Events Leading to the War↑

The autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland in the northwestern Russian Empire stayed out of the First World War. No Finnish troops were conscripted into the Russian army. Accordingly, not until the collapse of the tsarist regime in February 1917 and the ensuing struggle for power did the armed struggle seem likely to reach Finland.

The Parliament (eduskunta), led by the Social Democrats, declared Finland semi-independent by issuing the Law of Supreme Power (valtalaki) in July 1917. This order left only foreign and military policy in the hands of the Russian Provisional Government. The Russian Provisional Government, with support from the Finnish middle class parties, ultimately disbanded the Finnish parliament. In the new election the bourgeoisie claimed a victory, which caused bitterness among socialists and polarized the political situation. The ongoing World War and social unrest in the empire resulted in food shortages and unemployment, further fuelling the crisis.

After the October Revolution in early November 1917, the Finnish workers’ movement declared a general strike, and clashes between the workers’ Red Guards and the middle class Civil Guards ensued. These guards had been established to fill the power vacuum left by the disbandment of the gendarmerie in March 1917. In the wake of the October Revolution the bourgeois Finnish government started to seek a way to separate Finland from Russia, but socialists sympathetic to the Bolsheviks discouraged such a separation. On 6 December 1917, parliament declared Finland's independence. On the last day of the year, the Bolshevik government formally granted Finland its independence.

The War Breaks Up↑

The struggle for power and arming of the guards continued to intensify after formal ties to Russia were cut. The leadership of the rather moderate Social Democratic Party remained reluctant to seize power until the social situation and the pressure from the more radical Red Guards became intolerable. Many of the socialist demands, such as an eight-hour workday, were met before the war started. Still, the course towards conflict became unstoppable. While the socialists prepared for a possible takeover, the government prepared for an armed conflict by declaring the bourgeois Civil Guards the state’s army. Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867–1951), lieutenant general in the Imperial Russian Army, was appointed commander-in-chief of the government troops.

There were clashes in January leading up to the date historians accept as the start of the war, namely 27 January 1918. On that night, the Red Guards seized power in the Finnish capital of Helsinki and declared a revolution. Simultaneously, the White Civil Guards began the disarmament of Russian troops on Ostrobothnia, the western coast of Finland. The number of Russian troops stationed in Finland had decreased during 1917, but at the beginning of the war around 40,000 troops were garrisoned in the country. The last of those soldiers in southern Finland retreated on 3 March 1918, according to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Troops and Theaters of War↑

At the onset of the war a number of leading members of the government fled from Helsinki to Vaasa in Ostrobothnia. They formed the so-called White Senate. The Reds, for their part, set up a revolutionary government, the Delegation of People’s Commissars (kansanvaltuuskunta).

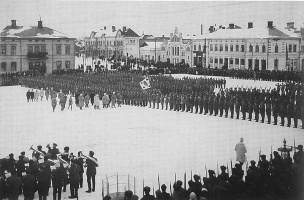

The Red troops consisted primarily of urban and rural labourers. They occupied the industrialized southern Finland. At its strongest the Red military organisation employed 100,000 men and women, including unarmed maintenance troops, of which perhaps 80,000 were in arms simultaneously, including 2,000 women. Russian participation in battles remained low, although the Bolsheviks supported the Reds on the Karelian front near Petrograd. The White troops occupied the mostly rural areas north of Tampere. At first, the troops consisted of volunteer and drafted Civil Guardsmen; then, from late February onwards, the White Army was supplemented with conscripted soldiers and 1,000 Swedish volunteers. Approximately 1,200 Finnish Jägers, anti-Russian activists trained by the German Army since 1915, returned to Finland in February to take part in the war. Their combat experience and leadership provided the Whites with an advantage over the Reds. The armed strength of the Whites was 80,000–90,000 men, out of which 55,000–60,000 were on the front. Two-thirds of the front line troops were conscripts. Although the White Army was better-equipped and more organised than the Reds, the war was essentially fought between inexperienced amateur armies. This changed after a request by the White Senate to secure victory in early April 1918 and establish German positions around the Gulf of Finland. Subsequently, the German Baltic Sea Division of 10,000 men, commanded by Major General Rüdiger von der Goltz (1865–1946) and the detachment Brandenstein comprising 3,000 men, commanded by Colonel Otto von Brandenstein (1865-1945), landed in southern Finland.

