Introduction↑

The comprehensive revision that historical research into the Great War has undergone in the last few years has brought new narrative spaces relating to the wartime experience to the forefront. In the case of Spain, the country’s neutrality is one of these. It has received renewed attention not only as a specific foreign policy, but also as a social and intellectual stance on the contentious issue of the world at war. Generally speaking, this phenomenon involved a social coding of the hostilities that had a strong impact on nationalist processes unfolding the length and breadth of Spain. For many Spaniards, the armed conflict would not only be fought on distant fronts, but would also unexpectedly intrude on their daily lives.

War “Breaks Out” in Neutral Spain↑

The devastating humanitarian effects of the Great War generated vivid images of its absurdity in the “mental maps” of Spaniards, who – like many citizens of other neutral countries – were also its collateral victims. During the first weeks of the conflict, Spanish workers and miners employed in Germany, Belgium, or France were already being forced to return home by the advancing German army. The land border of the Basque Country and port cities such as Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca witnessed this migratory flow. Although no accurate figures exist, it is estimated that more than 10,000 Spaniards started on the long road home, fleeing from the horrors of war. Later on, French, British, German and Italian residents in Spain would also return to their home countries, mostly to go to the battlefronts.

War Reporting↑

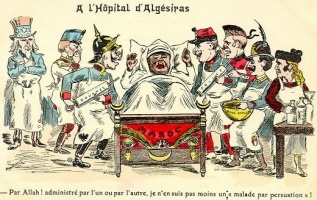

War chronicles were given their own space in Spanish newspapers, with monographic sections devoted to the progress of military operations and accountability in relation to the conflict. Special coverage was also given to news concerning the rest of the neutral countries, particularly the preventive measures taken by them against possible aggressions by the belligerent powers. In this respect, the Great War favoured the modernization of Spanish journalism, whose structure in 1914 was still more anchored in the 19th century partisan press model than in New Journalism. On the whole, and notwithstanding certain discontinuities in editorial policy, the press that acted as a mouthpiece for liberals and radicals took a pro-Allied stance (e.g. El Liberal, El Socialista, El Heraldo de Madrid, El Sol, El Diario Universal, etc.), while the sympathies of those newspapers, which represented the interests of conservatism and the Church lay with Germany and the Central Powers (ABC, Nueva España, El Correo Español, El Debate, etc.).

The Spanish war correspondents, influenced by their sympathies for one camp or the other, played an important role in keeping their compatriots informed about the conflict. At times, news published in the same newspaper contained different viewpoints. This was the case with the Germanophile ABC. While correspondents such as Antonio Azpeitia (1891-1939), pseudonym of Javier Bueno y García, and Juan Pujol (1883-1967) toed its editorial line, the daily also published the pro-Allied chronicles of Azorín (1873-1967), pseudonym of José Martínez Ruiz, and Alberto Insúa (1883-1963), pseudonym of Alberto Galt y Escobar. However, it was particularly women such as Carmen de Burgos (1867-1932) and Sofía Casanova (1861-1958) who, influenced by the ideals of pacifism and the anti-war sentiment prevailing during the pre-war period, left accounts of the barbarity in all its magnitude. This position could be summarized in the slogan “War against War” that Carmen de Burgos had already employed during her time as correspondent in Morocco.[1] After fleeing from the war in Central Europe, she settled in London from where she would send her chronicles to the daily Heraldo de Madrid. For her part, Sofía Casanova worked for ABC covering news from the Russian front, which offered her the opportunity to follow the revolutionary events of 1917.[2]

Caught in the Middle↑

But the war did not stop at the Pyrenees or at sea, whether in the Atlantic or in the Mediterranean. It also had a direct impact on Spain. As the Italian vice-consul in Alicante Luigi Arduini went so far as to say, “Without being at war, the war was in Spain’s own backyard.”[3] Very similar views were expressed by the Spanish journalist Luis Bello (1872-1935), when he claimed that “it is the belligerent powers that strive to unbalance our neutrality and approach Spain because the country has not approached them.”[4] Spanish neutrality was challenged from the outset by the direct interference of the warring parties, violating on many occasions the country’s integrity and sovereignty. The control of the Iberian Peninsula – and especially its coast – was of vital importance for the secure trade and communications of France and Great Britain.

