Introduction↑

In 1864, Prussia and Austria defeated Denmark and conquered the Danish duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenborg. In 1867, Schleswig and Holstein became part of Prussia, and in 1871, the duchies were absorbed into the German Empire. However, the majority of the population in the northern half of Schleswig, with the market towns of Haderslev, Aabenraa, Sønderborg and Tønder, remained Danish-speaking and retained their adherence to Denmark. With their own Danish press, sweeping political, economic and cultural organisations, and with widespread support from Denmark, this Danish-minded part of the population managed to stand their ground, despite growing Germanisation and state support for those with German sympathies. In the years immediately following 1864, most young men emigrated to avoid military service for Prussia, but from the 1880s it became the norm for young men from the minority to serve in the Prussian army in order to retain their Prussian citizenship. Loyalty to the Prussian state went hand in hand with an assertion of their Danishness and the hope of reunion with Denmark. As a minor state, the minority’s Danish mother country was forced to lead a strict policy of neutrality, but with leanings towards Germany. Therefore, most of the support for the Danish North Schleswigians came from private organisations in Denmark and was limited to financial and cultural support.

Danish North Schleswigians during the First World War↑

Reactions at the Outbreak of War↑

When, on 1 August 1914, church bells and red posters heralded German mobilisation of all men between twenty and forty-five, the reaction in rural North Schleswig was grim. There was sporadic enthusiasm for the war from high-school students and student teachers with German leanings, but this soon evaporated. H.P. Hanssen (1862-1936) represented the Danish North Schleswigians in the German Reichstag in Berlin, and observed very different emotions in these people at the call to arms: “I shall never forget the picture: Pale, serious men, dully resigned; women in tears; young couples clinging to each other oblivious to their surroundings; sobbing children. Everyone felt they were in the harsh, uncompromising and inexorable embrace of fate.”[1] Following the tradition of the minority to “do your duty and demand your rights”, all the Danish-minded soldiers reported to their units.

Discrimination during the War↑

Rumours abounded when the entire German press was suddenly subject to censorship. Danish minority newspapers were completely banned. They were not permitted to publish again until the end of August and early in September, but then only under strict censorship and with orders to publish official telegrams. Immediately after the outbreak of war, the leaders of the Danish movement were interned. A total of 172 people from North Schleswig, and two from South Schleswig, were arrested as “political suspects”. Moreover, 118 pilot-boat crew and fishermen were also interned because the military feared they would go to the aid of an enemy fleet. H.P. Hanssen was arrested on 31 July, but released the following day because of his parliamentary immunity as a member of the Reichstag. Other civilian prisoners were released at the end of August or in early September, although one was held until early December. In order to be released, civilian prisoners had to pledge in writing that they would not take part in Danish organisations or Danish meetings. This order had no practical significance, as Danish organisations and meetings were more or less dormant during the war.

Many soldiers from North Schleswig served in “Danish regiments”: The 84th Infantry Regiment, 86th Fusiliers and the 86th Reserve Infantry Regiment were garrisoned at several camps in Schleswig. As the war progressed, however, North Schleswigian soldiers were increasingly disbursed to other units. They were insignificant in the enormous German army and served on an equal footing with their German comrades. Sometimes, the Danish-speaking soldiers were discriminated against. In some military units, they were forbidden from using their language in the company of fellow North Schleswigian comrades and in the letters they sent home. Some authorities marked the names of conscripts with Danish sympathies on lists of personnel as “Dane – to be called up if possible”. Later in the war, Danish-minded soldiers found it increasingly difficult to get leave because of fears that they would desert.

North Schleswigian Experiences of War↑

Close to 35,000 men from North Schleswig were called up during the war, of whom up to 75 percent probably had sympathies for Denmark. At the front, they shared the same experiences as other soldiers in the German army and soldiers from the other warring nations. With a life of terrifying action and tedious waiting, of death and mutilation, disease and hunger, and with constant longing for their loved ones, the soldiers’ mutual sense of comradeship and their ties with their homes and families via letters and packages were all they had to raise their spirits. Comradeship in arms was the key to survival, and this could be with other soldiers with sympathies for Denmark, German-minded North Schleswigians, or Germans from other parts of the German Empire. When possible, soldiers from North Schleswig sought out each other’s company. The feeling of meaninglessness that gripped a large number of those involved in the war took on an extra dimension for the Danish-minded soldiers who were forced to fight for the country that suppressed their culture. They shared their fate with other national minorities. Poles and Frenchmen in the German, Austro-Hungarian or Russian armies also risked having to fight against their own compatriots. Danes from northern Schleswig were at least spared this, as Denmark remained neutral throughout the war.

