Introduction↑

The central propaganda institution of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces during World War I was the War Press Office, or Kriegspressequartier (KPQ), a subsection of the staff of the Commander in Chief (k.u.k. Armeeoberkommando, or AOK). The KPQ organized and performed propaganda activities, and exercised censorship on the front lines (Armee im Felde). In contrast to other important war organizations, the KPQ was not primarily a supervisory authority but an executive body. In accordance with an instruction issued by the Ministry of War in 1909, the KPQ was prepared for the possibility of mobilization. On 28 July 1914, the KPQ was mobilized, and by early August 1914, its first employees were recruited in Vienna. In August 1914, the staff of the KPQ amounted to just fifty-one persons, however, this number climbed to 925 persons by the end of the war. In the very beginning, only writers and journalists for foreign and domestic newspapers were engaged as war correspondents for the KPQ, but soon visual artists, photographers, filmmakers, theatre people and musicians were added.

In addition, the KPQ organized propaganda trips to neutral states and occupied territories. For propaganda activities abroad, diplomatic missions, military attachés, and the German War Press Office (Kriegspresseamt), with its respective liaison officers, played an important role. The Press Officer of the AOK, Edmund Glaise von Horstenau (1882–1946), had a major impact on the KPQ. He prepared drafts for official reports and press-communiqués.

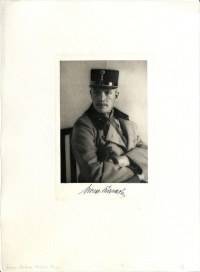

Under the command of Maximilian von Hoen, 1914-1917↑

The commander of the KPQ during the first years of the war was Maximilian Ritter von Hoen (1867-1940), who was a General Staff Officer and military historian. From August 1914 to March 1917, he was commander of the KPQ. From 1 January 1916, he took on additional responsibility as the Director of the War Archives.

In March 1917, on the orders of Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922), General Hoen resigned from his command of the KPQ. At the same time several war correspondents and war painters were called to duty in the fire trenches. Only people who were unfit for service were allowed to be accepted in the KPQ at this time, but in practice, there were many exceptions. Thus, the KPQ acquired a dubious reputation as a collection point for so-called “patriotic shirkers”.

Due to this fact, on 19 and 21 March 1917, by order of Emperor Charles, two large-scale and rigorous musters took place in all KPQ offices. The writings of Edmund Glaise von Horstenau, the press officer of the AOK, and Karl Lustig-Prean (1892-1965), the aide-de-camp of the KPQ, presented this procedure to have had a “cabaret-like” character. Antisemitism also appeared to play a role, evidenced by the fact that many of the “shirkers” identified were Jewish and belonged to the so-called “coffeehouse writers”. Consequently, these events were humorously referred to by Glaise von Horstenau as Osterpogrom (the Easter Pogrom).

Under the command of Wilhelm Eisner-Bubna, 1917-1918↑

Hoen’s successor until the end of the war was the General Staff Officer, Wilhelm Eisner-Bubna (1875–1926). In the first years of the war he served at the Galician and Italian fronts. Due to stress and overexertion, he was transferred to the KPQ and was appointed as its Commander on the 16 March 1917. He extended the KPQ and formed a strictly organized body, a propaganda centre. His key message was: “press-service is propaganda-service”. Under his command, the KPQ took over the Executive Press Service of the AOK.

Responsibilities of the KPQ↑

War Correspondents↑

Numerous writers and journalists from Austria-Hungary, the allied Central Powers and the neutral states worked for the KPQ on behalf of their newspapers. Among them were various well-known authors as Ludwig Biró (1880–1948) for Pester Lloyd, Sven Hedin (1865–1952), Ludwig Hirschfeld (1882–1945) for Berner Tagblatt, Egon Erwin Kisch (1885-1948), Robert Michel (1876-1957), Ferenc Molnár (1878–1952) for As Est, Leo Perutz (1882–1957), Alexander Roda Roda (1872–1945) for Neue Freie Presse, Union Stuttgart, Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, Pester Lloyd, and Vossische Zeitung, Alice Schalek (1874–1956) for Neue Freie Presse, Hugo Schulz (1870-1933) for Arbeiterzeitung, and Margit Vészi (1885–1961) for Pester Lloyd. Some authors, for example Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874–1929), Ludwig Ganghofer (1855-1920), Robert Musil (1880-1942) and Franz Werfel (1890–1945), were only temporarily engaged for particular projects.

During the first month of the war, the AOK kept the correspondents well away from the front lines and the fire trenches. Their primary job was to embellish the official communiqués of the AOK. Most intellectuals agreed with the common, professional “war howl” exhibited by the writers. One important exception was Karl Kraus (1874–1936), who criticized the propaganda jargon used by the war writers, including the war-glorifying diction and patriotic beautification of their reports.

Throughout the course of the war, war correspondents were also engaged closer to the front. The KPQ organized trips and guided tours to the front lines, while maintaining a secure distance from the combat zones. In addition, the KPQ established field offices (Exposituren), where a certain number of war correspondents were put under the command of an officer on the front lines for brief periods.