The economic war was also waged in Spain, due both to the circulation of English blacklists or vetoes of companies, newspapers, and Spanish citizens, and to the pressure of the war demand on the national market. That which the Allies called “business intelligence” was plainly seen by a sector of the Spanish press as blackmail. This is what a local newspaper had to say about the matter in 1916: “Move over to make room for me. What does the Government think about this? Is it that we Spaniards do not deserve a bit more respect from the Gentlemen Consuls of the Entente or is it that there is some truth in the adage, ‘give someone an inch and they take a mile’.” In May 1916, Juan Pujol reported in ABC that the national industry was manufacturing munitions of war for the Entente, clearly contravening its neutral status.

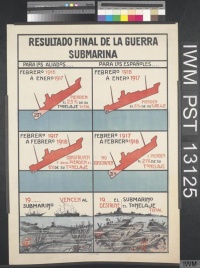

In 1917, the escalation of submarine attacks on shipping further highlighted the helplessness of Spain. Its national tonnage was one of the most affected by the German U-boat campaign, with estimates putting the loss at about sixty ships and 100 lives, despite disparity between figures. Since February of that year, civil governors had given instructions to editors-in-chief of newspapers to refrain from publishing naval news relating to the movement of ships or submarines in Spanish waters. Despite the mammoth efforts of the Spanish censors, it was impossible to avoid certain submarine-related news from being leaked to the public. On 11 June 1917, the German submarine UC-52, commanded by Ludwig Karl Sahl (1887-1973), sought refuge in the port of Cadiz, alleging mechanical problems, probably inflicted by the torpedoes of a British escort ship patrolling the Strait of Gibraltar. From March onwards, the UC-52 had sunk 18,213 tons of shipping. Despite the fact that the commander had given his word not to leave the Spanish port, on 29 June the U-boat set sail again. The same happened with the UB-49, commanded by Hans von Mellenthin (1887-1971), which, on 9 September of the same year, entered the military facilities of La Carraca shipyard in San Fernando. Moreover, the Diario de Cádiz associated the arrival of the U-boat with the sinking of the Spanish fishing steamboat Eva a few miles of Cape Spartel.

In the face of the intensity of the U-boat attacks in the area of the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, pamphlets and posters began to appear in Spanish ports stressing that the Central Powers had the right to legitimate defence, since while France and Great Britain were trafficking with Spanish wealth to their own benefit, Germans were dying of hunger due to the Allied blockade. One of the pamphlets that circulated in the port of Seville – one the country’s busiest ports, after those of Barcelona and Bilbao – in June 1917 is reproduced below:[5]

Those of you who live on a single wage and this you have to earn at sea, listen carefully to what I have to say and think twice before going to sea.

The Spaniard, from the moment he embarks on an English ship, is regarded as such; he loses all his rights and freedoms, he is no longer his own man, nor does he know where he is going or on what seas he will be sailing; […] if he embarks in a Spanish port, until he returns there, he does not only cease to be Spanish, but also a man, and becomes an automat […]

Now you know, dear colleagues: if you embark, even at the risk of being torpedoed, to earn a few pennies, you are in for the greatest disappointment of your life; so, do not embark on the ship of any belligerent or any Spanish ship whose course will take you through war zones.

