goods available for distribution. State subsidies, in cases where real costs ruled out low-price ceilings, encouraged overconsumption among those with ample purchasing power. With unrestricted German submarine warfare and the American turn in favour of the continental blockade in 1917, it proved necessary to introduce rationing in order to guarantee basic provisions, especially in protection of those of low means. The supply situation, however, was never so bad that ordinary consumers had insufficient quantities of victuals, soap, fuel and the like. Nevertheless, living costs were getting high. The situation of vulnerable households was somewhat relieved by the targeted handing out of benefits in kind or money transfer.

Labour Market↑

In the decade and a half before 1914, the Danish labour market had undergone a remarkable development. Employers’ organizations and labour unions made a grand compromise, at the core of which lay stable procedures to handle conflicts and a binding commitment to terms laid down in collective agreements. A special labour court enforced the system and workers’ unemployment funds began to receive sizeable subsidies.

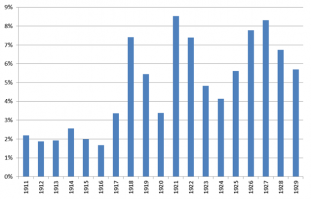

The period 1914-1918 became a testing ground for this collaborative arrangement. During the first half of the period, unions and their membership showed restraint in demands because of the fundamental uncertainties of the war. As one would expect, an erosion of real wages took place (see Table 1), even though business was quite good and unemployment figures remained low (see figure 2).

| Wage index (at full-time employment) | Work stoppages | |||

| Nominal Wages | Real wages | Number | Lost workdays | |

| 1913 | 100 | 100 | 76 | 381,500 |

| 1914 | 100 | 100 | 44 | 56,100 |

| 1915 | 102 | 88 | 43 | 31,900 |

| 1916 | 118 | 87 | 66 | 241,400 |

| 1917 | 133 | 86 | 215 | 214,400 |

| 1918 | 170 | 95 | 253 | 194,400 |

| 1919 | 268 | 125 | 472 | 915,900 |

| 1920 | 331 | 127 | 243 | 1,306,200 |

| 1921 | 319 | 138 | 110 | 1,321,200 |

Table 1: Wage and conflict levels on the Danish labour market, 1913-1921.[13]

Things began to change about halfway through the war. As employment opportunities became scarcer without halting inflation, workers’ real income came under increased pressure. Long-drawn-out negotiations resulted in an indexing system that granted the same rise to all male blue-collar workers regardless of previous hourly earnings.[14] After the war, this system was retained for some time and later reintroduced: indeed, it was officially acknowledged by means of a particular price index with focus on wage earners’ expenses.

The real test of collaborative labour relations came as the war approached its end and economic conditions worsened. Paradoxically, spirits tended to rise in popular circles. Left-wing factions within the labour movement began to mobilize based on opposition to the capitalist system that – as they perceived it – had given rise to the war. Against this backdrop, industrial action, anti-militarism and radical politics in general gained a footing among urban workers. In several unions, radicals either posed a threat to established leadership or did in fact take over. Overall, they were a minority, but the increased influence of their views set a new tone for industrial relations. A nervous mood was present among employers who chose to reaffirm their loyalty to the system of collaboration. For both sides much depended on preserving the corporatist wartime management of society.

Nevertheless, anti-establishment sentiments among the rank and file, from 1916-17 manifested by a significantly raised level of industrial conflict (Table 1), were strong enough to trigger important changes. As of 1 January 1920, the eight-hour day came into force in the urban industries. In addition, the wage boost of that period permanently increased wage-earners’ share of national income.[15] Thus, the immediate post-war situation was a window of opportunity for Labour to shift the socio-economic power balance.

International Trade and Trade Diplomacy↑

The Danish government’s policy of accommodation towards Germany was limited by the need to uphold trustworthy neutrality lest the Allies, and especially the British, refused to recognize Denmark’s neutral status. Before the war, Great Britain and Germany ranked, respectively, as number one and two in total Danish foreign trade volume (see Tables 2-3). Britain’s leading place in this respect resulted from its massive import of Danish butter and bacon. Conversely, German exports to Denmark normally outweighed its imports, although by a lesser margin.