Desertions↑

Danish neutrality also made it possible for soldiers at home on leave and those not yet called up to flee northwards across the border to Denmark and escape the war. Desertions began after the Danish-minded soldiers had first experienced the horrors of war, even though the leaders of the minority disassociated themselves from these desertions. They first crept across the border in the winter of 1914-15. Almost 2,500 took advantage of the opportunity, the majority from northernmost areas. Many were helped across by guides. In Denmark, they could expect a warm welcome from family, friends and acquaintances, and the “Two Lions” conservative student union organised an aid service.

Deserters risked losing their Prussian citizenship and having their assets confiscated. Furthermore, if their escape went awry, a harsh prison term awaited before they were returned to the front. North Schleswigian soldiers were banned from taking leave north of a line from Flensburg-Dagebüll in order to prevent desertion. The ban was introduced in 1916, but it was not rigidly enforced.

Danish Soldiers captured by the Allies↑

The war could also come to an end for soldiers who were captured. This was the fate of up to 4,000 Danish North Schleswigian soldiers. In time they were gathered in three special camps where they were treated favourably because of their non-German backgrounds. These camps were established due to private initiatives. In the spring of 1915 a camp was established for Danish North Schleswigians in Aurillac in southern France. In the spring of 1916 the same was the case in Feltham, close to London. This camp also housed Poles and prisoners from Alsace. In Russia, some Danish North Schleswigian prisoners were transported to a special camp just before Christmas 1915 in Pavlovo Posadsky, and from autumn 1917 in Yuryev Polsky. The latter two camps east of Moscow also held prisoners of other, non-German nationalities. After the Russian Revolution and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the prisoners from Russia returned home in small groups in 1917-18. At the initiative of the Danish government, the North Schleswigian prisoners of war from the Western Front were brought home in Danish ships between March and July 1919.

The Home Front in North Schleswig↑

Acts of War and Defence Works↑

Only one action took place in North Schleswig during the war. This was when British aircraft from the carrier HMS Furious bombed the major Zeppelin base just north of Tønder on 19 July 1918. Two airships were set alight, but no one was killed. However, the German general staff feared a British invasion from the north. In 1916-17, a defence work called Sicherungsstellung Nord was constructed across North Schleswig, with two lines of trenches, barbed wire barriers, sluices for flooding moats, bunkers, railways and artillery positions to guard against a possible British landing at Esbjerg. However, such an attack against the German northern flank never took place and the position was never used. Parts of the defences remain preserved to this day.

Living Conditions on the Home Front↑

Living conditions deteriorated for women, children and the elderly on the “home front”. Even in a predominantly rural region like North Schleswig, food shortages took hold from early on in the war. Agriculture lacked labour, animal feed and fertilizer. Milk and crop yields fell drastically. In order to keep price increases in check, maximum prices were soon imposed on staples such as bread and potatoes. In January 1915, compulsory surrender of bread grain was introduced and bread was rationed from March in the same year. From autumn 1916, people had to mix barley in bread dough. As time passed, all agricultural produce was subject to compulsory surrender and rationing. Despite this, the winter 1916/17 brought shortages when the potato harvest failed. People had to eat swede instead.

In the countryside, police patrolled to prevent illegal butchering, butter churning or bread baking, but they could not prevent it and could, perhaps, be bribed to turn a blind eye. People living in towns had no such option. Town councils and private groups intervened to buy up food, set up public kitchens, distribute skimmed milk from dairies, and so on. This helped, but it was not enough. The same applied for “Ersatz”, the large number of substitute products that emerged. In the final year of the war, rations were as low as 1,000 calories a day: one third of the normal requirement for a labourer. Undernourishment and the diseases that follow became widespread. Protests resulted in the winter of 1917/18. In Haderslev, a town of 13,000 inhabitants, as many as 400 women demonstrated for more milk, flour, barley and other produce which was otherwise transported to the south to help people living in large towns and cities.