Take note that Spanish ship owners who serve the belligerents laugh about the torpedoes, as they have nothing to lose, since they stay at home with a full wallet, but we run the risk of losing the only thing that nobody can return to us: LIFE.“Two Spains” at War↑

In addition to the direct effects of the economic and naval war in Spain, the Spaniards suffered from domestic shortages owing to the exorbitant rise in exports, together with a drastic reduction in imports. While in 1915 the inflation rate was 7.5 percent, by 1918 it had dangerously exceeded the 20 percent mark (a rate more in line with that of the belligerents). Speculative stockpiling became a very profitable business, given the inaction of the authorities. Minority sectors dedicated to the production and sale of basic goods and food products increased their profits massively. This was the case in the olive oil industry, the Catalan textile industry, the shipping business, and with the lead, iron, and magnesium mining concessions. Besides enriching a few, the war greatly reduced the purchasing power of the working classes, who, making the most of the weakness of the political system of the Restoration, mobilized against the regime. To this end, they resorted to revolutionary methods. As Lacomba wrote about the Spanish crisis of 1917, the war “rushed in and invaded the streets with its spies, smugglers, and gunmen” and “with the accompanying social and economic unrest, it began to shape a new scenario” in Spain.[6] To this was added the climate of internal conflict provoked by the loss of legitimacy of a system that systematically rigged elections.

In point of fact, the triple political, economic, and social crisis, which would lead in 1917 to the implosion of the Restoration system, “between war and revolution”, explains why, for so many years, Spanish and, in general, European historiography has focused on the domestic fracture as a kind of internal version of the war. After the fall of the Álvaro de Figueroa, Count of Romanones (1863-1950) in the spring of 1917, there were three different governments in under a year: Manuel García Prieto (1859-1938) from April to June; Eduardo Dato (1856-1921) from June to November; and García Prieto once again in December. The latter led a government of national unity, a forerunner of that which Antonio Maura (1853-1925) would preside over from March to November 1918. Even those in charge of the foreign propaganda services in Spain indicated that the internal division and resulting lack of social consensus on the war had more to do with domestic sympathies and phobias than with the international situation. Actually, the sense of public division between Maura’s supporters and opponents in 1909 was a clear precedent for social and political dichotomies throughout war. The stark rivalry between the “real Spain” and the “official Spain” would give rise to the well-known “civil war of words”. As Gerald Meaker and Romero Salvadó have suggested, the dialectical confrontation between these two blocs during the Great War would foreshadow the violent clash between the two “Spains” in the 1930s.[7] This idea, as Maximiliano Fuentes Codera notes, was shared by contemporary intellectuals such as Luis Araquistain (1886-1959), Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936), and Ramón Pérez de Ayala (1880-1962).[8] What follows is an attempt to make comparisons between the prevailing interpretation of the conflict, which draws on Spain’s internal situation, and the construction of the meaning of being neutral in a world at war, beyond domestic partisan infighting.

The Policy of a Neutral Ally: A National Dishonour?↑

The official decree of neutrality in August 1914 placed Spain in the realm of “deadly neutralities”, as was stated in the famous editorial piece published in El Diario Universal that same month and attributed to the liberal sector closest to the Count of Romanones. Thenceforth, two firmly established currents of opinion would divide members of both the establishment and outsiders to the left of the political spectrum. On the one hand, there were those who defended strict neutrality, a posture generally identified with the conservative world, and, on the other, there were those in liberal circles who were predominantly pro-Allies. But, besides partisan sympathies and phobias, the different governments formed between 1914 and 1918 persisted in what they believed to be the only policy open to them: neutrality sympathetic to the Entente. It was precisely the idea that “Spain was neutral because it had no other choice” that permeated the social and intellectual discourses of the pro-Allied and Germanophiles alike. The perceived weakness of the army, which had demonstrated its inability to defend Spanish interests against the insurgent tribes in Morocco, where over 80,000 men were deployed, was sufficiently widespread to lead to the emergence of a clear current of opinion in favour of belligerence. However, this only formed the basis of the arguments of both camps, since the conclusions varied greatly depending on the circumstances.

