Submarines and Prize Law↑

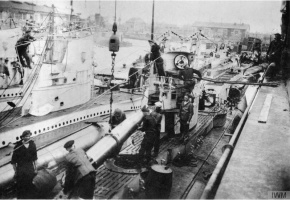

The world’s major naval powers began fielding “modern” submarines in the decade leading up to the First World War. Armed with effective torpedoes and a mine-laying capability, they served as coastal defense weapon systems and posed a threat to even the most powerful warships of the enemy. When the war opened in 1914, Britain possessed the largest submarine force with seventy-five boats, while France and Germany had fifty and thirty, respectively.

As the stalemate developed on the Western Front and Britain’s blockade of German trade became increasingly effective, German naval leaders explored the idea of using submarines as commerce raiders. Additionally, by early 1915 the Royal Navy had largely neutralized the German surface raider threat to merchant shipping.

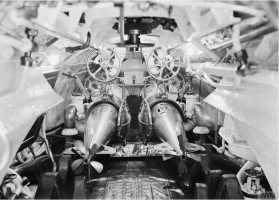

While submarines could attack warships without warning, internationally recognized Prize Law prescribed a relatively strict set of norms for naval vessels capturing or sinking enemy merchant vessels. Accordingly, the rules mandated that naval vessels had to stop and search the merchant vessel and account for the safety of the crew, either by taking them on the warship, providing a prize crew to lead the merchant vessel to a friendly port, or by putting them into life boats in close proximity to land. Submarine captains put their vessels and crew members at risk by carrying out these rules when they surfaced to conduct an inspection. They also normally could not spare crew members to act as a prize crew and had no capacity to take interned merchant crew members onboard the submarine.

The First U-Boat Campaign↑

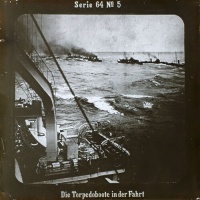

In response to the British blockade and declaration of the North Sea as a war zone, German leaders decided to embark on a counter blockade using U-boats to sink merchant shipping. On 4 February 1915, the German government declared the waters around Britain and Ireland a war zone, threatening destruction of all “enemy” merchant vessels and issuing a warning to neutrals. Ships would be sunk without warning, in clear violation of the Prize Rules.

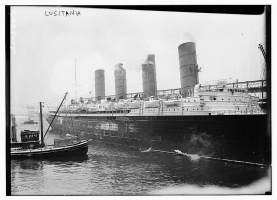

The Germans found immediate success, initially sinking approximately two ships per day by employing a force of thirty operational U-boats. Lacking anti-submarine weaponry and tactics, British attempts to counter the U-boats were ineffective. On 7 May 1915, U-20 torpedoed the RMS Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, a disaster that caused the death of 1,198 civilians, including 128 Americans, and brought immediate protest from the US government. The Germans countered that the Lusitania was carrying war contraband - which it was - and ignored US complaints. On 19 August, U-24 attacked the SS Arabic, killing three Americans and driving Woodrow Wilson's (1856-1924) administration to threaten breaking diplomatic relations. The German government relented and stated that attacks against passenger liners would henceforth be forbidden. At this point, the Germans confined their U-boats to the North Sea using Prize Rules for encounters there, and switched their focus to Mediterranean trade routes, thus ending the first U-boat campaign.

The campaign had been costly for the British, especially during the summer months of 1915. However, when compared to the total volume of merchant traffic on the high seas, losses were relatively light. As historian Paul Halpern explains, from the start of the war through September 1915, total losses in merchant tonnage approximately equaled new construction.[1]

The Second U-Boat Campaign↑

German naval leaders decided to seek a new U-boat campaign in the waters surrounding Britain in early 1916. Using the widespread arming of merchant vessels as justification, they gained approval from the German government to carry out unrestricted submarine warfare, with orders to spare passenger liners. The second campaign began on 1 March with fifty-two operational U-boats available to the Germans.