The war put a lot of pressure on women in general. They were alone in feeding and clothing their household. They were alone in looking after their children, and this became apparent in the way children were brought up. Furthermore, they had to do the men’s work on the fields and in stables, workshops, factories, offices and shops. War propaganda bombarded eyes and ears on the home front. The First World War was the first total war. Time and again there were appeals for people to make sacrifices, to offer war loans and to deliver any metal they may have had. Schoolchildren made collections and were sent out to work in the fields, while the Red Cross and Vaterländische Frauenverein sent “Liebesgaben” or food packages to soldiers.

Allied Prisoners of War in North Schleswig↑

About 7,000 of the allied soldiers captured by the Germans were set to work in North Schleswig. About 75 percent of them were Russians. Prisoners were sent from large camps near Løgumkloster and Tinglev to work on the fields, but many fell victim to cold, hunger and disease. Thousands of others were sent to villages in small groups guarded by older soldiers to help on farms. The hard-working Russian prisoners who were used to farm work were especially useful and sometimes, in return, they were treated more favourably than the authorities wanted.

The End of the War and its Consequences↑

The German Revolution and the End of the War↑

The German Revolution of November 1918 spread like wildfire from Kiel to North Schleswig and elsewhere. Soldier councils (Soldatenräte) were established in the garrison towns: in Flensburg on 5 November, in Tønder on 5/6 November, in Sønderborg and Aabenraa on 6 November and in Haderslev on 7 November. Soldiers marked the revolution by raising the red flag at the garrisons. In its first three days, the soldier council in Sønderborg appointed Bruno Topff (1886-1920), a marine from Potsdam, as its chairman, or president as the position was called in the union movement. He declared the republic in the marines’ field hospital. These two incidents have since encouraged the local myth that he declared the island of Als as an independent republic with himself as its president.

Local labour councils were also set up, and these focussed on managing the distribution of food. The labour and soldier councils soon joined forces. At least four soldier councils were formed in smaller towns in North Schleswig, as well as at least three labour councils and six joint soldier and labour councils. Farmworkers’ councils were established in rural areas, but they had little importance.

In Berlin, the revolution led to Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) being deposed on 9 November and a German republic was declared. Germany signed the Allies’ conditions for a ceasefire on the following day. The Great War ended on 11 November. The soldiers from North Schleswig could finally go home. The end of the war brought with it mixed feelings for German-minded North Schleswigians as they grieved over the defeat of the Empire, but for the Danes there was hope of unification with Denmark.

War Losses↑

The First World War was extremely costly for North Schleswigians across the national divide. On the home front it led to serious deterioration of infrastructure and industry, which took a decade of hard toil to rebuild. But it was worst for the soldiers. About 4,000 returned home invalids. Some were treated and retrained to take up their old jobs again. Others were trained for new jobs. From 1920 to 1925 this was at Krigsinvalideskolen (a school for veterans) in Sønderborg. From 1920 to 1990 there was also the Invalidenævnet for de sønderjyske Landsdele (Council for the Disabled for the Southern Jutland region), which determined amounts for long-term support to compensate soldiers for loss of ability to work. After 1990, the Municipality of Sønderborg took over this responsibility. The last disabled veteran died in 1996. The council for the disabled was also responsible for helping the surviving relatives of the fallen: about 1,100 widows, 3,100 fatherless children and 400 others, primarily elderly parents. Also in this context, the shadows of war also reached far into the future, with the last widow dying in 2007.

The greatest loss was the number of fallen. A total of 6,100 soldiers from North Schleswig lost their lives, of whom about 5,300 were born and bred in the region and of whom almost 4,000 probably had Danish sympathies. Many family tragedies lie behind these figures. Among the hardest hit were Jens Peter Jensen (1854-1918) and Marine Jensen (1868-1942) from Hviding, who lost four sons, while three other sons, returned home as invalids. One of the sons who made it home died a few years later of a lung disorder caused by a gas attack during the war. An eighth brother was injured on the arm.

Addressing a Danish meeting in Aabenraa on 17 November 1918, H.P. Hanssen tried to give some meaning to the loss suffered by surviving relatives: that their loss was the price for the reunification of North Schleswig with Denmark, see Solution of the border issue 1918-1920, below.