The Pro-Allied Position: Between Neutrality and War↑

Given the powerlessness of the Spanish government, the country’s neutrality began to be seen as a symbolic space of political action in which to articulate national regeneration discourses. This was particularly the case for pro-Allied intellectuals like Adolfo Posada (1860-1944), Azorín, Manuel Azaña (1880-1940), José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955), Unamuno, Araquistain, Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869-1968), Ramiro de Maeztu (1874-1936), and Ramón María del Valle Inclán (1866-1936). The aim was not to call for Spain’s participation in the war, but to whip up support for France and England in the cultural domain. It was an opportunistic conception of neutrality, which was also echoed in the workers’ press (editorial piece “Modos de ser neutral”, published in El Socialista on 12 September 1914).[9] In reality, it was hoped that the circumstances of war would force political change in Spain, due to the impossibility of seizing the initiative from within. This was the reason why certain pro-Allied persons took a jaundiced view of neutrality, a reflection of the “subaltern” identity that had been internalised following the loss of the country’s last remaining colonial possessions in America and the Pacific in 1898. In this vein, it is important to mention the stances taken by Araquistain and Melquiades Álvarez (1864-1936). Their political Anglophilia rested on the notion of the cultural and political superiority of Great Britain, which embodied a great Mediterranean power and counterweight to a France hostile to Spanish interests in Morocco. In fact, in some of their most controversial statements, they called for a sort of British tutelage of Spanish foreign affairs. Using España as a mouthpiece, Ortega y Gasset expressed his opposition to this stance. In this same magazine, whose first edition appeared in January 1915, Ortega claimed that Spain’s hopes of recuperating the role of Mediterranean power lay in mirroring Italy, a country – in his own words – that embodied the opposite of Spanish inertia.[10] In a way, the realization that a “Radiant May” was impossible in Spain explains why pro-Allied political circles would pay – thenceforth – greater heed to the community of neutral Latin American states.

But the position of the most influential pro-Allied sector as regards the war represented, to a great extent, a difficult conundrum limiting the struggle for the just cause to the domain of ideas. This view was also present in Spain’s participation in the League of Neutral Countries, which acted within the Allied sphere of influence and of which Unamuno and Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945) were delegates. For this reason, from 1917 the country’s official neutrality would become a hotly debated issue among these intellectuals. By then, the pro-Allied side had set the Anti-Germanophile League into motion. Moreover, Unamuno, together with Ramón María del Valle-Inclán and other writers, visited various war fronts. On 16 January of the same year, the poet Antonio Machado (1875-1939) wrote to Unamuno that neutrality consisted “in not wanting anything, not understanding anything.”[11] In that climate, hostile German propaganda actions and the sinking of the San Fulgencio would hasten the fall of the government of Romanones on 19 April 1917. In May, Araquistain wrote about “a drugged people” in the face of external aggression.[12] A few days later, about 25,000 people attended a pro-Allied meeting at the Madrid bullring.

However, not all of the pro-Allied resigned themselves to maintaining a passive attitude, with which they identified neutrality. Approximately 2,000 Spaniards enlisted in the ranks of the French Foreign Legion in order to fight on the front. Nonetheless, as David Martínez Fiol and Joan Esculies note, some of these Spanish volunteers assumed a Catalan identity so “that their struggle would be interpreted as a way of achieving the national liberation of Catalonia.”[13] In the autumn of 1914, El Progreso, a Barcelona-based Lerrouxist newspaper, published an article explaining how these volunteers had been enlisted. At the time, proponents of Alejandro Lerroux (1864-1949) collaborated in this task with the French consulate in the city. In 1915, Lerroux’s refusal to intervene actively led to the creation of new enlistment channels, such as those employed by the doctor Joan Solé i Pla (1874-1950) (La Nació and Iberia). The myth of the 12,000 “voluntaris catalans” thus began to be forged.

