Introduction↑

The traditional narrative of Danish neutrality during the First World War underlines how well the government of the Social Liberal Party (Det Radikale Venstre) balanced the country throughout the war. It succeeded in maintaining trade with both sides, adjusting social policies to reduce injustice when economic hardship followed resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in the winter of 1917. According to this narrative, the country kept a military profile that minimised provoking Germany, the only real threat to Denmark. The policy had to compensate for the inherently negative view most Danes had of a country that was oppressing their compatriots in North Schleswig.[1]

Based on new research into the archives of both the Danish armed forces and foreign service, this article will update the traditional narrative in relation to the responses to perceived and real German wishes and pressures. Kristian Bruhn’s in-depth analysis of Danish intelligence efforts before and during the war years continues this new research. The organisation of the article is chronological, allowing the reader to follow how key persons learned and adjusted to what they saw as necessary – not only in relation to keeping Denmark out of the conflict, but also to consolidating their own political power and promoting the ruling party’s ideal of a disarmed country incapable of military folly. It will be clear that the continuous, pro-active actions would end up leaving the country in a situation in spring 1918 very similar to that of two decades later.

The Armed Forces of the 1909 Defence Laws↑

After mobilisation, the Danish armed forces consisted of the Copenhagen land and coastal fortress, four obsolete coastal armoured vessels, a couple of small old cruisers, twelve small torpedo boats and, later, twelve coastal submarines. The field army would reach the strength of three very light infantry divisions. However, given that the peace-time army was purely a training organisation, it took many weeks before the field army would become combat effective.[2]

The Conflicting Notions of Danish Neutrality Strategy↑

To understand Denmark’s survival strategy during the war, it is essential to accept the fundamental division inside the civilian-military leadership in two areas: The first disagreement was about the armed forces’ role. The Social Liberal government, in power from summer 1913, simply rejected that a small neutral state such as Denmark had an obligation to defend its neutrality against a violation by a great power, as it implied a duty to accept the resulting deaths and destruction.

The government was led by the lawyer Carl Theodor Zahle (1866-1946) as prime minister and justice minister, with the diplomat Erik Scavenius (1877-1962) as foreign affairs minister and the historian Dr Peter Munch (1870-1948) as defence minister. In Munch and Zahle’s opinion, Denmark was only obliged to register the aggression as a breach of international law. Marking neutrality was a legal issue and thus a task for the police rather than the armed forces. At the sea border, the navy had to assist the police. The party rejected the notion that Danish armed forces could influence great powers’ decisions by creating a deterrent threshold. Armed forces could only provoke enmity and thus trigger aggression, and fortresses would attract great power use.[3] Keeping the armed forces too small for defensive operations would limit the risk of some commanding general triggering war.

The first mission of the armed forces was to deter a coup attack against Copenhagen. After mobilisation, they were to defend the main island, Zealand, and guard the adjoining territorial waters on both sides of the Great Belt against one belligerent’s use of Danish territory against the opponent, mainly English use against Germany. The incoming government had committed itself to administering the Defence Laws loyally. Yet, it never committed itself to mobilising and employing the armed forces in a potentially suicidal neutrality defence strategy if Denmark was invaded. However, Munch’s intent to disarm in order to avoid destruction was only documented by his actions. The minority government had to be discreet about its intention for that – hopefully avoidable – hypothetical situation.

The second disagreement was about the degree to which it was acceptable to tip the neutrality defence posture in favour of Germany to lessen any concerns about a possible attack via Denmark and the Great Belt against Northern Germany and the Baltic Sea. The navy commander, Vice-Admiral Otto Kofoed-Hansen (1854-1918), favoured taking maximum care of German interests to the extent possible within the bounds of his view of national honour. This “German course” (Tyskerkurs) was eagerly supported by the foreign minister and his key assistants, such as his permanent undersecretary, Herluf Zahle (1873-1941), and the Danish minister in Berlin, Count Carl Moltke (1869-1935). The government knew that the political father of the Defence Laws, the Liberal Party and Opposition leader Jens Christian Christensen (1856-1930), concurred. Christian X, King of Denmark (1870-1947), the army leadership, the Conservative Party and the right wing of the Liberal Party considered such a line as both morally and politically unacceptable, as Germany’s enemies were Denmark’s natural allies.

