Introduction↑

Despite the inconceivably vast number of studies on the First World War, which saw a spike in publications on the occasion of its centenary year in 2014, there is no monograph that focuses in detail on the development of antisemitism during the war and in the early postwar years, neither regionally, nationally nor for Europe as a whole. While studies on the history of antisemitism in individual countries generally deal with the period of the First World War, far too little consideration is given to the specifics of the period overall. A few exceptions aside, even more recent comprehensive studies on the history of the Great War, reveal a surprising lack of deliberation on the presence of antisemites on the political stage. Individual studies that focus on this aspect are few and far between.

When a study deals with the transformation of antisemitism over the course of the war, this occurs, paradoxically, not in portrayals of general history but in works on Jewish history. Moreover, there are glaring differences in the state of research on different countries in Europe: while there are in-depth monographs, edited volumes, and detailed journal articles dealing with the history of German and Austrian Jews during wartime, the number of studies on other European countries is sparse. Brief references to the particularities of antisemitism can be found in general accounts of Jewish history.

The aim of this article is to retrace the development of antisemitism in the European context. Taking a comparative perspective, the article examines whether a form of extreme antisemitism emerged during the war, and, if so, when and where specifically; moreover, what differences can be observable between developments in the Central and the Allied Powers, and what impact did the ensuing revolutions and counterrevolutions have on the radicalization of antisemitism.

Antisemitism in the Prewar Period↑

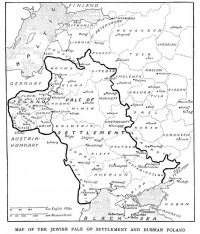

By the end of the 19th century, the demand for full Jewish emancipation was met by almost all European states with the exception of the Russian Empire and Romania. In the wake of the stock market crash of 1873, which triggered a fear of impending crisis and the disintegration of the old order amongst the middle classes, the social climate changed dramatically. A diffuse aversion to Jews became rampant, until, in the fall of 1879 in Berlin, the term “antisemitism” surfaced, encapsulating these anti-Jewish resentments virulent in parts of the population. Antisemitism now took the shape of a distinct social and political movement anchored in a mood widespread in society and thus entering into European politics. Antisemitism became a “cultural code” to which the middle classes and conservative-minded sections of the population in many European countries adhered.[1] Antisemites initiated close transnational contacts and antisemitic ideas began to circulate in their informal networks; and yet, at this point, they failed in their attempts to form a European-wide movement.

The virulence of antisemitism and the public prominence of antisemites varied greatly in individual European states before the First World War. Contemporary observers gauged the situation in the Russian Empire and Romania as especially problematic. In both countries, Jews were denied full civil and political equality. In addition to these countries, there was a second group where the situation was ambivalent: antisemitic convictions had gained a foothold in certain socio-cultural milieus and antisemitic political parties, organizations, and publishers were active, but was unable to gain cultural hegemony. Along with Germany and France, Bulgaria and Greece belonged to this category. Within the Habsburg Monarchy, which overall is to be counted in this group, the situation varied enormously.

In a third group of countries, anti-Jewish attitudes and sentiments were far less widespread in society and there was thus either a complete absence of antisemitic movements or those that did emerge remained weak. Italy, Belgium, Britain, and Serbia belong to this group. To be sure, at the end of the “long” nineteenth century, antisemitism was a European phenomenon on the one hand, but on the other, contemporary observers believed that it could be effectively combated.

Antisemitism at the Outbreak of the War↑

In all warring states, the war was presented to the population as a result of enemy aggression and thus proclaimed to be conducted in self-defense. The ruling classes proclaimed a party truce – “Burgfrieden” or “union sacrée”. In large parts of Europe, it seemed at first as if this stance could signal the end of Jewish exclusion. For their part, in some places – for example in Germany, the Habsburg Monarchy, and France – many Jews saw the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and become fully integrated into society, a strong motivating factor behind so many Jews volunteering for military service. At the same time, in the multinational Habsburg Empire for example, those striving to achieve independence, such as the Czechs, saw this patriotic commitment as support for the German side, a perception that stirred anti-Jewish resentment.

As the war progressed, the opposing camps in the conflict recognized the political and propaganda potential in promising emancipation for the Jews and hence exploited it for their own ends. Both the Central Powers as well as the Allies presented themselves as powers willing to protect Jews or other oppressed minorities and demonstrated the moral superiority of their alliance to the world at large.

Motivated by these foreign and domestic policy considerations, the German and the Austro-Hungarian governments sought to suppress antisemitism. To tap into the financial and intellectual resources of the Jewish population, prominent Jews like Walther Rathenau (1867-1922), Albert Ballin (1857-1918), and the chemist Fritz Haber (1868-1934) were appointed to leading positions in the war economy, the diplomatic service, and scientific research. The central office for war production (Haditermény Rt.) in Hungary was run essentially by Jewish economists. As far as foreign policy was concerned, it was hoped that the domestic “truce” would be welcomed by Jews in the United States and the Russian Empire. In response to the “Ostjuden” (“Eastern Jews”) question and the effort to gain influence in the United States, German authorities were willing to work closely with Jewish organizations. With a few prominent exceptions, the German and Austrian Jewish communities enthusiastically supported the war and displayed a high degree of “self-mobilization”.

Although the German government initially intended to maintain the domestic “truce” and eliminate antisemitism from the public stage through censorship, signs of its revival were already discernible at the end of 1914. The more difficult the situation of the Central Powers became, the more ground the political right gained for anti-Jewish agitation. In the radical antisemitic journal Hammer, the “Eastern Jew question” figured prominently as early as 1914. Antisemitism also reemerged early on in the aristocratic officer corps and the military administration; the number of Jews promoted to the ranks of commissioned and non-commissioned officers declined noticeably.