Germanophile Crusade against Anti-Spanish Sentiment↑

Spanish Germanophiles were characterized by their defence of strict neutrality, rejecting the government’s neutral ally policy, while openly demonstrating their support for the Central Powers. It is usually claimed that political Germanophilia held a positive view of neutrality. However, this was a minority position among the intellectual class. Those who seconded it included Vicente Gay (1876-1949), Pío Baroja (1872-1956), José María Salaverría (1873-1940), Jacinto Benavente (1866-1954), and Juan Vázquez de Mella (1861-1928).

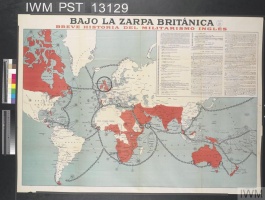

On the whole, they held that the rapprochement with the Entente was a huge mistake for Spanish national interests. Historically, Great Britain and France had used every opportunity to demean and humiliate the Spaniards, refusing whatever belonged to the country, by disrupting its integrity or depriving it of the prolongation of its territory. From the Napoleonic invasion to Gibraltar and Tangiers, examples were plentiful. Vázquez de Mella expressed this very emphatically at the La Zarzuela Theatre in May 1915: “To be Anglophile one had to be Hispano-phobic.”[14] In this context, the war represented an ideal opportunity for the Spanish nation to shake off the lethargy imposed by the influence of France and Great Britain and focus on its own project of Iberian reconstruction. This was a very appealing view for Spanish Germanophiles. The conservative politician Antonio Maura would attract tens of thousands of them to a neutralist meeting hosted at the Madrid bullring in April 1917.

Despite being a minority current in intellectual circles, Germanophilia possessed an excellent social advocacy mechanism in the Spanish Church and in magazines like El Debate or the Jesuit Razón y Fe. The country’s ecclesiastical publications were overtly hostile to England and France. To this was added the official doctrine’s strong anti-liberal stance, which also had a huge influence on the young conservative followers of Maurism. As a matter of fact, for those in charge of Allied propaganda in Spain this was the reason why they had almost given up the fight for public opinion. The allegations of Cardinal Desiré-Joseph Mercier (1851-1926) with respect to German atrocities against a Catholic country like Belgium impressed the bishops to some degree, though they did not manage to mitigate the strong anti-Allied sentiment that prevailed. France and Great Britain embodied laicism and the absence of spiritual values, thus being incompatible with the true essence of the Spanish spirit.

Conclusion↑

The neutral countries had to justify their place in a world at war, defining themselves from the perspective of otherness and with their own identity traits, while asserting the agency of their states. The war not only reached Spain via press articles or the personal accounts of returning emigrants, but was also a reality for many Spaniards who were trapped in a circle of commercial vetoes and submarine attacks. The need to understand the neutral political stance against belligerent interference fostered different social visions of being Spanish. So, investigating a Spanish neutrality linked with inner identity processes due to alterity to belligerents is a very suggestive path for current research since it gives new insights into the momentous divorce between the “Real Spain” and the “Official Spain”.

Carolina García Sanz, University of Seville

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ López Alcón, Noemí: La Narrativa Breve y la Crónica de Guerra (1900-1945). Estudio Interdiscursivo y Comparado (thesis), University of Murcia 2015, p. 71, pp. 124-144.

- ↑ Barreiro Gordillo, Cristina: España y La Gran Guerra a Través de la Prensa, in: Aportes 29/84 (2014), pp. 165-166.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: British Blacklists in Spain during the First World War. The Spanish Case-study as a Belligerent Battlefield, in: War in History 21/4 (2014), p. 501.

- ↑ Bello, Luis: España durante la Guerra. Política y Acción de los Alemanes, 1914-1918, Madrid 1920, p. 8.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: La Primera Guerra Mundial en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Economía, Política y Relaciones Internacionales, Madrid 2011, p. 178.

- ↑ Lacomba, Juan Antonio: La Crisis de 1917, Madrid 1970, p. 15.