The Start of the War to Summer 1915↑

The government had reacted to the slide towards European war by calling up the small neutrality guard prepared in line with the Defence Act and had successfully resisted the pressure to mobilise. It received information in the early morning of 5 August 1914 that the German navy was mining the southern end of the Great Belt, followed by a note with the German request for Denmark to mine the Great Belt against both sides. The note was a German reaction to the coming war with the British Empire, and it was read by the Danish decision-makers as an ultimatum. The government relinquished control of the reply, and the vice-admiral led the king to believe that the mine fields could be controlled and thus disarmed from the moment they were laid. The monarch communicated to his British cousin that the barriers would be opened if his navy tried to enter the Baltic Sea. Christian X’s support led to a positive reply to the German note. The government’s needs for political support meant that the existing humble army neutrality guard was enlarged to roughly two-thirds of the army’s fully mobilised strength.

The vice-admiral dispatched nearly half his operational surface fleet as an independent squadron to the Great Belt to create and defend the barrier, as well as smaller mine fields meant to protect a southern transit route to the Sound. The squadron was thereafter directed to fight in support of the barrier in the case of a British operation to break through to the Baltic Sea. This order to fight a belligerent great power was in conflict with both the government’s security concept and with the logic behind the defence structure that force should only be used against open belligerent use of Danish territory. However, the admiral got the support of the foreign minister, Erik Scavenius, as the Germans would applaud this robust line. To Scavenius, Danish use of force was meaningful when used against Germany’s enemies. Even before the admiral succeeded in getting his Great Belt Squadron Directive approved in October 1914, he had changed the focus of the growing submarine flotilla from defence against German landings in Koege Bight to countering a British bombardment squadron approaching Copenhagen from the north.

In spring 1915, the government countered German criticism of Entente intelligence activities in Denmark by allowing Germany to establish a counter-intelligence office in Copenhagen, something not offered to her enemies. During the same period, Count Moltke and Scavenius agreed to use the Danish Berlin legation as the basis for financing pro-German propaganda in Denmark.[4] During the summer of 1915, the government succeeded in achieving a significant reduction of the large army neutrality guard force. The 5 August 1914 call-up had created a force strong enough to defend without a mobilisation that the government might veto. The summer reductions undermined that possibility.

Autumn 1915 to Spring 1916: British Submarines and the Reactions↑

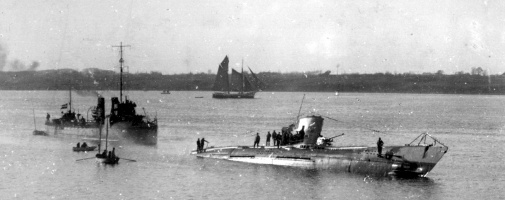

On 19 August 1915, when a German torpedo boat attacked and destroyed the British submarine E13 stranded in Danish territorial waters, the Danish navy failed totally in its duty to defend the submarine and half its crew died. However, if this serious German violation of Danish neutrality had been resisted by force, which the admiral considered essential for national honour, the exchange of fire might have undermined the neutrality strategy sought by both the admiral and his foreign minister.

In their perspective, it was therefore essential to remove the risk of similar incidents in the future. That could only be done by blocking all access routes to the Baltic Sea to British submarines. The Great and Little Belts were already closed by both German and Danish obstacles, but as an international strait between Denmark and Sweden, the Flint Channel used by the British boats was diplomatically far more difficult to block.

However, the clear success of the British Baltic submarine flotilla against both the German navy and merchant shipping along the Swedish east coast soon removed the political and legal obstacles. During the months from September 1915 to June 1916, the Sound was closed effectively to additional British submarines by the tacitly co-ordinated German-Danish-Swedish creation of anti-submarine mine and net barriers.

The development was actively promoted by Kofoed-Hansen and Scavenius. They used the German minister, Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau (1869-1928), as a bridge to the German admiralty staff chief, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff (1853-1919). The blocking of the Sound was supplemented by a reinforcement of obstacles in the Great Belt and southwestern Baltic Sea. The Danish vice-admiral also campaigned intensively to make the German Sound guard force strong enough to deter a British cruiser raid meant to assist another submarine force on its way through to the Baltic Sea. He succeeded by making the Germans deploy a pre-Dreadnought battleship and a flying boat tender to beef up its Sound barrier guard force. Kofoed-Hansen also contributed directly to the combined effort. He deployed a Danish submarine division and a naval air flight to the Great Belt Squadron to improve its ability to counter a British attempt to force the mine barrier there.