The situation of Jewish soldiers in Imperial Germany was fundamentally different than that in the Habsburg Monarchy. The army in the multinational Habsburg Empire had an integrative function. Jews were over-proportionately represented amongst reserve officers in particular. Unlike in Germany, antisemitism was not a serious problem in the Austro-Hungarian army. Moreover, censorship was more stringently imposed during the first three years of the war in Austria as the government did not wish to endanger Jewish support for the campaign against Russia. In the Hungarian part of the Habsburg Monarchy, the initial acceptance of the “truce” in domestic politics by the Jewish population was based on its relatively extensive social and political integration. Here Jews occupied the highest positions in political life: the Jewish politician Ferenc Heltai (1861-1913) was mayor of Budapest when the war broke out and the Hungarian war ministry was headed by the converted Jew Samuel von Hazai (1851-1942).

The politics of “union sacrée” also found broad approval in France. The national emergence, which included the Jewish population and the Catholic Church as well as the socialist workers’ movement, gave the French Republic a new foundation. Even the antisemitic journal L’Action française backed the “union sacrée”, generally refraining from attacking the Republic and Jews for the duration of the war. While defeatism and treason were denounced, passages of antisemitic invective were limited to reports on specific Jews who had business connections with Germany or were profiting from the war. In 1917, the chairman of the rightwing, antisemitic Ligue des Patriotes, Maurice Barrès (1862-1923), even included the Jews in the “Diverses Familles spirituelles de la France” (“France’s diverse spiritual groups”).[2]

In Britain, doubt was cast on the loyalty of German-Jewish immigrants: “Anti-German and anti-Jewish stereotypes merged in the general hysteria enveloping British society at the beginning of World War I.”[3] Another area of conflict were the social and cultural tensions between the local populations and Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Stereotypes, such as criminality, clannishness, fraudulence and fast practice, materialism, and disloyalty to national interests, were pinned onto these poor immigrants who were considered unfair competitors for limited housing and employment. However, with the exception of the British Brothers’ League founded in 1901, which took a xenophobic position towards all immigrants in London’s East End and was openly antisemitic, no specifically antisemitic organization was active in Britain before the end of the First World War.

Although the military leadership in the Russian Empire considered Jews to be “unreliable” soldiers when it introduced compulsory military service in the 1870s, a total of 600,000 Jewish soldiers were recruited into the Russian army.[4] Here many Russian farmers and workers encountered Jews for the first time and many were overcome with a feeling of the “foreignness” of these Jews. Given the Germanophobia that prevailed at the outbreak of the war and widespread antisemitism, Germans and Jews living in border regions were viewed as potential traitors and spies. They were accused of conspiracy and treason, and often fell victim to violence.

In Serbia and Belgium, the first two battlefields of the war, various sections of the population, including Jews, were brought together to form a strong national alliance. Not only were Jews a small minority in both countries, but, moreover, antisemitic attitudes and sentiments were not widespread. What distinguished this war from preceding conflicts was that it also intentionally targeted the civilian population. This had disastrous consequences in Galicia and Bukovina where Jews made up a large portion of the population and which had been conquered and reconquered by the opposing armies of the Tsarist Empire and the Central Powers. Thus, a large number of Galician Jews fled to the Austrian interior and other parts of the Habsburg Empire where some of them were held in refugee camps, the so-called “Barackenlager”.[5]

Rising Antisemitism during the War↑

Already in the fall of 1914 it was apparent that the expectations of the Central Powers of a quick victory were dashed. As 1915 unfolded and confidence in victory dwindled, compounded in turn by a worsening supply situation at home, antisemitic agitation by rightwing extremist and völkisch organizations rose, foremost in Germany but also in Austria-Hungary.

In the German Reich, these rightwing organizations submitted a flood of petitions to the Prussian War Ministry warning of Jewish “draft dodgers” and demanding a statistical survey of Jewish participation in the war and active contribution on the home front. The disastrous events of 1916, the battles of Verdun and Somme in the West and the Brusilov Offensive in the East, further intensified antisemitic agitation. Eventually, the German War Ministry caved into the pressure from the right and ordered a “Judenzählung” (Jewish census) in October 1916, a statistical survey of Jewish involvement on the front. Austrian antisemites pursued the same strategy, albeit their demands for a headcount were not met. The optimistic expectations of large sections of the Jewish population in Germany were dashed. Although recent studies have questioned whether this disappointment was as great as later recollections claimed, there is no doubt that the German-Jewish press discussed this event at length.

In the German Reichstag, Social Democrats and the Progressive People’s Party protested against the order, while many camps within German Judaism fought the insinuations of the census. In response, the War Ministry was forced to formulate a supplementary decree, pointing out that the census was not an authorization to remove Jews from their current positions. In addition, the War Ministry issued a “declaration of honor” and refrained from publishing the results of the “Jewish headcount”. This opened the way for even more antisemitic insinuations and would result in a bitterly fought public controversy at the end of the war on the involvement and contribution of Jews. As for the question of whether there was a noticeable isolation of Jewish comrades amongst ordinary soldiers, sources give a “conflicting impression”, for Jewish soldiers only occasionally mentioned experiencing antisemitism in their letters home.[6]

With the increasingly acute food shortages of the “turnip winter” of 1916-1917, the antisemitic mood spread to the “home front”, with Jews cast as “racketeers” and “war profiteers”. The agitation of völkisch, antisemitic organizations in the German Reich inflamed this mood. Alfred Roth (1879-1948), a leading functionary in the antisemitic German National Clerks Association, and the veteran antisemite Theodor Fritsch (1852-1933) sent an “exposé” to the Kaiser, other German princes, and leading figures to warn them that the Jews had become “the rulers of economic life in Germany”. This legend, invented and circulated by the right, was similarly evident in Austria. In the Habsburg Monarchy as well, the vanishing hope of victory and the worsening supply situation in 1915 fostered the growth of antisemitic opinion in the rightwing extremist and völkisch organizations and in the Reichpost, the official organ of the Christian Social Party. The main target of antisemitic propaganda in Austria was the mostly impoverished Jewish refugees from Galicia, who, fearing pogroms and the attack of the Russian army, had fled to Vienna in great numbers. While the first arrivals in 1914 were greeted with a certain sympathy, they later were blamed for the worsening social problems and high level of criminality. Antisemites claimed that “Eastern Jews” were war profiteers and lived in the best districts, while the “Aryans” were unable to find a place to live. The accusations were so extensive that by the end of the war terms like “‘Eastern Jew’, ‘Galician’, ‘profiteer’, ‘hoarder’, ‘speculator’, and ‘usurer’ had become practically synonymous”.[7]