| Note: Scandinavia = Sweden and Norway. | ||||||||||

| 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | |

| UK | 62% | 54% | 39% | 30% | 27% | 7% | 21% | 41% | 58% | 64% |

| Germany | 25% | 35% | 45% | 55% | 50% | 43% | 25% | 16% | 13% | 7% |

| Scandinavia | 4% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 15% | 39% | 32% | 22% | 11% | 10% |

| US | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 5% | 3% | 1% |

| Others | 8% | 6% | 11% | 9% | 8% | 10% | 18% | 15% | 15% | 18% |

| Quantity index, total | 100 | 114 | 102 | 90 | 72 | 33 | 43 | 83 | 88 | 97 |

Table 2: Distribution of Danish exports on recipient countries, 1913-1922.[16]

| Note: Scandinavia = Sweden and Norway. | ||||||||||

| 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | |

| UK | 16% | 18% | 22% | 25% | 26% | 21% | 31% | 27% | 18% | 22% |

| Germany | 38% | 33% | 17% | 20% | 22% | 33% | 13% | 16% | 27% | 31% |

| Scandinavia | 9% | 13% | 10% | 12% | 15% | 30% | 9% | 8% | 8% | 9% |

| US | 10% | 11% | 27% | 23% | 20% | 4% | 23% | 23% | 20% | 14% |

| Others | 26% | 25% | 23% | 21% | 16% | 12% | 24% | 25% | 26% | 24% |

| Quantity index, total | 100 | 88 | 100 | 86 | 46 | 33 | 89 | 88 | 89 | 109 |

Table 3: Distribution of Danish imports on countries of origin, 1913-1922.[17]

It was in Germany’s best interest to uphold trade with Denmark, above all as an importer of foodstuffs. German dependence on continental suppliers was among the reasons for war in the first place; after it broke out, the severing of all overseas trade links with Germany was an important element in British war plans. However, as long as neutral status was recognized there was no formal obstacle to selling Danish foodstuffs to Germany. The frictions of the wartime economy gradually limited volumes, but the land border between Denmark and Germany largely prevented the UK from stopping the trade by naval blockade. Nevertheless, the issue was sensitive. One cause of disagreement between Denmark and the UK was the possible abuse of goods exported bona fide from the UK, and re-exported to Germany.

Under these circumstances, the British had every reason to take advantage of Danish dependence on coal and other vital commodities. The UK preferred not to push the Danes into the arms of the enemy, but was in a position to impose requirements in order to minimize Denmark’s role as a supply base for Germany. This conflict of interests played out over several rounds of negotiations, each time aggravating Denmark’s situation until all British supplies – with the important exception of coal – had been stopped by October 1917.

In 1915, the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave up negotiating and managing deals governing the conduct of private firms abroad. Instead, representatives of business organizations, who included the chairman of the Federation of Danish Industries, the aforementioned Alexander Foss, took it upon themselves to establish the necessary agreements through talks with British diplomats. The British War Office demanded the opportunity to monitor the compliance of Danish firms with ever-tighter rules set up to prevent merchandise from the UK serving to free other resources for export to Germany.

Even with respect to agricultural produce, towards the end of the war, following the American involvement, the Allies put more pressure on the Danes to downsize the selling of domestic meat, butter, and livestock to Germany. Their officials argued that as long as their exports supported the Danish economy in any notable way, Danish trade with Germany constituted a breach of confidence and an affront to the Allied nations whose populations had to bear the brunt of the war.

It was in the German interest to prevent Danish compliance with Allied demands. Some pressure arose from the fact that Denmark also received vital products from Germany. The Danish side therefore counter-claimed with success that business in general would slow down without inputs from overseas, a prospect harmful to the Danish export ability vis-à-vis Germany. Nevertheless, reassurances had to be made, soothing for instance German preoccupation with growing activism of Allied agents in Copenhagen, meddling with the affairs of local industry and retrieving intelligence regarding German affairs.

The foreign secretary, Erik Scavenius (1877-1962), and other leading diplomats were well attuned to German discourse and lines of procedure. Even so, Danish trade policy in relation to Germany, 1914-18, did not reside exclusively within the inter-state framework, but included business organizations functioning as direct counterparts in bilateral agreements. Private negotiators acted independently, but not completely on their own as they consulted with the Foreign Ministry and sought approval on a continuous basis. The obvious motive for this setup was making sure that whichever agreements were made they did not conflict with the security of the state. The already strong involvement of leading business representatives in the wartime management of society facilitated this objective.