- ↑ Meaker, Gerald H.: A Civil War of Words. The Ideological Impact of the First World War on Spain, 1914-1918, in: Schmitt, Hans A. (ed.): Neutral Europe Between War and Revolution, 1917-1923, Charlottesville 1988, pp. 1-66; Romero Salvadó, Francisco J.: Spain 1914-1918. Between War and Revolution, London 1990.

- ↑ Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: The Great War as an Expression of the Dispute Between the “Two Spains”, in: Pla, Xavier / Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano / Montero, Francesc (eds.): A Civil War of Words. The Cultural Impact of the Great War in Catalonia, Spain, Europe and a Glance at Latin America, Bern 2016, pp. 197-226.

- ↑ Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: España en la Primera Guerra Mundial. Una Movilización Cultural, Madrid 2014, p. 48.

- ↑ Ortega y Gasset, José: La Política de Neutralidad, la Camisa Roja, in: España, 29 January 1915; Política de Neutralidad, Italia Resuelta, in: España, 19 March 1915; Archilés Cardona, Ferran: Una Nación Descamisada. Ortega y Gasset y su Idea de España Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial (1914-1918), in: Rubrica contemporánea 4/8 (2015), pp. 29-47.

- ↑ Anthropos Revista de Informacion y Documentacion 50 (1985), p. 67.

- ↑ Araquistain, Luis: Un Pueblo Narcotizado, in: España, 17 May 1917.

- ↑ Martínez Fiol, David / Esculies Serrat, Joan: Identidades Cruzadas, Identidades Compartidas. Españolidad y Catalanidad en los Voluntarios Españoles de la Gran Guerra, in: Rubrica Contemporánea 4/7 (2015), p. 77.

- ↑ Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: Imperialismo e Iberismos en España. Perspectivas Regeneradoras Frente a la Gran Guerra, in: Historia y Política 33 (2015), p. 28.

Selected Bibliography

- Archilés Cardona, Ferran: Una nación descamisada. Ortega y Gasset y su idea de España durante la Primera Guerra Mundial (1914-1918), in: Rúbrica contemporánea 4/8, 2015, pp. 29-47.

- Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: España en la Primera Guerra Mundial. Una movilización cultural, Madrid 2014: Akal.

- Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: Imperialismos e iberismos en España. Perspectivas regeneradoras frente a la Gran Guerra, in: Historia y política 33, 2015, pp. 21-48.

- García Sanz, Carolina: La Primera Guerra Mundial en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Economía, política y relaciones internacionales, Madrid 2011: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- García Sanz, Carolina: British blacklists in Spain during the First World War. The Spanish case study as a belligerent battlefield, in: War in History 21/4, 2014, pp. 496-517.

- García Sanz, Carolina / Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: Toward new approaches to neutrality in the First World War. Rethinking the Spanish case-study, in: Ruiz Sánchez, José-Leonardo / Cordero Olivero, Inmaculada / García Sanz, Carolina (eds.): Shaping neutrality throughout the First World War, Seville 2016: Editorial Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 39-62.

- Lacomba, Juan Antonio: La crisis española de 1917, Madrid 1970: Editorial Ciencia Nueva.

- Martínez Fiol, David; Esculies Serrat, Joan: Identidades cruzadas, identidades compartidas. Españolidad y catalanidad en los voluntarios españoles de la Gran Guerra, in: Rubrica Contemporanea 4/7, 2015, pp. 77-99.

- Meaker, Gerald H.: A civil war of words. The ideological impact of the First World War on Spain, 1914-1918, in: Schmitt, Hans A. (ed.): Neutral Europe between war and revolution, 1917-23, Charlottesville 1988: University Press of Virginia, pp. 1-65.

- Pla, Xavier / Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano / Montero, Francesc (eds.): A civil war of words. The cultural impact of the Great War in Catalonia, Spain, Europe and a glance at Latin America, Oxford 2016: Peter Lang.

- Romero Salvadó, Francisco J.: Spain 1914-1918. Between war and revolution, London 1999: Routledge.