As the war became protracted and the population faced increasing austerity, tensions rose and antisemitism returned to public debate in 1916 in Bohemia and Moravia as well as in Hungary. Hungarian banks owned by Jews were accused by antisemites, like Károly Huszár (1882-1941) of the antisemitic Catholic People’s Party, to have been behind many dubious transactions. “Some papers and periodicals quickly took up the issue”.[8] In the Hungarian parliament, controversial and fierce debates on the “Jewish question” took place. In the Russian Empire, the military introduced economic measures severely restricting trade. This led to a food crisis and galloping inflation in 1916-1917, which reinforced negative attitudes towards Jews.

Despite its Triple Alliance with Germany and Austrian-Hungary, Italy had entered the war on the Allied side in May 1915 and the country’s Jewish population displayed great patriotic fervor, although it had been just as split between intervention and neutrality as the rest of the Italian population. Expressions of antisemitism remained a marginal phenomenon in Italy during the war, much in line with the weak presence of antisemitic agitators, the more so as a disproportionately large number of Jews ranked high in the Italian army.

Despite its prior close foreign policy ties to Germany and the Habsburg Monarchy, Romania remained neutral in 1914. In August 1916 Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente, not least enticed by the proposal that Transylvania and the Bukovina would be ceded to Romania should the Allied powers prove victorious. By the end of the year however, the Central Powers had succeeded in occupying about half of Romania, including Bucharest. Meanwhile in Iaşi, the “capital” of Romanian antisemitism, the government managed to mobilize the population, not least by promising agrarian reforms, while Jews and other “aliens” were treated as second-class citizens and soldiers.

In Russia antisemitism intensified alarmingly. In January 1915, a circular ordering the forced expulsion of Jews and other suspicious persons from the entire region of military activity was implemented, a measure only suspended in 1917. Confronted with Russia’s military plight and enormous economic problems, the right saw a conspiracy by Jews and Freemasons, moving them to intensify their antisemitic agitation. Despite serving in the army, Jews were stamped as speculators and suspected of spying for the Central Powers.

These claims did not go unchallenged. Leading Russian intellectuals published An Appeal for the Jews in which they denunciated “the evil effect of the governmental discrimination against Jews”.[9] This protest ultimately had as little impact as those made by Russia’s Western allies in response to antisemitic violence. From May through to October 1915, as the Russian troops were forced into a hasty retreat (the “Great Retreat”) and a “scorched earth” policy was launched, “evacuations” became increasingly chaotic and brutal. Those forced to move often had to so without notice. These expulsions were accompanied by a wave of around one hundred pogroms, almost entirely initiated by Cossacks hostile to Jews, primarily interested in appropriating Jewish possessions and property. The respective local populations frequently joined the plundering. In the conquered areas like Galicia and the Bukovina, hostages were taken as a means to secure the loyalty of the Jews. At the same time, however, restrictions prohibiting Jews living outside the Pale of Settlement were lifted and the government allowed Jews to attend secondary schools and universities. Both of these measures were exploited for war propaganda, aiming to refute the accusation of antisemitism made by the Western powers.

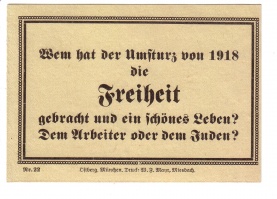

Antisemitism in the countries of the Central Powers became further radicalized when the United States entered the war in April 1917, a country antisemites condemned as materialistic and vilified as being dominated by Jews.[10] A merger movement sprang up, with German antisemites and rightwing nationalists joining forces. They intensified their attacks on the politics of the domestic “truce” and destabilized domestic politics to such an extent that the government succumbed to their pressure. As a result, two antagonistic political camps formed in Germany. On one side, there was the Conservative Party and sections of the National Liberals, backed by many of the leading associations representing industry and agriculture and the Pan-German League. They were only willing to accept a “victorious peace” that secured the German Reich a dominant position in Eastern Central Europe and fulfilled its aspirations to be a world power. Domestically, they demanded the “removal of the poison from the ethnic German body”, which meant primarily eliminating the perceived influence of Jews and the establishment of an authoritarian state.

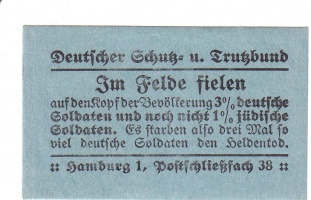

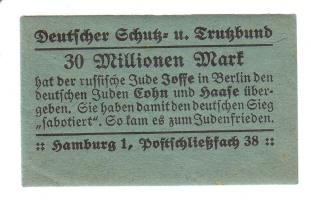

Encompassing liberals, socialists, Jews, and Catholics, the opposite camp sought a negotiated peace without annexations, while domestically they advocated democratizing the political system and promised social reforms. In the summer of 1917, the Reichstag passed a Peace Resolution (the July Resolution) – albeit ultimately ignored by the German military and the Allies – with the votes of the Social Democrats, the Center, and the Progressive People’s Party. In response, the Pan-German League, the Association of Farmers, veteran organizations, and a host of antisemitic groups launched an acrimonious campaign, denouncing the sought-after negotiated peace as a “Jewish peace”. A coalition movement unifying the German Right emerged, leading to the founding of the German Fatherland Party in September 1917, which served as a kind of umbrella organization for numerous völkisch-nationalistic circles, among them also antisemitic activists and groups. Just a year later it was estimated to have 800,000 members.[11]