The prominent role of so-called business diplomacy is a question open to debate. The official apparatus may not have possessed sufficient resources to arrange, implement, and enforce complicated trade deals that were subject to frequent changes. It may also have been a matter of diplomatic convenience, as Germany perhaps felt intense trade dealings with the Allies less offensive when delegated to non-governmental agents. On the other hand, Sweden was, for better or worse, capable of mustering the resources for settling affairs under direct state auspices. From the outset, the Swedes were motivated by a greater eagerness to demand compliance with previously established rights of neutral nations, rules that the scale and scope of the current war successively undermined. However, when they finally yielded and began pragmatic accommodation by unprincipled deals, it still happened under tight political management.[18] By comparison then, the Danish solution did not necessarily reflect particular tactical and logistical ingenuity, but was simply one among two or more viable options.

Monetary and Financial Affairs↑

A short liquidity crisis accompanied the outbreak of war. A run on the banks was building up because many people preferred cash rather than deposits, and gold or silver rather than notes. Jointly, the central bank and government took the immediate precautions of rationing bank withdrawals and suspending convertibility to gold. Excess demand for silver was neutralized by issuing notes of smaller denomination than usual. Funds were made available for extraordinary state expenditure and rule-bound limits of cash supply expanded in order to guarantee a normal level of transactions.

A new semi-normal state of affairs followed the initial turbulence. In relation to other currencies, the krone, put in rough terms, remained on its pre-war parity value throughout the war, but then fell drastically;[19] the latter fact came to define the monetary policy of the 1920s. Regarding the balance of payments, figures are incomplete, but after the war, apparently, external debt as percentage of national income was smaller than before.[20] Beneath the tranquil surface, however, financial flows changed their pattern as did terms of trade and relative prices generally. Generous granting of credit supported sale of Danish products to the Central Powers.

The stock market leaned to the bullish side during the first years.[21] In Denmark, the already important shipping trade was highly profitable. Merchant vessels found rich opportunities as belligerent nations’ ships left the free commercial circuit. Customers accepted high freight rates in order to pay for the elevated risk level at sea and in anticipation of rising prices on end markets. The wartime profiteer became an icon of public resentment.

Meanwhile, problems were accumulating. In objective terms, the economy was in recession; nevertheless, a willingness to invest was present. This is unsurprising as inflation made it less attractive to hold liquid funds, yet banks were loaded with deposits. Possibilities for increased spending were limited as the supply of solid consumer goods was drying up. The building trade was slowing down due to lack of materials.[22] Investment in real capital still took place, but was hampered by the prevalent condition of short supply. Even some who were not by inclination opportunistic rent-seekers must have felt the urge to speculate.

Conclusion: Post-war Development↑

With the end of the war and the reopening of international trade in 1919, a short-lived boom set in. Stocks were replenished, reinvestment carried out, and peace and rising wages celebrated by consumers. This compensated for the downturn of the previous two years and reset turnover to a normal level. However, it did not imply a complete renormalization of the economy.

In Denmark, the payment of debt owed by foreigners contributed to financing the recovery. These means were soon exhausted, though. A massive public deficit, having been run in order to prop up the economy and secure adequate living standards, now had to be be phased out. Furthermore, there were problems on the supply side. Some highly capitalized firms were unsuccessful in reorienting their activities towards peacetime conditions with falling prices and changing demand structure.

Unfortunately, not only private investors lost their stakes. Banks incurred irreparable losses as risky loans turned sour. In 1922, the largest bank in Denmark was reconstructed following bankruptcy. Similar or worse fates befell many minor banks during the 1920s. The immediate cause of this was professional neglect on the part of bankers, but behind it all lay also the pressure during the war years to recirculate abundant deposits generated by the discrepancy between realized earnings and, in the next phase of the monetary cycle, more and more limited natural outlets for investment and purchasing power. The lack of firm financial regulation was also to blame.[23]

These events contributed to a lack of stability in the post-war period. Real wages rose on an irregular basis. Unemployment figures too fluctuated a great deal, without any permanent decrease compared to the final war years. Overall, the economic situation was less than satisfactory. Policy-makers were much in doubt regarding what to do even though options were limited within the narrow, pre-Keynesian horizon of those years.

