Introduction↑

Regardless of how it is measured, World War I (WWI) had a severe impact on all national economies involved. To be sure, not all of the effects were negative – some economies, such as the North American economies, thrived as a result of the war – but the total effect was undoubtedly negative. The belligerent economies naturally bore the brunt of the economic impact, with the Central Powers Germany and Austria(-Hungary) losing 20 and close to 30 percent respectively of their gross domestic product (GDP) from 1913 to 1918. Entente France and Russia fared no better, with GDP drops of 35-40 percent during the war. Both the United Kingdom and United States of America (USA) did better economically, however, even experiencing positive growth from 1915 to 1918.[1] Total economic losses, although difficult to estimate, including loss of physical capital and human capital, added up to 692 billion US dollars, in 1938 prices.[2] Trade was also disrupted, even though we cannot safely say by how much, due to inflation. Exports from continental Europe were hit the hardest, while imports into Britain (as a share of GDP) only dipped slightly and even increased in France. Exports as a share of GDP rose significantly in Canada and the USA.[3] As expected, the war brought trade between adversaries down to almost zero, while trade between allies and between allies and neutrals (here, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and Sweden) increased sharply.[4] One very poignant effect of the war was that the state’s role in economic activity grew, with government spending as a share of national income growing by a factor of five in belligerent countries.[5] The effects of WWI were also felt in neutral countries, even though the loss of human capital and physical capital was on a much lower scale than for belligerents. This article investigates the economic effects for one such neutral country, Sweden. Section 2 will discuss overall economic development by looking at GDP, foreign trade, and the post-war crisis in 1921-1922. Fiscal policy will be dealt with in section 3, while section 4 looks at monetary policy, price changes, food shortages, and the black market. The last section then concludes the article by putting the Swedish experience in a broader context.

Lost Years: Swedish Economic Development 1906-1925↑

With the outbreak of WWI in 1914, Sweden instantly declared itself neutral and would remain at safe distance from the theatres of war for the remainder of the conflict. Just as WWI broke a general development of sustained economic growth, industrialisation, globalisation, and economic integration, it hindered several positive trends for the Swedish economy. Sweden was a latecomer, but had seen a boost in industrialisation and economic growth since about 1850. Together with Germany and the USA, it had been one of the fastest growing economies in the western hemisphere up until WWI.

The Effects of World War I on GDP↑

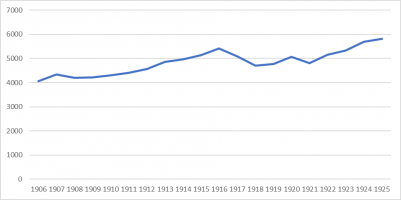

To be sure, the first two years of the war were favourable for Sweden. Economic growth continued at a similar pace as during the previous decade. This came to a screeching halt in 1917 and 1918 when the economy shrunk by 6.1 and 7.6 percent respectively (see Figure 1).[6] It has been estimated that the actual effect of the war on GDP growth rates was positive in the initial stages, contributing 4.74 percent in 1914-1915, but clearly negative in the latter stages and in the aftermath of the war, reducing growth by 5.66 percent in 1916-1917 and by 1.77 percent in 1918-1920.[7] This made Sweden the neutral country with the slowest growing economy (compared with Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) between 1913 and 1929. However, this still put the country above the growth rates of all European belligerents. A large part of this downturn can be explained by the shutting off of foreign trade in 1917 and 1918 and the effects it had, which will be described further in the following section. The economic downturn also made itself known in the financial sector, where loans from commercial banks as a share of GDP decreased from a high point of 67 percent in 1912 to a low of 50 percent in 1916.[8] In relative terms, the negative economic effects of WWI were generally “mild” compared to the experiences of World War II for Sweden and the other Nordic countries.[9] On the plus side, profits in industry overall skyrocketed and led to increasing investments in electricity, power plants, and motors and machinery for industrial production until 1920.[10] Certain companies would also benefit greatly from wartime experiences. One such company was the ball bearings manufacturer SKF whose export, both to belligerents and neutrals, grew substantially during this time. This trend helped to make the company a market leader in the 1920s.[11] The war and the accompanying shutdown of trade affected Swedish businesses in many ways. Many industrialists saw the initial stage of the war as a business opportunity for neutral Sweden. In 1915 alone, seventy-one new companies were registered on the Stockholm stock market, doubling the total number of registered companies. This number increased further up until 1918. Other major structural changes were also underway, as the war period also saw a boom in mergers between companies, with a peak of seventy-nine mergers in 1918. The majority of mergers occurred between companies in the same sector, and the most active were found within the metallurgy, engineering, chemical, and pulp- and paper industries.[12]