Along with the conflict over a “victorious” or “negotiated” peace, the debate about the “Eastern Jews”, i.e. the immigration of Jews from Tsarist Russia (around 90,000 persons up to 1915), already ignited prior to the war, once more came to prominence. In 1915 the Pan-German Georg Fritz (1865-1944) published the brochure Die Ostjudenfrage. Zionismus und Grenzschluß in which, given Germany’s eastward expansion, he warned in the most drastic terms against the mass immigration of “millions of people who are not only poor, physically and morally deformed, but are racial aliens, Jewized Mongolians”.[12] This sort of propaganda ultimately found success. In April 1918, the German Reich closed its borders to Jews from Eastern Europe until the end of the war, citing the danger of epidemics such as typhus. This negative view of Eastern European Jews was underpinned by the experiences of German soldiers with “liberated Eastern Jews”: on the one hand, there was a sense of pity for these Jews and their plight; on the other hand, however, there was also a sense of revulsion and disconcertment at the strange “Eastern Jewish world”.[13]

As the war entered its final phase, the antisemitism of rightwing extremist groups came increasingly to the fore, in particular in the Pan-German League. Already in 1917, the Pan-Germans had declared the war to be a battle of survival between “Germanness” and “Judaism”, and in September 1918 they founded a “Committee for Combating Judaism”. This committee ruthlessly employed antisemitism as an instrument of political struggle, stating that the “all-pervading Jewish influence” was the cause of Germany’s impending collapse. They claimed that defeatism on the home front, allegedly instigated and stirred on by Socialists and Jews, had caused the defeat of the army, which had been “unvanquished in the field”. After Germany’s defeat, the Pan-German League together with other rightwing groups spread this “stab-in-the-back” legend.

In Austria, antisemitism also intensified after the United States entered the war. With a relaxation of censorship, attacks against Jews in the press increased.[14] The antisemitic press accused Jewish immigrants in the United States and Britain of agitating against their onetime homeland. Amongst the population and in parliament claims were rife that the Galician Jews were Russian spies and sought to evade military service. Although investigations failed to find evidence substantiating such claims, antisemites persisted in their allegations, even after the war had come to an end. In comparison to Germany, however, there were fewer instances of harassment against Jews in the Austrian army.

Following the death of Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916), the Reichsrat (Imperial Council), suspended for the preceding three years, was reconvened under Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922), in May 1917. With society gripped by crisis and the various nationalities in conflict, the council was an ideal political arena for the German-Austrian parties to express their anti-Jewish agitation. In the summer of 1917, “the German-Austrian parties in the Reichsrat made antisemitism their main program”.[15] At council sessions Jewish and Social Democrat deputies criticized antisemitic incidents in the army, while the Christian Socialists complained that few Jews were to be found in the trenches. From March 1918, the number of antisemitic articles in Viennese newspapers increased markedly.[16] In the spring and summer of 1918 assaults targeting Jews grew into mass demonstrations, which, enjoying the tacit approval of the authorities, turned increasingly violent. One example of this escalation was the massive assaults launched on “German National Day” in June, as Christian Socialists and Pan-Germans took to the streets in Vienna to display their loyalty to Emperor Charles. Along with the ongoing shortages, the pogrom-like atmosphere stemmed from the failure of the final large-scale Austrian-Hungarian offensive on the Italian Front in June 1918. Anti-Jewish agitation also intensified in Hungary during the war years. Social conflicts and issues were increasingly considered and interpreted through an antisemitic prism. Hence, antisemitism became a crucial building block when the political landscape was reshaped.

In the Russian Empire, the situation for Jews took a different turn towards the end of the war, as the revolution granted them legal equality. On 20 March 1917, the provisional government under Aleksandr Kerensky (1881-1970) lifted all restrictions. The right responded with the rumor that Kerensky was of Jewish descent. In this phase when the state and its institutions were collapsing, between April and September 1917, no less than 3,500 anti-Jewish pogroms took place, the atmosphere further aggravated by violence against Finns, Ukrainians, and Armenians. Antisemitism was not overcome even with the establishment of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution, not least because the anti-Soviet groups exploited the comparatively high portion of Jewish functionaries amongst the Bolsheviks in their propaganda. Because ethno-religious conflicts ran contrary to communist ideology, the Council of People’s Commissars decided to publish an article in Izvestia on 27 July (9 August) 1918 that criticized how counter revolutionary forces were using antisemitic agitation in the pogroms, arguing that national animosities only served to adversely overshadow the genuine interests of workers and farmers and weaken the ranks of the revolutionaries. Vladimir Il’ich Lenin (1870-1924) considered the issue to be so important that he delivered a radio speech against antisemitism in March 1919 which was later rebroadcast several times.[17] Nevertheless, this period of revolutions and civil war meant ongoing pogroms and persecution for many Jews.

In Romania as well, where the army had intensified its measures against “aliens” at the outbreak of the war and, suspecting Jews of acting as spies and collaborating with the Germans, had expelled them from all areas in the vicinity of the front, the government now changed course, offering the Jewish population the prospect of civil and political equality in 1917. That the issue was placed on the political agenda in the middle of the war testifies to the importance all sides had attached to the so-called “Romanian Jewish question.” In 1917 Ferdinand I, King of Romania (1865-1927) thus promised land and political rights to the farmers in April 1917, and then in May, after the February Revolution and the emancipation of Russian Jews, also signaled his willingness to make concessions to the Jewish population. This was played out against two broader considerations: firstly, the vehement protest of Russia against the unequal treatment of Romanian Jews, and secondly political pressure from the Western Allies, which were concerned about Romania’s image in the world; its poor reputation was undermining their own credibility as nations fighting for civilization and democracy. Because Romania was reliant on the goodwill of its alliance partners to achieve its territorial aims, the emancipation of the Jewish population was put to parliament for debate, although implementing specific measures was to be delayed until after the war.