Early Summer 1916 to Spring 1917: Fall J and Rantzau↑

In early summer 1916, the visible presence of the strong German naval guard force southeast of Copenhagen combined with ever intensifying rumours of an impending British offensive against the Straits. It created near panic in the Danish army, which had not been consulted or informed of Kofoed-Hansen’s campaign. The generals saw that the blocking of the Sound now totally ruled out Danish submarines’ participation in the defence of south-east Zealand, and the cannon of the old German flag battleship threatened Copenhagen with bombardment and the new forward Tune Line defence with a flank attack. In September 1916, a desperate Danish chief of the army general staff bypassed his government to seek support from the British minister in Copenhagen.

In late summer 1916, a domestic political crisis threatened the Danish government, and Rantzau misinformed Berlin that the Danish neutrality line depended on Scavenius remaining in office. To stay in power, the government did not reveal to the German minister the knowledge that the opposition leader, Jens Christian Christensen, was fully behind its pro-German neutrality line.

In Berlin the uncertainty about the Danish neutrality line reinforced the crisis feeling created by the Romanian breach of neutrality, the foreseen effects of a new unlimited U-boat campaign and the notion of increased risks after the Battle of Jutland. The combination brought an end to the German army's veto of planning war against Denmark, which had been in place since February 1905. Now preparations started for the construction of the defence line Sicherungsstellung Nord in North Schleswig. Work started later that autumn.

The war plan against Denmark, Fall J, where the main burden would be carried by the German navy, was signed by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) in December 1916 at a time when the urgency had lapsed. However, in February 1917, the German leadership started to consider both an American and a Norwegian entry into the war, and enemy bases in southern Norway made timely German control of Jutland and Danish waters essential. Fall J was now developed to include a full German army role with the occupation of not only Jutland, but also of various Danish islands outside Zealand. Before Fall J was launched, Denmark would be given five hours to decide her reaction. Rantzau discussed the texts of the potential diplomatic notes to Denmark with Scavenius to get the Danish foreign minister’s comments.

The Danish government reacted to the information about German offensive war preparations by freezing all further defence improvements, such as improved fortifications and additional air defence weapons for Copenhagen. Reductions were planned in the defence budget and the size of the neutrality guard. By reducing the ability to fight any invader, the steps actually made German presence in Danish territory ever more urgent, something duly registered by a resident German assistant naval attaché. The main effect of the government’s defence freeze and reductions was to minimize the army’s ability to resist a German operation against Denmark and thus undermine the deterrence effect it actually did have in relation to Fall J-planning against Copenhagen in fall 1916.

↑

During the spring and early summer 1917, Rantzau fought hard to avoid allowing the notoriously ineffective German intelligence to trigger Fall J with an agent report about an English operation against Jutland, the Straits or Norway. He emphasised that the Danes would fight against the first to invade, and that had to be England to make certain that Denmark would accept German help. If Germany moved on rumours, even following an explanatory ultimatum, the Danes would end up on the side of Germany’s enemies. If, on the other hand, Germany waited for England to be the aggressor, Denmark, and especially her navy, would resist. Thereafter, the Danish army would move aside and give the Germans freedom to fight the British in Jutland. The Danish navy’s surveillance and situation picture of the approaches to the Straits would discreetly be made available. It was a source far superior to the erratic agent observations.

Rantzau got support from the German Foreign Office and, for some months, the admiralty staff accepted the conditions depending on information from Scavenius and the Danish navy. The five hours’ ultimata were dropped as unnecessary, as initial British aggression would make them pointless if Denmark was the target and the need for a German response was obvious, or if Norway was invaded. However, on the morning of 2 November 1917, a successful British light cruiser and destroyer raid into the southern Kattegat hit German shipping there without warning. The raid was partly an extension of the anti-U-boat offensive of the previous months in the south-eastern North Sea, partly what was left of a planned massive raid through the Great Belt to encourage the Russians to continue fighting.

As noted, the Kattegat operation hit the Germans without warning, and Rantzau’s arguments failed to impress upon the admiralty staff that the raid was not the invasion or Strait passage attempt that the Danes were to warn about, and that poor visibility meant that the Danish navy had been as surprised as the Germans. Neither did the post-raid steps taken by Kofoed-Hansen and the Danish Foreign Ministry impress von Holtzendorff. They promised to report all such enemy forces in the future. The trust in Denmark and Rantzau to act in time and in the interest of the German navy had been lost. The German navy thereafter gained freedom by depending on its own intelligence agents.