The big question was the exchange rate. Fearing inflation, the ideal was a return to the pre-war par value of the krone. By 1923, the government and the central bank decided to pursue a tight monetary policy. A high interest level would attract foreign exchange and facilitate an expansion of the national gold stock. Indeed, in 1926 the krone reacquired its pre-war value. The dark side of such reassurance was a relatively high level of unemployment. Decision-makers, convinced that the economy was back on a sound footing, were unable to envisage the international breakdown of the gold standard half a decade later.

In the meantime, the pendulum had swung away from regulation and redistribution but did not again reach the opposite extreme. The public sector’s size measured against national income diminished after the peak year 1918 but remained several percentage points above the pre-war level throughout the liberalizing 1920s and continued its rise after that.[24] Later regulation and redistribution, during the Great Depression as well as the Second World War, drew on the experience of the war years, but with direct business interests in a less prominent role. The corporatist approach remained a permanent feature.

The origin of this new socio-political setup in the First World War was not random events that triggered a path-dependent chain of other, analogous events. Change was due even if the Great War had failed to materialize. It was contingent on broader, structural transformation in the spheres of political economy and mass politics. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that 1914-18 was a transformative period in Denmark, shaping the agenda for future social and civil governance.

Jan Pedersen, University of Copenhagen

Section Editor: Nils Arne Sørensen

Notes

- ↑ Cohn, Einar: Danmark under den store Krig. En økonomisk Oversigt [Denmark during the Great War. An Economic Survey], Copenhagen 1928.

- ↑ Cohn, Einar: Denmark in the Great War, in: Shotwell, James T. (ed.): Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland in the World War, New Haven 1930, pp. 409-558.

- ↑ Dalhoff, Johannes: Krigsaarenes Lønpolitik. Foredrag i Nationaløkonomisk Forening den 30. November 1920 [The Pay Policy of the War Years. Lecture at the Danish Economists’ Association 30 November 1920], in: Nationaløkonomisk Tidsskrift 29/4 (1921), pp. 1-36.

- ↑ Hansen, Svend Aage: Økonomisk vækst i Danmark [Economic Growth in Denmark], volume 2, Copenhagen 1974.

- ↑ Hansen, Svend Aage / Henriksen, Ingrid: Dansk socialhistorie 1914-39. Sociale brydninger [Danish Social History 1914-39. A Time of Social Unrest], Copenhagen 1980.

- ↑ Olsen, Erling: Perioden 1914-1931 [The Period 1914-1931], in: Olsen, Erling / Hoffmeyer, Erik (eds.): Dansk pengehistorie 1914-1960 [Danish Monetary History, 1914-1960], Danmarks Nationalbank 1968, pp. 11-152.

- ↑ Jørgensen, Kasper Elmquist: Studier i samspillet mellem stat og erhvervsliv i Danmark under 1. Verdenskrig [Studies in the Interplay between Government and Business during the First World War], Copenhagen Business School 2005.

- ↑ Andersen, Steen / Jacobsen, Kurt: Foss [Foss], Copenhagen 2008; Andersen, Steen / Jacobsen, Kurt: Fra åben til reguleret økonomi. Foss, Rode og Den Overordentlige Kommission [From Open Economy to Regulation. Foss, Rode and the Special Commission], Økonomi og Politik 82/3 (2009), pp. 15-28.

- ↑ Due-Nielsen, Carsten: Denmark and the First World War, in: Scandinavian Journal of History 10/1 (1985), pp. 1-18.

- ↑ Den overordentlige kommission af 8. august 1914. Virksomheden fra 8. august til 7. november 1914. Beretning – aktstykker [The Special Permanent Commission of 8 August 1914. Activities from 8 August 1914 to 7 November 1914. Report and Documents], p. 15, online: http://www.kb.dk/e-mat/ww1/130018363977.pdf (retrieved: 15 February 2017).

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 19.

- ↑ Cohn, Danmark under den store Krig 1928, p. 284 (wage index); Mikkelsen, Flemming: Arbejdskonflikter i Skandinavien 1848-1980 [Industrial Dispute in Scandinavia, 1848-1980], Odense 1982, Table A7 (work stoppages).

- ↑ Kocik, A. / Grünbaum, Henry: Organisationens historie [The History of the Organization], in: Under Samvirkets Flag. DSF 1898-1948 [Under the Banner of the Confederation, 1898-1948], Danish Confederation of Trade Unions 1948, pp. 115-117, 127.