In the wake of the October Revolution and Russia’s exit from the war, Romania was forced to conclude a separate peace with the Central Powers. Under the pressure exerted in negotiations for the Treaty of Bucharest signed in May 1918, the emancipation of Romanian Jews once again was placed on the agenda and ultimately laid out in Article 28 of the Treaty under the terms for religious equality. The Central Powers were hoping to land an image coup, while for the Romanian government the “Jewish question” was closely connected to Romanian expansion plans. The emancipation of the Jews was an issue all sides exploited for their own purposes, motivated by domestic and foreign policy considerations as well as the strategic rationale of alliance politics. In the treaties signed in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, the Allies linked Romania’s territorial gains to the Jews and other national minorities receiving civic rights, which were, however, first awarded with Romania’s constitutional amendment of 1923, for the plans to grant collective equality to the Jews, perceived as a humiliation for Romania, met with strong resistance.

From 1917 the wave of antisemitism also reached those countries where antisemitic propaganda had previously found little resonance. In Britain for example, Jews were confronted with – as the war entered a particularly dramatic phase – the allegation that they secretly were sympathetic to the German cause. British antisemitism was closely tied to Germanophobia. At this time, the negative image of German Jews as corrupt and evil circulated in the British public, and imagery expressing this view was to be found in stories, newspaper reports, pamphlets, and essays. The British journalist Leopold James Maxse (1864-1932) was just one of many conservative authors who accused the government of sacrificing the fate of the nation by following the plans of the German or international Jewry. Following the October Revolution in Russia, Britain’s established political class feared the spread of a Bolshevist world revolution, with radical Russian Jews seen as playing a leading role. Adding to the edgy mood were restrictions necessitated by the war, which in cities like London and Leeds triggered outbreaks of violence against Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, who were accused of evading military service. Once the war was over however, the intensity and scale of anti-Jewish resentment quickly receded.

The Radicalization of Antisemitism in the Early Postwar Years↑

While antisemitism before and after the war reveals a number of continuities, particularly in terms of the organizational structures of its groups, the persons involved, and the “causes” of its complaints, there is nevertheless much evidence to support the claim that the collapse of the European order of 1914 and the first ever mass-scale war with its ensuing mass death represents a caesura. The experience of the “great seminal catastrophe” of the twentieth century led to the spread of a revolutionary hyper-nationalism, of course most – but not solely – prevalent in the vanquished states, where defeat and revolution had also left an indelible mark, strengthening the willingness of the population to believe the “old” assertion propagated by antisemites, that “solving the Jewish question” equated to solving all social and ethno-national problems. Even if the roots of German and Austrian antisemitism are to be found in the period before 1914, the immense dynamism and radicalness evident after 1918 can only be explained through the impact of the war, defeat, revolution, and counterrevolution.

On the other hand, the end of the war and the first postwar years also opened promising political prospects. Defeat was followed by democratic revolutions, while new republics emerged out of the ruins of the Habsburg Monarchy and the Tsarist Empire. Both of these events gave Jews in Central Europe new hope of improving their legal and political situation; internally however, this hope was cause for conflicts between Jews. A large number of them were actively involved in the soviet council movements in the early revolutionary phase and would become committed members of the Bolshevist and Communist parties in the coming years. This alarmed middle-class Jews. Not without good reason, they feared that antisemitism would intensify as a result of revolution. This is indeed what happened: precisely at this historical juncture, antisemites coined new catchphrases like “Jewish Bolsheviks” and the “Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy”, both of which would go on to have a far-reaching impact on the further development of antisemitism. These catchphrases surfaced immediately after the Bolshevist insurrection in Petrograd and, spreading rapidly, entered the political vocabulary of all European countries.

In the context of the political upheavals after the war, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, translated into a number of European languages, became one of the most influential pamphlets of extreme antisemitism in Europe and the USA. In 1921 a translation was even published in Italy, a country where antisemitic attitudes and violence against Jews had failed to take hold, sparing it the otherwise prevalent radicalization of antisemitism during the war, as well as in Great Britain, where the “war experience and the Bolshevik revolution served as momentous foils for eager reception of these ‘protocols’”.[18]

Although extreme antisemitism had begun to crystallize during the First World War and this process was forced along by the ensuing revolutions, the decisive impetus towards further radicalization came with the subsequent counterrevolutionary movements. Germany and Hungary were at its epicenter. The development of antisemitism in Eastern Central Europe was ultimately shaped by the fact that the conflict on the Eastern Front did not end in 1918 but passed directly into the Polish-Soviet War that would last until 1921 and in which similarly horrific acts of extreme antisemitic violence took place as in counterrevolutionary Hungary. In autonomous and independent Poland, antisemitic violence did not let up with the end of the Polish-Soviet War. It was, rather, part of the difficult constitution phase of the new Polish republic and was manifest in both everyday discrimination as well as in anti-Jewish pogroms perpetrated by the military and police in the various Polish border wars from 1918 to 1920 (in Lviv, Lida, Pinsk, and Vilnius) and the extremely volatile election campaign, marked by unrest and political clashes, to decide the first presidential election of the Polish Republic. A week of antisemitic violence in December 1922 culminated in the assassination of the newly elected president, Gabriel Narutowicz (1865-1922).

Similarly dramatic and violent was the development during the civil war in Russia and the Ukraine, where tens of thousands of Jews were the victims of 1,200 pogroms, carried out primarily by the counterrevolutionary White Army and local warlords between December 1918 and April 1921, even if these acts of extreme violence were often not motivated by antisemitism and Jews were not the sole victims. The situation remained calm only in Lithuania. Here the constitution of the new state led to political and civic equality and the social integration of the Jews, who were also granted extensive autonomy rights.