Adjustment in Winter/Spring 1918 to a German-dominated Danish Future↑

In late December 1917, the German naval attaché to the Nordic States, Captain Reinhold von Fischer-Loßainen (1870-1940), emphasised in his analysis of the situation that the German victory over Russia had made the Baltic Sea a mare clausum, and that it would remain so after the war. The littoral states simply had to adjust to that fact, and this beneficial situation should be used to get Scandinavia under German influence, thus, “Denmark forms the first, nearly completed, phase”.[5]

Then Denmark spoiled part of that winter’s main naval event, the celebration of the successful conclusion of the auxiliary raider, SMS Wolf’s, epic cruise and return to Kiel. In late February, Denmark had interned the part of Wolf’s crew that formed the prize crew of the stranded escorting steamer S/S Ingotz Mendi. Von Holtzendorff was furious and blamed Rantzau for failing to force the Danes not to intern.

The event was probably a key contributing element in triggering the formal decision in Spa on 22 March 1918 to remove any decision to launch Fall J from dependence on intelligence from Danish authorities and from Rantzau’s interference. The Spa decision had been prepared by a visit to Rantzau on 15 March by von Holtzendorff’s chief of operations, Rear-Admiral Freiherr Walter von Keyserlingk (1869-1946). He was Loßainen’s predecessor as naval attaché. He had asked the German minister the impossible question whether the Danes would consider a hypothetical British occupation of the Kattegat Island Samsoe a casus belli that would legitimize German Fall J assistance, or just a serious violation of Danish neutrality.

Now the German minister had become reduced to a channel for demands to the Danes to adjust to what seemed in April to be turning into an early German victory in the West. An unrestrained adaptation to German demands followed. In early April 1918, when a German U-boat stranded in Little Belt and got off without an incident, the Danish navy’s directives were further adjusted in a way that could only benefit Germany. The interned Igodz Mendi prize crew members were released for “home leave” on a threat from the German admiralty staff to block international legal arbitration.

In late April, when Rantzau requested the removal of Captain Erik With (1869-1959), the very effective head of the Danish military intelligence, the Danish government was eager to comply. Neither did the government resist when the Germans wanted the appointment of a new chief of the army general staff who would counter the pro-Entente attitude of most Danish army general staff officers. Fischer-Loßainen was basically correct in his view of the Danish position in relation to a seemingly victorious Germany. Denmark’s government had accommodated German wishes and, via Rantzau, signalled a willingness to accept a military occupation of the main part of the country without any real military resistance.

Conclusion↑

The reason Denmark succeeded in staying out of the First World War was not the balanced policies of its good government. It was a result of strategic choice on the part of Germany and Great Britain, and especially of their armies, not to support the strategic ambitions of their navies in Denmark. No Danes seemed capable of understanding that even mighty Germany had to prioritise its use of limited resources and that Danish security rested on a German army veto against wasting forces in the north until her opponents had violated Danish neutrality. Thus all Danish politicians underestimated the robustness of the country’s neutrality and its freedom of action.

Yet, even if Kofoed-Hansen and Scavenius eagerly sought to please the Germans, their pro-active work to get the Germans to hinder British submarine entry and block a Royal Navy raid was a clear breach of neutrality, and probably therefore not entered into the official narrative. Towards the end of the war, the adjustment of Danish neutrality to open and perceived German wishes brought Denmark very close to the situation that was realised on 9 April 1940.

The Munch-led pursuit of unilateral defence reductions conflicted with the current general view of the obligations of neutral countries and thus weakened national security by what was basically an ideologically nourished experiment. His effort was not supported by public explanations because of the clear conflict with the Defence Laws. However, the main security problem created by the Danish government was its deliberate failure to make clear to Rantzau that the pro-German neutrality line was fully supported by the main opposition leader and thus robust. By increasing the risk of German operations to control Denmark the government triggered the German minister’s help to stay in power.

Michael H. Clemmesen, Royal Danish Defence College

Section Editor: Nils Arne Sørensen

Notes

- ↑ In modern form best represented in: Lidegaard, Bo: En fortælling om Danmark i det 20. Århundrede [The Tale of Denmark in the 20th century], Copenhagen 2011.

- ↑ Beretning fra Kommissionen til Undersøgelse og Overvejelse af Hærens og Flaadens fremtidige Ordning [The Report from the Commission for the Investigation and Evaluation of the future Organisation of the Army and Navy], Copenhagen 1922, Bilag I: Lovene om Hærens og Søværnets Ordning m.m. af 30. September 1909 [Annex I: The Army and Navy Organisation Acts, etc. of 30 September 1909].

- ↑ Best analysed in: Staur, Carsten: P. Munch og forsvarsspørgsmålet ca. 1900-1910 [P. Munch and the Defense Question 1900-1910], in: Historisk Tidsskrift 14/2 (1981).