Veterans’ Organisations and the Heritage Culture↑

In 1922, German North Schleswigians set up their veterans’ association, Verband der Vereine ehemaliger deutscher Soldaten im abgetretenen Nordschleswig. The Danes established their association in 1936 – Foreningen af Dansksindede Sønderjydske Krigsdeltagere 1914-18, abbreviated to D.S.K. At its peak in the 1940s the association brought together almost 8,000 members. Numbers fell after this until the final remaining thirty-seven comrades in arms decided in 1988 to close down D.S.K. The last member died in 2004.

D.S.K. introduced the custom of laying a wreath on Armistice Day, 11 November. This was in cemeteries near the many memorials to the fallen raised in the early 1920s. The custom is still kept by local church councils. D.S.K. also attended with the Danish flag at funerals of deceased comrades and they held dinners with servings of split peas and pork for comrades and their wives. In 1934, a major monument for the fallen of North Schleswig was inaugurated at a memorial park at Marselisborg castle in the main Jutland city of Aarhus, engraved with all their names. In contrast to the local memorials, that almost always include Danish and German North Schleswigians, the Marselisborg monument includes only the Danes.

The Schleswig Border Issue and its Solution↑

The Border Issue during the War↑

Despite German advances at the start of the war, hope that the border would be moved lived on in the Danish-minded population. On 11 September 1914, the politician H.P. Hanssen wrote in his diary:

Rumours circulated in autumn 1915 that North Schleswig would be returned to Denmark. Although the president of the Province of Schleswig-Holstein officially denied the truth of the rumours, rather than putting things to rest, this raised more debate on the border issue. Because of its neutrality policy, the Danish government wanted to mute the border issue, and it successfully influenced the Danish press to let the issue lie.

In summer 1917, representatives from several European socialist parties gathered for a peace conference in Stockholm. The closing document from the conference stated that, when peace arrived, the North Schleswig issue should be resolved by moving the border in accordance with a referendum and an amicable agreement between the countries involved. The resolution gave rise to renewed rumours, and in December 1917 the president issued a new denial. In January 1918, US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) made public his famous “14 Points” for the coming peace. The right to self-determination was a central element in this document, but North Schleswig was not mentioned as an area where self-determination might apply.

Solution of the Border Issue 1918-1920↑

At the end of September 1918, H.P. Hanssen knew that the German collapse was imminent. On 23 October, he demanded reunification of North Schleswig with Denmark in the German Reichstag. On the same day, the Danish parliament adopted a resolution to have the border issue resolved in accordance with the principle of nationality.

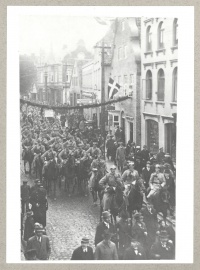

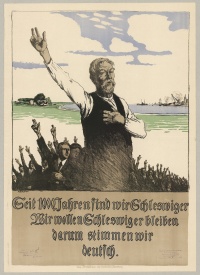

The Danish North Schleswigians’ own border policy was finally formulated after the ceasefire at a meeting of the Danish Electors Association at the “Folkehjem” in Aabenraa on 16/17 November 1918. A resolution was adopted at the meeting demanding that the border be drawn following a referendum. North Schleswig was to vote as one, but the adjacent districts in South Schleswig, including the principal town of Flensburg, could vote by municipality, if they so demanded. At the close of the meeting, from the balcony of the Folkehjem, H.P. Hanssen could announce the decision of the Electors Association to the assembled crowd of 3,000 people, assuring them that the likelihood of reunification with Denmark was very strong indeed.

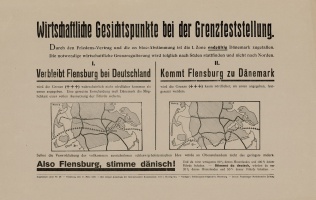

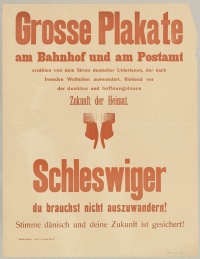

The Aabenraa resolution was sent to the Danish government, who then forwarded it to the allies to have the issue addressed at the coming peace conference. The Aabenraa resolution formed the basis of the Schleswig provisions in the Treaty of Versailles. Articles 109 to 114 of the treaty provided for international occupation and administration of the area and for the allies overseeing the referendum. The referendum area was divided into two zones: the first zone corresponded to the proposal by the Electors Association; the second zone covered Flensburg and the northern part of South Schleswig.