After 1918, aggressive nationalism was rampant in the states emerging out of the ruins of the Habsburg and Tsarist Empires. Expressed in “national struggles,” it was not solely directed against the Jewish minority. Hatred of Jews was often combined with a fierce rejection of the nationalities dominant prior to the First World War, with the Jewish population considered to be their allies: thus, Slovakian antisemitism was also anti-Hungarian, Ukrainian anti-Polish, and Polish antisemitism both anti-German and anti-Russian. In Prague, anti-German riots in December 1918 led to attacks against Jews while in late fall of 1918, the Slovakian population in upper Hungary violently assaulted and looted Jewish merchants, property owners, and innkeepers, with such incidents also occurring in many places in the rest of Hungary. In the Habsburg Crownland Croatia-Slavonia, “where antisemitism until 1918 was usually expressed in writing or orally”, the generally desperate situation in the country at the end of the war also “resulted in the escalation of antisemitic outbursts, which sometimes resulted in physical attacks on Jews.”[19]

The dismantling of the multiethnic Habsburg Empire meant that the new Austrian Republic occupied a mere fifth of the former state territory in which Jews were now the “solitary scapegoats”[20] and they were accordingly blamed for the “national humiliation”, the political instability, and economic crisis of the postwar years. As in Germany, Jews were vilified as conniving profiteers of war and inflation, leading to the accusation that they had undermined the war effort on the home front and thus bore responsibility for the defeat of the Central Powers. In its manifesto published on 24 December 1918, the Christian Social Party called on the “German-Austrian people to take decisive defensive action against the Jewish menace”. Similar to the situation in Germany, the presence of Eastern European Jewish refugees was the main issue targeted by antisemitic agitation in the postwar years. Both the Christian Social and German National Party exploited this issue extensively in the election campaign for the first National Assembly in February 1919, denouncing the Social Democrats as the “Jew protection force”.

What raised the ire of antisemites above all was the prominent economic and cultural position of Viennese Jews. For the Catholic clergy and the Austrian population, “Red Vienna”, governed by reform-oriented but thoroughly orthodox Marxist Social Democrats, with many Jews amongst their ranks, was tainted by “typically Jewish” characteristics: materialism, parasitism, and revolution. Similar to the situation in Germany and Hungary, Jews in Austria were identified with modernization and Bolshevism. In their anti-Jewish agitation, the Christian Socialists openly incited violence and antisemitic riots took place in Vienna, targeting “Eastern Jews” in the main. The postwar wave of antisemitism with its large mass demonstrations continued into 1923 before abating somewhat. In France, which witnessed a large wave of immigration by Eastern European Jews in the immediate aftermath of the war, the new arrivals were also confronted with an increasingly hostile environment which impeded their integration.

From 1914 to 1920, Hungary experienced several fundamental upheavals in quick succession which intensified after the collapse of the monarchy. Having lost the war, under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon signed in 1920, the country was forced to cede a large part of its territory, giving rise to national chauvinism and territorial revisionism. Frequent system changes led to an evaporation of state power and sparked waves of antisemitic violence all over Hungary, which had already began in late 1918. The main actors in these riots were soldiers who had returned from the front in great numbers, sections of the impoverished urban poor and deprived peasants, who started looting Jewish homes and shops, attacking and beating up thousands of Jews. The first revolution of October 1918, the “Aster Revolution”, was soon followed in March 1919 by the Bolshevist Revolution under Béla Kun (1886-1938) which founded the Hungarian Soviet Republic. With Jews disproportionately represented in the leadership, Hungary was seen as being under the yoke of “Jewish rule”. Jews were accused collectively of having betrayed the Hungarian national cause and operating as the “vanguard” of Soviet Russia, even though scores of Jews were amongst the civilian victims of thuggish communist enforcers.

The struggle against this regime was accompanied by mass demonstrations and pogroms in 1919-1920 (more than half of the 5,000 victims were Jews), committed as part of the “White Terror” mainly by the “National Army” under the command of Miklós Horthy (1868-1957), later to serve as Regent, paramilitary units, and riot police battalions comprising radical antisemitic students. Sections of the general population also took part. Tolerated by the ruling elite as a just punishment, this violence marked a turning point in the relationship between Hungarians and Jews. The antisemitic mood in society intensified over the course of these upheavals, with Hungarian antisemites increasing their political activity. Numerous so-called “patriotic” associations were founded, with antisemitism at the very heart of their worldview, such as the Közszoglgálati Alkalmazittak Nemzeit Szövetsége (National Alliance of State Officials) and extreme nationalist student fraternities, which actively terrorized Jewish students in Hungary’s universities. It was primarily the middle classes, established as a third political force alongside landowners and the upper classes, who rejected equality for Jews. From 1919, antisemitism became an element of a nationalist-Christian politics that until the mid-1920s prohibited the re-founding of Jewish organizations and associations suspended during the war and, in 1920, enacted the first antisemitic law in Europe, imposing a numerus clausus on the number of Jews – corresponding to their share of the overall population – able to attend university. This law paved the way for a governmental antisemitism in Hungary, with similar numerus clausus laws also passed in Poland and Romania.

Conclusion↑

The First World War marked a fundamental caesura not only for European history generally, but also for Jewish history as the conflict triggered a new phase of European antisemitism. Mainly in the Central Powers, but also in some of the newly established nation states in Eastern Central Europe, experiences during the war led to a profound radicalization of animosity towards Jews and the emergence of new motifs in antisemitic language.