- ↑ Rigsarkivet (The Danish National Archives), Berlin, diplomatisk repræsentation og militærmission, 1930-1945, Gruppeordnede sager (aflev. 1951), pk. 894, Moltke No. 341 af 30-3-1915 til Udenrigsministeriet; Erik Scavenius Nr. 150 af 15-5-1915 til den Kgl, Gesandt i Berlin; UMN No. 169 af 2-6-1915 til den Kongelige Gesandt i Berlin, Kriegspolitischer Kultur-Ausschuss des Deutsch-Nordischen Ricard Wagner Vereins; Moltke af 20-6-1915 til Herr Erik Scavenius, Udenrigsminister; Erik Scavenius L.No.1653 af 23-6-1915 til velbaarne Hr. Greve C. Moltke.

- ↑ Rigsarkivet (The Danish National Archives), 860, Håndskriftsamlingen, XVI. Danica, Auswärtiges Amt, File 87-88, Abschrift zu A. 49088.17, Marineattaché für die nordische Reiche, Nr. 2663, Stockholm 20-12-1917, Deutschland und Skandinavien. Dänemark bildet dabei die erste, fast schon erreichte Etappe.

Selected Bibliography

- Clemmesen, Michael H.: Den lange vej mod 9. april. Historien om de fyrre år før den tyske operation mod Norge og Danmark i 1940 (The long road towards 9 April. The story about the forty years before the German operation against Norway and Denmark in 1940), Odense 2010: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Clemmesen, Michael H.: Dansk neutralitetshævdelse og krisestyring under 1. Verdenskrig. Fra E.13 over Bjerregård til Igotz Mendi (Danish efforts to uphold neutrality 1914-18), in: Clemmesen, Michael H. / Poulsen, Niels Bo (eds.): Fra Krig og Fred, Odense 2020: Dansk Militærhistorisk Kommissions Tidsskrift.

- Clemmesen, Michael H.: Det lille land før den store krig. De danske farvande, stormagtsstrategier, efterretninger og forsvarsforberedelser omkring kriserne 1911-13 (The small country before the Great War. Danish territorial waters, Great Power strategies, intelligence and defence preparations before, during and after the crises 1911-13), Odense 2012: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Clemmesen, Michael H. / Thorkildsen, Anders Osvald: Mod fornyelsen af Københavns forsvar 1915-18 (Towards the modernisation of the defence of Copenhagen 1915-18), Copenhagen 2009: Statens Forsvarshistoriske Museum.

- Gemzell, Carl-Axel: Organization, conflict, and innovation. A study of German naval strategic planning, 1888-1940, Lund 1973: Esselte Studium.

- Groß, Gerhard Paul / Rahn, Werner (eds.): Der Krieg zur See 1914-1918. Der Krieg in der Nordsee. Vom Sommer 1917 bis zum Kriegsende 1918, Hamburg; Berlin; Bonn 2006: Mittler.

- Kaarsted, Tage: Great Britain and Denmark 1914-1920, Odense University Studies in History and Social Sciences, Odense 1979: Odense University Press.

- Lidegaard, Bo: En fortælling om Danmark i det 20. århundrede (A tale of Denmark in the 20th century), Copenhagen 2011: Gyldendal.

- Lidegaard, Bo, Feldbæk, Ole / Petersen, Nikolaj / Due-Nielsen, Carsten (eds.): Dansk udenrigspolitiks historie. Overleveren 1914-1945 (The history of Danish foreign policy. The survivor 1914-1945), volume 4, Copenhagen 2003: Danmarks Nationalleksikon.

- Paulin, Christian: Veje til strategisk kontrol over Danmark. Tyske planer for et præventivt angreb på Danmark 1916-1918 (Paths to strategic control of Denmark. German plans for preventive attacks on Denmark 1916-1918), in: Historisk Tidsskrift 109/2, 2009, pp. 418-458.

- Salmon, Patrick: Scandinavia and the great powers, 1890-1940, New York 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- Sjøqvist, Viggo: Peter Munch. Manden, politikeren, historikeren (Peter Munch. The man, the politician, the historian), Copenhagen 1976: Gyldendal.

- Sjøqvist, Viggo: Erik Scavenius. En biografi (Erik Scavenius. A biography), 2 volumes, Copenhagen 1973: Gyldendal.

- Staur, Carsten: P. Munch og forsvarsspørgsmålet ca. 1900-1910 (P. Munch and the defence question 1900-1910), in: Historisk Tidsskrift 14/2, 1981, pp. 101-121.