On 10 January 1920, an international commission took over administration of the two referendum zones. On 10 February, 102,000 people cast their vote in the first zone: a voting turnout of 91 percent. A total of 75 percent of the votes were in favour of the reunification of North Schleswig with Denmark, while 25 percent preferred to remain with Germany. On 14 March, 65,000 people voted in the second zone. The turnout was just as high. Here, 80 percent voted for mid-Schleswig to remain German and 20 percent voted for reunification with Denmark. The result was clear, and in the summer of 1920, the border was set in accordance with the results of the referenda. The German-minded people in North Schleswig and the Danish in South Schleswig then organised themselves into national minorities, who even today continue to put their mark on the border area.

Conclusion↑

The Danish minority in Schleswig carried the same burden as the rest of the population of the German Empire in 1914-1918. Furthermore, soldiers from the minority had to fight for the country that had repressed their culture, and sometimes they had to suffer a certain amount of discrimination. The defeat of Germany formed the foundation for reunification with Denmark in accordance with a fair, democratic referendum, and it provided a peaceful and lasting solution to the Danish-German border conflict.

Hans Schultz Hansen, Danish National Archives

Section Editor: Nils Arne Sørensen

Translator:

Notes

- ↑ Hanssen, H.P.: Fra Krigstiden. Dagbogsoptegnelser 1 [From the War Years. Diary Notes], Copenhagen 1924, p. 9.

- ↑ M. Andresen was the president of the association to protect the Danish language in North Schleswig. Hanssen, H.P.: Fra Krigstiden. Dagbogsoptegnelser 1 [From the War Years. Diary Notes], Copenhagen 1924, p. 63.

Selected Bibliography

- Adriansen, Inge: Ivan fra Odessa. Krigsfanger i Nordslesvig og Danmark 1914-1920 (Ivan from Odessa. Prisoners of war in North Schleswig and Denmark 1914-1920), Sønderborg 1991: Historisk Samfund for Als og Sundeved.

- Adriansen, Inge / Hansen, Hans Schultz (eds.): Sønderjyderne og den Store Krig 1914-1918 (The North Schleswigers and the Great War 1914-1918), Aabenraa 2006: Museum Sønderjylland; Historisk Samfund for Sønderjylland.

- Christensen, Claus Bundgård: Danskere på Vestfronten, 1914-1918 (Danes on the Western Front, 1914-1918), Copenhagen 2009: Gyldendal.

- Falkner Sørensen, Svend: Faneflugt? Dansksindede soldaters flugt fra tysk krigstjeneste 1914-18 (Desertation? The Escape of Danish minded soldiers from German service 1914-18), Aabenraa 1989: Historisk Samfund for Sønderjylland.

- Hansen, Hans Schultz / Becker-Christensen, Henrik: Sønderjyllands historie. Efter 1815 (History of Schleswig. After 1815), volume 2, Aabenraa 2009: Historisk Samfund for Sønderjylland.

- Hanssen, Hans Peter: Fra krigstiden. Dagbogsoptegnelser (From the war years. Diary notes), 2 volumes, Copenhagen 1924: Gyldendal.

- Hanssen, Hans Peter: Grænsespørgsmaalet. Bidrag till dets historie (The border question. Contributions to its history), Copenhagen 1920: Gyldendal.

- Øjenvidner 1914-1918. Sønderjyske soldaters beretninger (Eyewitnesses 1914-1914. Narratives from North Schleswigian soldiers), Copenhagen 2014: Lindhardt og Ringhof

- Marckmann, Anton: Ofrene fra den store krig, 1914-1918 (The victims of the Great War, 1914-1918), Aabenraa 2005: Historisk Samfund for Sønderjylland.

- Thorsen, Svend / Thomsen, Ingeborg (eds.): De fire onde Aar. Dagligt liv i Sønderjylland under Verdenskrigen (The four evil years. Daily life in Southern Jutland during the World War), Copenhagen 1933: Gad.