Figure 1: GDP per Capita 1906-1925 in 2011 PPP-adjusted US Dollars[13]

The Development of Foreign Trade↑

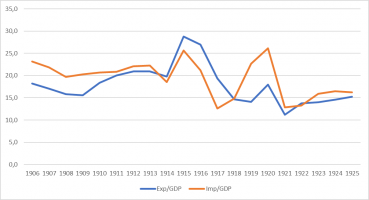

As with GDP, the first half of WWI was beneficial for Swedish foreign trade, as both export and import levels jumped from 1914 to 1915. The war also shifted the balance of Swedish trade, turning an import surplus into the largest export surplus the country had seen for decades. Things changed dramatically in 1917 when German submarine warfare started targeting neutral merchant vessels, many Scandinavian ones among them. This, together with the general escalation of warfare, meant that Swedish trade levels dropped dramatically. The loss of exports was particularly sharp, but it was almost on an equal scale for imports from 1916 to 1917. Total trade as a share of GDP dropped almost by half from 1916 to 1918 (see Figure 2). Such a loss of trade had not been experienced in Sweden since the 18th century. Additionally, a total of 280 Swedish merchant ships were lost and more than 250,000 gross registered tons of shipments were destroyed. These losses were heavy, but paled in comparison, particularly with the losses of the Norwegian merchant navy.[14] The government tried to spur continued access to foreign goods by eliminating tariffs on agricultural imports such as grains, dairy, and pork toward the end of the war. Tariffs were also lowered on long-distance imports such as sugar, tobacco, coffee, and tea.[15] However, these trade policy changes were probably not enough to ensure continued flows of foreign foodstuffs into the country. The war also changed the composition of the country’s bilateral trade. Two major trends are discernible: first, after decreasing imports from the central powers in 1914 and 1915 (in favour of American imports, which doubled), the share of trade from Germany and Austria increased from 1916-1918. The countries in the Entente (primarily the United Kingdom) had contributed about a third of Swedish imports before the war, but in 1917-1918 that share was cut by more than a third. Exports followed a similar pattern. The trade turn towards the Central Powers would spell political problems for the government and was a contributing factor to the loss in the 1917 parliamentary elections. Second, bilateral trade towards the end of the war was also increasingly oriented towards the other neutral countries, and more than anything became more intra-regional. Trade with Denmark, Finland, and Norway had made up about 15-20 percent of the total before the war, but increased to over 30 percent in 1917-1918. Trade with the other neutrals, the Netherlands and Switzerland, also rose during these years, but by a smaller amount. Trade relations with the United Kingdom returned to pre-war levels in 1919. Trade with the Nordic countries and USA increased during the 1920s, but it decreased with Germany.[16]

Figure 2: Exports and Imports as Share of GDP, 1906-1925[17]

Post-war Crisis↑

The economy picked up in 1919 as trade, mostly imports, increased. Life slowly regained some normality and growth in 1920 was a full 6.3 percent. However, as can be seen in Figure 1, GDP was hit with a downturn once again in 1921. The effect of the crisis wasn’t as severe as during 1917 and 1918, but it was the largest contraction of the economy before 1945 that was not directly connected to war and crop failures – at 5 percent negative change from 1920 to 1921.[18] As can be seen in Figure 2, the export sector was dealt a hard blow, but total industrial output and domestic investment also dropped dramatically. This crisis was characterised by deflation rather than inflation. The Consumer Price Index dropped by some 90 percent from 1920 to 1922, which contributed to a banking crisis. Share prices fell and it was more difficult to borrow from the central bank than it had been previously, which further restricted banks’ ability to lend. The number of active commercial banks had decreased by more than half during this extended crisis, reducing from 75 in 1913 to 32 in 1924. Many smaller and medium-sized banks went bankrupt and/or were bought up or merged with the large banks, leading to a sharp increase in market concentration in the financial sector. Other than the banks, the sectors that were hit the worst were those which had benefitted the most during WWI, such as the iron and steel industries, as well as saw mills. The war had created a bubble which could not be sustained once international competition picked up and demand for Swedish goods on international markets decreased again. Further evidence for this bubble was that speculation and increased activity led to a red-hot Stockholm stock market, which, in 1918, reached a high point it wouldn’t see again until the 1980s. Although the crisis was severe, it was short-lived. Economic growth had already picked up again in 1922-1923, and remained high and sustained throughout the 1920s. One lingering negative effect of the crisis was unemployment, which, among union members, mostly in construction and manufacturing, increased from 4-5 percent to 25 percent and remained at a high level throughout the 1920s.[19]