- ↑ Kærgård, Niels: Økonomisk vækst. En økonometrisk analyse af Danmark 1870-1981 [Economic Growth. An Econometric Analysis of Denmark, 1870-1981], Copenhagen 1991, p. 143, especially Figure 6.7.

- ↑ Johansen, Hans Chr.: Dansk økonomisk statistik 1814-1980 (Danish historical statistics 1814-1980), Copenhagen 1985, Table 4.5a (distribution); Cohn, Danmark under den store Krig 1928, p. 312 (quantity index).

- ↑ Johansen, Hans Chr.: Dansk økonomisk statistik 1814-1980 (Danish historical statistics 1814-1980), Copenhagen 1985, Table 4.5b (distribution); Cohn, Danmark under den store Krig 1928, p. 312 (quantity index).

- ↑ Bergendahl, Kurt: Trade and Shipping Policy in the War, in: Shotwell, James T. (ed.): Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland in the World War, New Haven 1930, pp. 120-24.

- ↑ Johansen, Hans Chr.: Dansk økonomisk statistik 1814-1980 [Danish historical statistics 1814-1980] [Note: bilingual title; table headings are rendered in English as well as Danish], Copenhagen 1985, Tables 6.4 and 6.5.

- ↑ Based on ibid., Tables 4.8 and 10.1, 1907, 1912, 1923 and subsequent years.

- ↑ Cohn, Danmark under den store Krig 1928, pp. 314-315.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 85, 189-91.

- ↑ Full story in Hansen, Per H.: På glidebanen til den bitre ende. Dansk bankvæsen I krise, 1920-1933 [Sliding towards the Bitter End. The Crisis of Danish Banking, 1920-1933], Odense 1996.

- ↑ Norstrand, Rolf: De offentlige udgifters vækst i Danmark [The Growth of Public Expenditure in Denmark], University of Copenhagen, Department of Economics (Blue Memo No. 41), 1975.

Selected Bibliography

- Andersen, Steen / Jacobsen, Kurt: Foss, Copenhagen 2008: Børsens Forlag.

- Andersen, Steen / Jacobsen, Kurt: Fra åben til reguleret økonomi. Foss, Rode og Den Overordentlige Kommission (From open economy to regulation. Foss, Rode and the special commission), in: Økonomi og Politik 82/3, 2009, pp. 15-28

- Cohn, Einar David: Danmark under den store krig. En økonomisk oversigt (Denmark during the Great War. An economic overview), Copenhagen 1928: G. E. C. Gad.

- Cohn, Einar David: Denmark in the Great War, in: Shotwell, James T. (ed.): Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland in the World War, New Haven 1930, pp. 409-558.

- Dalhoff, Johannes: Krigsaarenes lønpolitik. Foredrag i Nationaløkonomisk Forening den 30. November 1920 (The pay policy of the war years. Lecture in the Danish Economists’ Association 30 November 1920), in: Nationaløkonomisk Tidsskrift 29/4, pp. 1-36.

- Due‐Nielsen, Carsten: Denmark and the First World War, in: Scandinavian Journal of History 10/1, 1985, pp. 1-18.

- Hansen, Per Henning: På glidebanen til den bitre ende. Dansk bankvæsen i krise, 1920-1933 (Sliding towards the bitter end. The crisis of Danish banking, 1920-1933), Odense 1996: Odense Universitetsforlag.

- Hansen, Svend Aage: Økonomisk vækst i Danmark (Economic growth in Denmark), volume 2, Copenhagen 1974: Akademisk Forlag.

- Hansen, Svend Aage / Henriksen, Ingrid: Sociale brydninger. Dansk social historie 1914-1939 (Social conflicts. Danish social history 1914-1939), Copenhagen 1984: Gyldendal.

- Jørgensen, Kasper Elmquist: Studier i samspillet mellem stat og erhvervsliv i Danmark under 1. verdenskrig (Studies in the interaction between government and business interests in Denmark during World War I), Copenhagen 2005: Copenhagen Business School.

- Olsen, Erling: Perioden 1914-1931 (The period 1914-1931), in: Olsen, Erling / Hoffmeyer, Eric (eds.): Dansk pengehistorie 1914-1960 (Danish monetary history, 1914-1960), Copenhagen 1968: Danmarks Nationalbank, pp. 11-152.