At the outbreak of the war it initially seemed that the old hostility towards Jews could be overcome in large parts of Europe, while for their part, Jews hoped to finally complete their integration into society by fulfilling what they saw as their patriotic duty. As confidence in a quick victory dwindled and it soon became apparent that this had been an illusion, as the experiences at the front became all the more traumatic, and society in general increasingly brutalized under the influence of the war, public opinion shifted dramatically in Germany and the Habsburg Monarchy. Antisemitism also visibly intensified in the Entente countries. Looking for a scapegoat for the unsuccessful and protracted war, antisemites accused Jews of being responsible for military setbacks and defeats, although more than a million Jews served in the various European armies. Antisemitism was not limited to provocative acts of agitation and malicious claims, but found a direct outlet in violent attacks on Jews, their organizations, and property. Immediately after the war, contemporaries may well have expected that peace would usher in a new phase of democratization in Europe, one that would bring with it full emancipation for Jews in all European countries. But the revolutions which broke out in the onetime Central Powers and Russia had a profound impact on the middle classes, instilling them with a deep-seated sense of insecurity; moreover, counterrevolutionary movements aggravated the already poisonous and violent social climate even further, contributing decisively to the formation of a new, more extreme antisemitism.

From 1879 to 1914, the years of its rise as a social and political movement, antisemitism was a Europe-wide phenomenon. Its radicalization as a consequence of the Great War as well as of the following revolutions and counterrevolutions, was also a European process, albeit less uniform. After a considerable similar decrease at the outbreak of the war, antisemitic agitation grew stronger during the war primarily in the countries of the Central Powers. Antisemitic campaigns were directed at Jewish immigration and they radicalized charges of shirking and war profiteering.

After the war, the new motif of Jewish Bolshevism emerged in antisemitic campaigns all over Europe, while the Protocols of the Elders of Zion gained acceptance, even in countries where antisemitism had met with only weak response such as Italy and Great Britain. The process of radicalization was particularly strong in the countries that had lost the war, but it also occurred in Poland and remained strong in Romania, which both belonged to the winning side. Numerus clausus laws not only passed in Hungary, but also in Poland and Romania. The language of antisemitism did not differ much according to national peculiarities, but became more radical according to the specific political and economic problems in establishing the new political order.

Werner Bergmann and Ulrich Wyrwa, Technische Universität Berlin

Section Editors: Holger Afflerbach; Roger Chickering

Notes

- ↑ Volkov, Shulamit: Antisemitism as a Cultural Code: Reflections on the History and Historiography of Antisemitism in Imperial Germany, in: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 23 (1978), pp. 25-4.

- ↑ Benbassa, Esther: Histoire des Juifs de France. Paris 2000, p. 221.

- ↑ Strauss, Herbert A.: Great Britain – The Minor Key, in: Strauss, Herbert A.: Hostages of Modernization. Studies in Modern Antisemitism 1870-1933/39: Germany – Great Britain – France, Vol. 3/1, Berlin, New York 1993, pp.289-293, p. 291.

- ↑ Lohr, Eric: The Russian Army and the Jews: Mass Deportation, Hostages, and Violence during World War I, in: The Russian Review 60 (July 2001), pp.404-419, p. 405.

- ↑ Mentzel, Walter: Weltkriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien 1914-1918. In: Heiss, Gernot & Rathkolb, Oliver (eds.): Asylland wider Willen: Flüchtlinge in Österreich im europäischen Kontext seit 1914, Wien 1995, pp. 17-44; Hoffmann-Holter, Beatrix: Abreisendmachung: Jüdische Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien 1914 bis 1923, Vienna 1995.

- ↑ Zechlin, Egmont: Die deutsche Politik und die Juden im Ersten Weltkrieg. Göttingen 1969, p.516.

- ↑ Pauley, Bruce: From Prejudice to Persecution. A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism, Chapel Hill et al. 2000, p. 69f.

- ↑ Bihari, Péter: Aspects of Anti-Semitism in Hungary 1915-1918. In: Ernst, Petra / Grossman, Jeffrey/Wyrwa, Ulrich (eds.): Quest The Great War. Reflections, Experiences and Memories of German and Habsburg Jews (1914-1918), Issues in Contemporary Jewish History 9 (October 2016), pp. 62f. Online: www.quest-cdecjournal.it/focus.php?id=377.

- ↑ Baron, Salo W.: Jews in Russia: The First World War and the Revolutionary Period, in: Strauss, Herbert A. (ed.): Hostages of Modernization. Studies in Modern Antisemitism 1870-1933/39: Austria - Hungary - Poland - Russia, Vol. 3/2, Berlin, New York 1993, pp. 1291-1311, p.1300.

- ↑ Sombart, Werner: Die Juden und das Wirtschaftsleben. Leipzig 1911, pp. 31, 38-48. These remarks had widely been quoted by obsessive antisemites like Theodor Fritsch: Handbuch der Judenfrage, 28. Aufl. Leipzig 1919, pp. 259-262; see also: Schwabe, Klaus: Anti-Amerikanism within the German Right 1917-1933. In: Jahrbuch für Amerikastudien 21 (1976), S. 89-107.

- ↑ Hagenlücke, Heinz: Deutsche Vaterlandspartei. Die nationale Rechte am Ende des Kaiserreiches, Düsseldorf 1997. For Hagenlücke, the DVLP was not a “philosemitic organization”, but he stresses that Jews could become party members and the leading group did not use antisemitism as a political tool.

- ↑ Fritz, Georg: Die Ostenjudenfrage. Zionismus und Grenzschluß, Munich 1915, p. 43.

- ↑ Aschheim, Steven E.: Brothers and Strangers. The East European Jews in German and German Jewish Consciousness, 1800-1923, Madison 1982.

- ↑ Lamprecht, Gerald: Juden in Zentraleuropa und die Transformation des Antisemitismus im und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. In: Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 24 (2015), pp. 63-88, p.82.

- ↑ Pauley, From Prejudice to Persecution 2000, p.71.

- ↑ Pauley, From Prejudice to Persecution 2000, p.70.