Revenue Crisis Averted↑

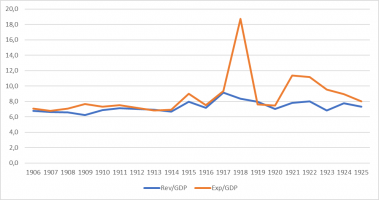

Up until 1914, Sweden had been dependent on taxes from foreign trade to a substantial degree. During the decade leading up to WWI, customs revenue (from taxes on imports) made up close to 30 percent of total government revenue.[20] This came to create challenges for the government when trade was severely cut in 1917 and 1918. In these two years, customs revenue, as a share of total government revenue, plummeted to historically low levels, making up only 7 and 5 percent, respectively.[21] Increasing military expenditure put the government under pressure to find alternative sources of revenue. Because of shortages of alcohol and sugar, specific consumption taxes on these goods, which had been a large source of revenue before the war, also plummeted. This loss was partly offset by a new excise on tobacco, which was introduced in 1915. What increased most sharply were taxes on income at the state and local level, the former having been introduced only in 1903. At the peak of the war, these taxes came to make up close to a full 80 percent of the total, a figure not reached before or after.[22] Part of the reason for this increase was that taxes on higher income and capital, intended to cover increasing military expenditure, were introduced in 1915. Around a third of the 75 million SEK that were collected from these extraordinary taxes came from companies. Marginal tax rates also increased during the war. Some of these increases were supposed to be temporary, but some remained even when peace was restored. The war effectively eliminated Sweden’s foreign debt, which was over 80 percent of GDP in 1914, but dropped to just around 20 percent in 1920.[23] Instead, the government was forced to borrow domestically, pushing public debt from below 3 percent of GDP in 1916 to over 30 percent in 1919.[24] The increase in income taxation and domestic borrowing led to increases in both government revenue and expenditure (see Figure 3). The gold standard was not in effect during the war, so the Swedish krona floated freely. As an effect of this, the Swedish exchange rate appreciated in value against the British pound and the US dollar. This was, however, short-lived, as in both cases the krona depreciated again after 1918. The war also effectively “dealt the death blow” to the Scandinavian Monetary Union (SMU), where the central banks in the three Nordic countries clashed over how to deal with the gold situation. Sweden tried unsuccessfully to push for a gold blockade, while Denmark and Norway, which had seen less inflow of gold during the first half of the war, opposed it. The situation eventually blew up in 1917 as conditions worsened overall, effectively suspending the SMU, which had, up to that point, been “arguably the most effective European monetary union.”[25]

Figure 3: Government Revenue and Expenditure as Share of GDP, 1906-1925[26]