War Painters↑

Soon after the beginning of the war, not only writers and journalists were engaged as war correspondents, but also fine artists and war painters. Altogether, between 150 and 160 painters and sculptors were involved, including well-known talents such as Albin Egger-Lienz (1868–1926), Ludwig Hesshaimer (1872–1956), Stephanie Hollenstein (1886–1944), Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980), Alexander Pock (1871–1950), Fritz Schönpflug (1873–1951), and Roland Strasser (1892–1974).

The artists worked in the Art Department (Kunstgruppe) of the KPQ, which was led by Dr. Wilhelm John (1877–1934), who was also acting as the Director of the Army Museum (Heeresmuseum) in Vienna. In contrast to the war correspondents, the war painters and war photographers had to work on the front lines in order to sketch their impressions. Afterwards, they would complete their paintings or pictures in their workrooms, away from the front. According to the “Regulations for Visual Reports in War Times” (Vorschrift für die bildliche Berichterstattung im Kriege), each of them had to deliver one sketch per week from their activities on the front, and one painting per month from their work in the atelier.

Propaganda↑

During the first years of the war, responsibility for photo propaganda was decentralized across several institutions. Eisner-Bubna, who was himself an amateur photographer, centralized the official photo-propaganda service under the supervision of the KPQ. For this purpose, he separated a slide photography unit (Lichtbildstelle) from the Art Department (Kunstgruppe), which was hitherto responsible for painting and photography.

During the first years of the war, film-propaganda was co-ordinated by the War Archives. Captain resp. Major Karl Zitterhofer (1874–1939) acted as Film Officer (Filmreferent) of the Kriegsarchiv, while also acting as a military historian. First external companies, including the Wiener Kunstfilm-Industrie-Gesellschaft, the Österreichisch-Ungarische Kino-Industrie-Gesellschaft and the Sascha-Filmfabrik of Alexander Graf Kolowrat-Krakowsky (1886–1927) produced the films. In May 1917, film production was centralized under the KPQ. Field offices and film squads were composed to conduct film shoots. Each squad consisted of one operator and two assistants, and would work for a period of four to six weeks at a time on the front lines.

The KPQ was also responsible for defending against enemy propaganda for most of the war, but in summer of 1918, the staff of the Commander in Chief established a separate Office of Enemy Propaganda Defence (Feindpropaganda-Abwehrstelle, or FASt), under the command of Colonel Egon Freiherr von Waldstätten (1875–1951).

Conclusion↑

The longer the war dragged on without visible military success, the more powerful the KPQ’s propaganda machinery and the variety of its products grew. Eventually, the media activities of the KPQ concentrated not just on newspaper journalism and daily reports, but also on print works and periodicals published by the KPQ itself. Most important was a publication called the “Austro-Hungarian War Correspondence” (Österreichisch-Ungarische Kriegskorrespondenz), a kind of press folder, published throughout 1917 and 1918 several times a month. This publication was geared towards the foreign press and diplomatic representatives of the Central Powers and the neutral states. Eisner-Bubna was particularly proud of the illustrated booklet La Marche sur Trieste (The March on Trieste), published in 1917 in French. The various branches of the KPQ compiled press reviews from domestic and foreign newspapers, produced reports and press information, organized lectures on various topics, especially to stimulate the subscription of war bonds. The KPQ organized more than forty exhibitions throughout Austro-Hungary, the Central Powers and the neutral states. War photographers and war correspondents produced hundreds of thousands of photographs. War cinematographers produced uncountable meters of film for cinemas on the front lines and in the hinterland.

Although the KPQ was a huge organization, it lagged far behind compared to the efficacy of the Allied propaganda industry, especially the British Ministry of Information. The reason for this imbalance was the lack of participation of civil society in the development of information policy. Also, rigorous censorship, initiated by the anxious High Commander Eisner-Bubna had overly ambitious plans for his gigantic propaganda institution. Following the example of other belligerent states, he had plans to turn the KPQ into a “Ministry of Information” after the war, however, this plan was never realized. On 15 December 1918, the KPQ was dissolved.

Christoph Tepperberg, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Broucek, Peter: Das Kriegspressequartier und die Literarischen Gruppen im Kriegsarchiv 1914-1918, in: Amann, Klaus / Lengauer, Hubert (eds.): Österreich und der Grosse Krieg, 1914-1918. Die andere Seite der Geschichte, Vienna 1989: C. Brandstätter, pp. 132-139.

- Cornwall, Mark: The undermining of Austria-Hungary. The battle for hearts and minds, New York 2000: St. Martin's Press.

- Džambo, Jozo (ed.): Musen an die Front! Schriftsteller und Künstler im Dienst der k.u.k. Kriegspropaganda 1914 - 1918. Begleitband zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung, Munich 2003: Adalbert-Stifer-Verein.

- Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total war and everyday life in World War I, Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press.

- Mayer, Klaus: Die Organisation des Kriegspressequartiers beim k.u.k. Oberkommando im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, thesis, Vienna 1963: Universität Wien.

- Tepperberg, Christoph: Krieg in der öffentlichen Meinung. 'Dichtdienst' und 'Heldenfrisieren' – Kriegspressequartier und Kriegsarchiv als Instrumente der k. u. k. Kriegspropaganda 1914-1918, in: Kropf, Rudolf (ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg an der 'Heimatfront'. Tagungsband der 33. Schlaininger Gespräche, Eisenstadt 2014: Amt der Burgenländischen Landesregierung, pp. 291-304.