- ↑ Herbeck, Ulrich: Das Feindbild vom “jüdischen Bolschewiken”: Zur Geschichte des russischen Antisemitismus vor und während der Russischen Revolution, Berlin 2009, p. 326.

- ↑ Lebzelter, Gerda: Political Anti-Semitism in England 1918-1939. London 1978, p. 14.

- ↑ Hameršak, Filip & Dobrovšak, Ljiljana: Croatian-Slavonian Jews in the First World War. In: Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History 9 (October 2016), p.117.

- ↑ Berkley, George E.: Vienna and its Jews. The Tragedy of Success 1880s-1980s, Cambridge, Mass. 1988, p.149.

Selected Bibliography

- Angress, Werner T.: The German army's 'Judenzählung' of 1916. Genesis-consequences-significance, in: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 23, 1978, pp. 117-137.

- Bergmann, Werner / Wetzel, Juliane: Antisemitismus im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg. Ein Forschungsüberblick, in: Thoß, Bruno / Volkmann, Hans-Erich (eds.): Erster Weltkrieg, Zweiter Weltkrieg. Ein Vergleich. Krieg, Kriegserlebnis, Kriegserfahrung in Deutschland, Paderborn 2002: F. Schöningh, pp. 437-469.

- Berkley, George E.: Vienna and its Jews. The tragedy of success, 1880s-1980s, Cambridge; Lanham 1988: Abt Books; Madison Books.

- Bihari, Péter: Lövészárkok a hátországban. Középosztály, zsidókérdés, antiszemitizmus az első világháború Magyarországán (Trenches in the hinterland. Middle class, Jewish question, antisemitism in Hungary during World War I), Budapest 2008: Napvilág.

- Budnitskii, Оleg V.: Rossiiskie evrei mezhdu krasnymi i belymi, 1917-1920 (Russian Jews between the Reds and the Whites, 1917-1920), Мoscow 2006: Rosspėn.

- Budnitskii, Oleg V.: Russian Jews between the Reds and the Whites, 1917-1920, Philadelphia 2012: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ernst, Petra / Grossman, Jeffrey / Wyrwa, Ulrich (eds.): The Great War. Reflections, experiences and memories of German and Habsburg Jews (1914-1918), in: Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History. Journal of Fondazione CDEC 9, 2016

- Fine, David J.: Jewish integration in the German army in the First World War, Boston 2012: De Gruyter.

- Fischer, Rolf: Entwicklungsstufen des Antisemitismus in Ungarn 1867-1939. Die Zerstörung der magyarisch-jüdischen Symbiose, Munich 1988: R. Oldenbourg.

- Iancu, Carol: Evreii din România (1866-1919). De la excludere la emancipare (The Jews in Romania (1866-1919). From exclusion to emancipation), Bucharest 2009: Hasefer.

- Iancu, Carol: Les Juifs en Roumanie, 1866-1919. De l'exclusion à l'émancipation, Aix-en-Provence 1978: Éditions de l'Université de Provence.

- Jochmann, Werner: Die Ausbreitung des Antisemitismus in Deutschland 1914-1923, in: Mosse, Werner E. / Paucker, Arnold (eds.): Deutsches Judentum in Krieg und Revolution 1916-1923. Ein Sammelband, Tübingen 1971: J. C. B. Mohr, pp. 409-510.

- Mosse, Werner E. / Paucker, Arnold (eds.): Deutsches Judentum in Krieg und Revolution 1916-1923. Ein Sammelband, Tübingen 1971: J. C. B. Mohr.

- Pauley, Bruce F.: From prejudice to persecution. A history of Austrian anti-semitism, Chapel Hill 2000: University of North Carolina Press.

- Polonsky, Anthony / Riff, Michael: Poles, Czechoslovaks and the 'Jewish question‘, 1914-1921. A comparative study, in: Berghahn, Volker R. / Kitchen, Martin (eds.): Germany in the age of total war, London; Totowa 1981: Croom Helm; Barnes & Noble, pp. 63-101.

- Pulzer, Peter: Der Erste Weltkrieg, in: Lowenstein, Steven M. / Mendes-Flohr, Paul; Pulzer, Peter et al. (eds.): Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit. Umstrittene Integration 1871-1918, volume 3, Munich 1997: Beck, pp. 356-380.

- Reder, Eva: Im Schatten des polnischen Staates. Pogrome 1918-1920 und 1945/46 - Auslöser, Bezugspunkte, Verlauf, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 60/4, 2011, pp. 571-606.

- Rosenthal, Jacob: 'Die Ehre des jüdischen Soldaten'. Die Judenzählung im Ersten Weltkrieg und ihre Folgen, Frankfurt a. M. 2007: Campus.

- Schuster, Frank M.: Zwischen allen Fronten. Osteuropäische Juden während des Ersten Weltkrieges (1914-1919), Cologne 2004: Böhlau.

- Sieg, Ulrich: Jüdische Intellektuelle im Ersten Weltkrieg. Kriegserfahrungen, weltanschauliche Debatten und kulturelle Neuentwürfe, Berlin 2001: Akademie Verlag.

- Strauss, Herbert Arthur (ed.): Hostages of modernization. Studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39. Austria - Hungary - Poland - Russia, Current research on antisemitism, volume 2, Berlin; New York 1993: W. de Gruyter, online: http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3042097 (Retrieved 2017-01-10 10:05:38).

- Strauss, Herbert Arthur (ed.): Hostages of modernization. Studies on modern antisemitism 1870-1933/39. Germany - Great Britain - France, Current research on antisemitism, volume 1, Berlin 1993: De Gruyter.

- Szabó, Miloslav: 'Von Worten zu Taten'. Die slowakische Nationalbewegung und der Antisemitismus, 1875-1922, Berlin 2014: Metropol.

- Zechlin, Egmont: Die deutsche Politik und die Juden im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 1969: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.