Prices and Food Shortages↑

Prices increased rapidly during the war, going up by some 240 percent from 1914 to 1918. They then rose slightly more until 1920, before a marked downturn. Eli Heckscher (1879-1952) argued that the government, through the central bank, had worsened the situation with its monetary policy, by increasing the money supply at a time when the supply of goods was decreasing heavily.[27] Nominal wages couldn’t keep up with inflation, so real wages overall saw a sharp downturn. The downturn in imports from 1916 caused a shortage of foreign foodstuffs, which was exacerbated by poor harvests in 1917, leading to a full-scale food shortage. In 1917-1918 the disposable amount of wheat and rye per capita was at 83 kilograms, while it had been a full 183 kilograms between 1910 and 1914.[28] The government was forced to ration bread, flour, and sugar. This was later extended to other staple foods such as milk and potatoes. A notable side effect of this was that alcohol consumption decreased sharply in 1917 and 1918, as imports of foreign wine and spirits dwindled and materials for beer breweries couldn’t be shipped in. Official numbers on consumption show a decrease of more than 75 percent, in litres of pure alcohol per capita, and almost zero consumption of beer in 1917 and 1918.[29] There was also a severe fuel shortage towards the end of the war, as coke and coal could no longer be imported from Germany. This affected Stockholm and southern Sweden more than the northern parts, since the latter could stockpile wood to a larger degree. According to Lennart Schön (1946-2016), many citizens “were forced to buy wood at high prices on the open market”.[30] Some were able to profit from the severity of the shortages, as rationed food and fuel were being sold at high prices on the black market. Meanwhile, social tensions were high and the capital was plagued by food riots, protests, and demonstrations. Demonstrations were particularly prevalent in all parts of the country in April 1917. A total of nearly 200,000 people participated over only ten days. Bakers who had sold grain and bread on the black market were particular targets for the rage of the people and were called “bread barons” during these years. These food riots are some of the most written about and well known food crises in Swedish history.[31] To make matters worse, the cities were characterised by housing shortages as the war markedly decreased construction, while urbanisation continued.

Conclusion↑

The Swedish experience during WWI is usually described as one of two halves. The first two years were characterised by increased trade and GDP, and industrial and financial growth. Things quickly turned in 1917 when trade was shut off, and Sweden went into a recession followed by sharp price increases, food shortages, rationing, and food riots and protests all across the country. Given the magnitude of the recession, its effects, and the post-war crisis it led to, one would have to agree with Schön and Peter Hedberg that the economic effects of WWI were overall undoubtedly negative for Sweden.[32] However, it is important to keep in mind that even though the negative economic effects were significant and felt by a large share of the population, they were not on the same scale as those experienced in belligerent countries. Sweden’s economic performance was still above that of all European belligerents, and if we add human costs, this difference is greater still. In conclusion, WWI even had detrimental consequences for neutral countries, but neutrality did mitigate a portion of those repercussions.

Henric Häggqvist, Uppsala University

Section Editor: Lina Sturfelt

Notes

- ↑ GDP figures from Broadberry, Steven / Harrison, Mark: The Economics of World War I. An Overview, in: Broadberry, Steven / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, Table 1.4.

- ↑ Ibid., Table 1.13.

- ↑ Findlay, Ronald / O’Rourke, Kevin H.: Power and Plenty. Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium, Princeton 2007, p. 433.

- ↑ Gowa, Joanne / Hicks, Raymond: Commerce and Conflict. New Data about the Great War, in: British Journal of Political Science 47/3 (2017), pp. 653-674.

- ↑ Broadberry / Harrison (eds.), Economics 2005, Table 1.5.

- ↑ Bolt, Jutta et al.: Rebasing “Maddison”. New Income Comparisons and the Shape of Long-run Economic Development, in: GGDC Research Memorandum 174 (2018).

- ↑ Hedberg, Peter: The Impact of World War I on Sweden’s Foreign Trade and Growth, in: The Journal of European Economic History 45/3 (2016), Table 2, p. 98.

- ↑ Larsson, Mats / Häggqvist, Henric: The Balance of Imbalance between Deposits and Lending in Swedish Commercial Banking, 1870-1994, in: UPIER Working Paper 5 (2018), Figure 1.

- ↑ Lennard, Jason / Golson, Eric: The Macroeconomic Effects of Neutrality: Evidence from the Nordic Countries during the Wars, in: Eloranta, Jari et al. (eds.): Small and Medium Powers in Global History. Trade, Conflicts, and Neutrality from the 18th to the 20th Centuries, New York 2018, pp. 196-212.

- ↑ Schön, Lennart: Sweden’s Road to Modernity. An Economic History, Stockholm 2010, p. 236.

- ↑ Golson, Eric / Lennard, Jason: What was the Impact of World War I on Swedish Economic and Business Performance? A Case Study of the Ball Bearings Manufacturer SKF, in: Eloranta et al. (eds.), Powers 2018, pp. 173-195.

- ↑ Larsson, Mats: Krig, kriser och tillväxt 1914-1945 [War, Crises and Growth 1914-1945], Stockholm 2019.

- ↑ Source: Bolt, Jutta et al., Rebasing “Maddison” 2018.