Germany ran into diplomatic problems almost at once, with strong protests from the Dutch and American governments. On 24 March, UB-29 torpedoed the Sussex, injuring three Americans. The US government once again threatened war, and on 24 April the German government ordered the navy to follow Prize Rules. Disgusted with his government’s decision, High Seas Fleet Commander Reinhard Scheer (1863-1928) recalled his U-boats and employed them with the fleet in support of North Sea operations.

This brief submarine campaign accounted for 143 ships sunk in March and April 1916, and the Germans lost four U-boats in the same period. Though short in duration, British losses were a cause for concern as merchant shipping production slowed due to other demands of the British war machine.

The Final U-Boat Campaign↑

The Germans faced a continuing stalemate on land and at sea in late 1916, causing naval leaders to develop a proposal for resuming unrestricted submarine warfare. Basing their calculations on existing British high seas trade, the Germans estimated that by sinking 600,000 tons of British merchant vessels per month for six months, they would paralyze the British economy, scare neutrals away from the British Isles, and force a surrender before the Americans could substantively intervene on the Western Front. Indeed, the German Chief of the Naval Staff insisted that no American soldiers would reach Europe. The British would be forced to surrender or starve. Now, with 105 operational submarines, the Germans began their final U-boat campaign on 1 February 1917 with Wilhelm II, German Emperor's (1859-1941) blessing.

| Month | German Figures

(Gross tons) |

British Figures

(Gross tons) |

| Feb 1917 | 520,412 | 497,095 |

| Mar 1917 | 564,497 | 553,189 |

| Apr 1917 | 860,334 | 867,834 |

| May 1917 | 616,316 | 589,603 |

| Jun 1917 | 696,725 | 674,458 |

| Jul 1917 | 555,514 | 545,021 |

| Aug 1917 | 472,372 | 509,142 |

Table 1: Entente and Neutral Shipping Losses to U-boats, February to August 1917[2]

Entente and neutral shipping losses were severe from February through June 1917, with peak losses from submarines reaching 860,334 tons in April.[3] The US declared war against Germany on 6 April. In late April the British adopted a convoy system for shipping inbound to the British Isles. With more escort vessels available from the US Navy, including improved anti-submarine weaponry employing depth charges, mines, and aircraft patrols, and expanded the use of convoys, the final U-boat campaign became less and less effective. Convoys made it difficult for U-boats to locate their targets; instead of numerous independent vessels plying the seas, ships would now be grouped in larger but fewer formations. Convoys also forced German U-boats to attack well-defended groups of merchant vessels, an extremely dangerous endeavor.

In early 1918, the Germans shifted their attacks to the coastal waters around Britain, in an attempt to sink vessels as the convoys dispersed to their intended ports of call. An initial spike in losses in January and February 1918 caused the British some concern, but the introduction of coastal convoys with heavy escorts soon neutralized this new threat. Between May and November 1918, the Germans sent six long-range U-boats to operate in American coastal waters. These U-boats sank ninety-three ships but most were sailing vessels or small steamers.[4]

As a strategy of economic warfare, the U-boat campaigns of the First World War were a failure, largely due to diplomatic pressure from neutrals and eventual British and Allied countermeasures. German U-boat captains failed to block the flow of US troops to Europe. The German and British experience of submarine warfare would inform future strategic considerations during World War Two.

John Abbatiello, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Corbett, Julian S.: History of the Great War. Naval operations, 5 volumes, London 1920-1931: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Halpern, Paul G.: A naval history of World War I, Annapolis 1994: Naval Institute Press.

- Herwig, Holger H.: 'Luxury fleet'. The imperial German navy, 1888-1918, London; Boston 1980: Allen & Unwin.

- Lundeberg, Philip K.: The German naval critique of the U-boat campaign, 1915-1918, in: Military Affairs 27/3, 1963, pp. 105-118.

- Spindler, Arno: Der Handelskrieg mit U-Booten, 5 volumes, Berlin; Frankfurt a. M. 1932-1966: E.S. Mittler & Sohn.

- Tarrant, V. E.: The U-boat offensive, 1914-1945, Annapolis 1989: Naval Institute Press.