The Reds held the military lead until mid-March and secured control of the southern towns and countryside. But the White Army soon gained momentum and rapidly outmaneuvered the Reds. The White Army would have defeated the Red Guards eventually even without the German expedition. The decisive victory was achieved with the Battle of Tampere, which ended on 6 April with casualties of at least 2,000 men and women. The Germans conquered Helsinki on 13 April, and the last battles between the guards were fought in southeastern Finland in late April and early May, including the conquest of Vyborg on 29 April. The White victory was formally declared on 16 May.

The Casualties↑

The short conflict caused the death of more than 38,000 persons (including 2,000 Russians and other foreign nationals), which amounted to greater than 1 percent of the total population of 3.2 million people. Approximately 28,000 casualties were Finnish Reds. Battle casualties numbered 6,600 Reds and 3,900 Whites, including foreign nationals. Both sides resorted to take-no-prisoner tactics, but the White terror, lawless field court-martials, and local victors’ retributions proved to be notably grimmer with over 10,000 victims. The number of Red terror casualties was 1,650. The biggest number of deaths, however, unfolded in the prisoner of war camps set up for the Reds and their supporters, where 12,500 people perished amid hunger and the Spanish flu epidemic during the summer and autumn of 1918. At the peak more than 80,000 people were interned in the camps.

Causes and Consequences of the War↑

The Finnish Civil War started as an offshoot of the October Revolution. It was, however, primarily an internal struggle until the German Army intervened, making southern Finland a theater of the First World War. Two factors were crucial in causing the conflict: the power vacuum in the country and class divisions. The power vacuum came about when the collapse of the tsarist regime and later the Bolshevik Revolution destroyed societal restraints; this vacuum opened up unexpected possibilities for intertwined ideologies of national independence and class struggle. Class divisions were heightened in the rapidly modernizing society.

Due to the German defeat in the First World War, Finland did not affiliate with the collapsed monarchical empire as planned, but instead was declared a republic in 1919. Nevertheless, the war resulted in a divided society. A large segment of the population lost their civic rights, notably the rights to vote and participate in elections, after their release from prisoner-of war camps. Most of the released prisoners regained their rights in the early 1920s. Furthermore, 10,000 people fled to Soviet Russia. The victors called the Finnish Civil War the "War of Liberation," denoting freedom from Russia and the Bolsheviks. The victors claimed their opponents had been under Bolshevik influence and overemphasized the role of Russians in the conflict. These divisions started to dissipate in the late 1930s but were not overcome until the Second World War. The true scale of the White terror was not acknowledged until the 1960s.

Tuomas Tepora, University of Helsinki

Section Editor: Piotr Szlanta

Selected Bibliography

- Alapuro, Risto: State and revolution in Finland, Berkeley 1988: University of California Press.

- Haapala, Pertti / Hoppu, Tuomas (eds.): Sisällissodan pikkujättiläinen (Encyclopedia of the Finnish Civil War), Helsinki 2009: W. Söderström.

- Tepora, Tuomas / Roselius, Aapo (eds.): Finnish Civil War 1918. History, memory, legacy, Leiden; Boston 2014: Brill.

- Tikka, Marko: Kenttäoikeudet. Välittömät rankaisutoimet Suomen sisällissodassa 1918 (Court-martial without law. Punitive measures in the Finnish Civil War of 1918), Helsinki 2004: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Upton, Anthony F.: The Finnish Revolution, 1917-1918, Minneapolis 1980: University of Minnesota Press.