- ↑ Søndergaard Berndtsen, Bjarne: Neutral Merchant Seamen at War. The Experiences of Scandinavian Seamen during the First World War, in: Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the War Experience of the Northern Neutrals, Lund 2012, pp. 327-354.

- ↑ Hedberg, Peter / Häggqvist, Henric: War Time Trade and Tariffs in Sweden from the Napoleonic Wars to WWI, in: Eloranta et al. (eds.), Powers 2018, p. 131.

- ↑ Bilateral trade data from Dedinger, Beatrice / Girard, Paul: Exploring Trade Globalization in the Long Run. The RICardo Project, in: Historical Methods. A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 50/1 (2017), pp. 30-48, and Mitchell, Brian R.: International Historical Statistics. Europe, 1750-2000, New York 2003.

- ↑ Source: Schön, Lennart / Krantz, Olle: New Swedish Historical National Accounts since the 16th Century in Constant and Current Prices, in: Lund Papers in Economic History 140 (2015), Table I and Table VIIa.

- ↑ Schön, Road to Modernity 2010, p. 247.

- ↑ Unemployment in the total workforce (including the non-unionised) was, however, lower. Ibid.

- ↑ Häggqvist, Henric: Foreign Trade as Fiscal Policy. Tariff Setting and Customs Revenue in Sweden, 1830-1913, in: Scandinavian Economic History Review 66/3 (2018), pp. 298-316.

- ↑ Hedberg / Häggqvist, War Time Trade 2018, p. 133.

- ↑ Henrekson, Magnus / Stenkula, Mikael: Swedish Taxation since 1862. An Introduction and Overview, in: Henrekson, Magnus / Stenkula, Mikael (eds.): Swedish Taxation. Developments since 1862, New York 2015.

- ↑ Schön, Road to Modernity 2010, Figure 4.2, p. 241.

- ↑ Jorda, Oscar / Schularick, Moritz / Taylor, Alan M.: Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts, in: Eichenbaum, Martin / Parker, Jonathan A. (eds.): NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016, volume 31, Chicago 2017.

- ↑ Rongved, Gjermund F.: Money Talks. Failed Cooperation over the Gold Problem of the Scandinavian Monetary Union during the First World War, in: Ahlund (ed.), Scandinavia 2012.

- ↑ Source: Mitchell, B. R.: International Historical Statistics. Europe, 1750-2000, New York 2003, Tables G5 and G6; Schön / Krantz, Accounts 2015, Table I.

- ↑ Heckscher, Eli (ed.): Bidrag till Sveriges ekonomiska och sociala historia under och efter världskriget [Contribution to the Economic and Social History of Sweden during and after the World War], Stockholm 1926, p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 6.

- ↑ It is likely that official numbers overestimate the sharp drop in consumption, as brewing and distilling in homes and sales in black markets could have been sustained at least at some level.

- ↑ Schön, Road to Modernity 2010, p. 240.

- ↑ Nyström, Hans: Hungerupproret 1917 [The Hunger Uprising of 1917], Ludvika 1994; Carlson, Gösta / Larsson, Roland: Brödupploppet i Göteborg 1917 [The Hunger Riot in Gothenburg 1917], Göteborg 1997.

- ↑ Schön, Road to Modernity 2010; Hedberg, Impact 2016.

Selected Bibliography

- Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the war experience of the northern neutrals, Lund 2012: Nordic Academic Press.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Häggqvist, Henric / Hedberg, Peter: Wartime trade and tariffs in Sweden from the Napoleonic Wars to World War I, in: Eloranta, Jari / Golson, Eric; Hedburg, Peter et al. (eds.): Small and medium powers in global history. Trade, conflicts and neutrality from the 18th to the 20th centuries, London 2018: Routledge, pp. 116-138.

- Heckscher, Eli F. (ed.): Bidrag till Sveriges ekonomiska och sociala historia under och efter världskriget (Contribution to the economic and social history of Sweden during and after the world war), Stockholm 1926: P. A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag.

- Hedberg, Peter: The impact of World War I on Sweden's foreign trade and growth, in: Journal of European Economic History 45/3, 2016, pp. 83-103.

- Schön, Lennart: Sweden's road to modernity. An economic history, Stockholm 2010: SNS Förlag.

- Schön, Lennart; Krantz, Olle: New Swedish historical national accounts since the 16th century in constant and current prices, in: Lund Papers in Economic History 140, 2015.