Introduction↑

Whereas earlier research has mainly concentrated on the treatment and experience of POWs, more recent studies have highlighted the significance of POWs as part of the broader political transformations connected to the First World War, particularly concerning the role of POWs in state-building and in the export of political ideas (as in the case of Revolutionary Russia).[1] This gives the field a much broader relevance for the history of the emergence of independent states in East Central Europe, such as Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States.

During the First World War, over three million Poles and hundreds of thousands of soldiers from the Baltics were mobilised into the imperial armies of Austro-Hungary, Russia, and Germany.[2] Thus from the Polish perspective, the First World War could be characterised as a Polish Civil War. This fact was well known even prior to the start of the hostilities. Just a few hours before the outbreak of the German-Russian war, the daily newspaper Dziennik Bydgoski commented:

This statement proved to be true. For example, in opposite trenches near Łowczówek in Galicia during Christmas 1914, Polish legionnaires fighting on the Austro-Hungarian side and Polish soldiers from the Russian Siberian Rifle took turns singing stanzas of Polish Christmas songs.[4] Of one Cracovian bookseller's twelve nephews, eight served in the Austro-Hungarian army, two in the Russian army, one in the Prussian army, and one in the American army.[5]

It is likely that a few hundred thousand of East Central Europeans fell into captivity, though no statistical details are available. Beyond the ordinary problems of POWs such as malnutrition, hunger, infectious diseases, insects, lack of suitable clothes, longing for family and friends, boredom, monotony of life, overcrowding, dirty quarters, mistreatment at times, and hard physical work, these POWs were exposed to intensive propaganda campaigns aimed to abandon loyalty to the state they served and join the voluntary units fighting on the side of their formal enemies to regain Polish independence or establish Estonian, Latvian, or Lithuanian nation states.

Though interest in the history of POWs on the Eastern Front has risen in the last few years, an imperial perspective still dominates the research. The experiences of different nations, whose members served in the multinational Russian and Austro-Hungarian armies, have not been given enough consideration by historians of the Great War. These topics are also not especially popular in the national historiography of Poland and the Baltic states.

Poland↑

Entente States↑

At the beginning of the war, Polish POWs in Russia from the Central Powers’ armies were treated well as Slavic brothers. However, when they refused to form voluntary units, as did some Czechs and Slovaks, they were accused of being traitors to the Slavic cause and thus subjected to worse treatment.[6] Some Polish POWs, along with soldiers of other nationalities, working in severe climate conditions, constructed the Murmań Railway. Others were interned in Turkestan where they also constructed railways or were employed in cotton fields.[7] The best living conditions were experienced by those who were sent to the countryside to help farmers. They enjoyed a wider range of freedom and often a higher standard of living than at home. Some of them bonded with local women and planned to stay in Russia after the war ended.[8] Paradoxically, relatively decent living conditions prevailed for POWs in eastern Siberia.[9]

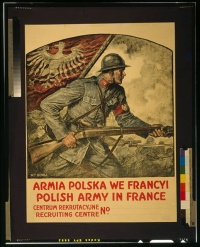

Special camps for German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers of Polish nationality were also organized in France, Great Britain, and Italy. Especially after 1917, when the Polish National Committee, a kind of unofficial government-in-exile, was established in Paris, these soldiers were encouraged to join the Polish army in France. The separate camps that existed for Poles were organized by the British in Felthan, a suburb of London, and in France in Longenau and by the French authorities on the island of Belle-Île and in Miliana, Algeria. From the summer of 1915, Polish POWs from the German army were placed in camps in Le Puy, Montluçon, and Vierzon.[10] Up to the spring of 1919, 20,000 soldiers went through camps for Polish POWs in France.[11] At the end of the war about 15,000 Austro-Hungarian POWs of Polish nationality, concentrated in two camps near Naples, Cassagiove and Santa Maria Capua Vetera, were imprisoned by the Italians.[12]

Central Powers↑

From the very beginning of the war Polish POWs from the tsarist army were regarded by the German authorities as potentially interested in serving against the Russian empire.[13] Especially in the second phase of the war in late 1916, the Central Powers planned the establishment of a new Polish army to fight against Russia. To give a legal basis for this project, William II, German Emperor (1859-1941) and Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) announced 5 November 1916 “The Declaration of Two Emperors” which reestablished an independent Polish State in the Russian part of Poland, a constitutional monarchy to be allied with the Central Powers.

The first step in forming Polish units was the concentration of Polish POWs from the Russian army in separate camps. At that time, German camps were comprised of about 60,000 Russian POWs of Polish nationality. They were asked to submit their willingness to be moved to the special POW camps located in Ellwagen and Helmstedt for officers and in Celle and Gardelegen for soldiers.[14] Captured Polish officers of the tsarist army were summoned to special propaganda camps where with movies, lectures, and carefully selected books the camp authorities tried to indoctrinate them into “a true picture of Germany.”[15] They could also observe national holidays and were visited by Austro-Hungarian officers of Polish nationality and civil national activists from the Danube Monarchy. They also enjoyed better living conditions than other officers of the Russian army. Furthermore, some of the Polish POWs were granted a short leave to visit their homes located in areas occupied by German or Austro-Hungarian troops.[16] In 1917, Piotr Głasek, an unknown soldier, complained in a letter sent from a Hungarian POWs camp to his mother and confiscated by censors:

Despite propagandistic efforts, the majority of POWs remained indifferent to patriotic agitation and preferred to stay in German and Austro-Hungarian POW camps until the end of hostilities, rather than joining the Polish army with the risk of losing their lives in the trenches or by execution resulting from being kept on the battlefield by former brothers of arms. The motivations of the small group who did join the volunteers were diverse: some did it for patriotic reasons, others just wanted to get out of the camp under any pretext. As one observer, Józef Jadaczyk, noted, probably with exaggeration, they would be ready to join any army, even Chinese, only to free themselves from the barbed-wire zone.[18] Those who decided to move to special POW camps for Poles hoped for better living standards or wanted to change their social environment. Only 180 Polish officers from the Russian army decided to join the Polish army. Sixty-eight of them arrived in Warsaw in December 1916. About 1,000 Poles from the Russian army were taken prisoner by Turkish and Bulgarian troops. In October 1917 all were released.[19]

Relations between Polish POWs and ethnic Russians worsened after the declaration of 5 November 1916. As a result, Russian POWs in Germany started to look at their Polish comrades as potential traitors. In some camps, Poles were excluded from the distribution of material aid sent by the Russian government with the excuse “that they are now citizens of the other state.”[20] In the second half of 1917, German authorities, disappointed by the weak response to their endeavors, lost interest in forming a Polish army.

Relief Actions↑

The civil war dimension of the First World War for the Polish nation had some positive aspects for Polish POWs. Namely, they could count on the help of their compatriots who were subjects of a hostile state. For example, in autumn, 1914, the Polish POWs, who were transported via Warsaw to internal provinces of Russia, were provided by inhabitants of the city with warm clothes, shoes, and gloves.[21] In Tyumen, western Siberia, a Polish colony organized a special women’s committee to support Polish POWs in the local camp.[22] Delegates of Poles, among them Stanisław Trzeciak (1873-1944), a lecturer from a Roman Catholic Seminary in Petrograd, visited the construction site of the Murmań Railroad to control the living and working conditions of POWs.[23]

Due to the lack of a Polish state institution, the burden of helping Polish POWs rested on the shoulders of society and non-government organizations. Such committees for POWs functioned in many Polish towns and abroad in Vevey and Freiburg in Switzerland and Leiden in Holland.[24]

In sum, despite the endeavors of the Polish national activists, Polish POWs’ loyalty toward Russia, Germany, and Austria was surprisingly enduring. As mentioned above, the majority of Polish POWs from the Russian army showed indifference to the Polish national cause and even mocked those active in that area.[25] The same applied to the Polish POWs from the Habsburg Army in Russia, where many soldiers and officers, even of Polish nationality, tried to dissuade those wanting to join the Polish national troops with threats of denunciation to the Austrian authorities after the war.[26] At times, there was conflict between Polish POWs from different regions of partitioned Poland but placed in one camp. In French camps Poles from the German province of Posen quarreled with those from the German province of Silesia, regarding them as too loyal to the German state.[27] Endeavors aimed at convincing Polish POWs from the German army to reinforce the ranks of the Polish Blue Army in France returned more than modest results. Only 10 percent of soldiers in the 1st Rifle Regiment had previously served in the German or Austro-Hungarian armies.[28]

The Fate of Former Legionaries↑

After refusing to take a new oath of fidelity to the German emperor in July 1917, three brigades of Polish legionaries were dissolved and their soldiers, former Russian citizens, interned in camps Szczypiorno and Beniaminów.[29] One of the main occupations of interned legionnaires was playing handball and from that time on the sport was unofficially called “szczypiorniak” after the camp in Szczypiorno.

Some of the legionnaires, mostly from the Second Brigade and Austro-Hungarian citizens, decided to continue fighting and joined the Polish Auxiliary Corps. After the conclusion of the Brest Litovsk Treaty between the Central Powers and the Ukrainian National Republic in February 1918, in which the Chełm Land (Chełmszczyzna) was given to the Ukraine – which Polish public opinion unanimously regarded as extremely unfavorable to the Polish cause – soldiers of the Polish Auxiliary Corps decided to go over to the Russian side of the front line. Only a part of this group managed to fight through the front line. The majority were surrounded by Austro-Hungarian troops and forced to lay down their arms. In the next months, the former legionnaires were interned in camps where they awaited the judgment of high-treason, processed mainly in eastern-north Hungary (Huszt, Máramarossziget, Dulfvalf, Bustyahaza, Szeklencze). The Polish public opinion in Galicia regarded them as martyrs for the Polish cause, supporting them morally, materially, and legally while intensively lobbying for their release. Interpellation in their name was submitted by the Polish deputies to the Austrian parliament and they were defended by the best Polish attorneys. Finally, in the last days of September 1918, the Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922) granted them a pardon.[30]

Baltics and Finland↑

Finnish POWs had a particular experience during the First World War. The Grand-Duchy of Finland was completely excluded from Russian conscription until 1902, which resulted in mass refusals to serve and opposition to the draft. After two years of protests, the Russians gave up, the attempt to enact conscription in Finland was abandoned, and the draft was replaced with a payment, the so-called “military millions,” paid regularly from the budget of the Grand-Duchy to the Empire. As result, during the First World War only about one thousand Finnish volunteers served in the Russian army. On the German side about 1,600 Finns fought. Only a small number of Finns serving in the Russian army were taken prisoners. In POW camps they were simply placed among the other Russian soldiers. A few of them joined the Jäger movement. The most prominent was Wilhelm Thesleff (1880-1941), who served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Russian army in 1914-1917 and was captured by the Germans on the Riga Front. He decided to join the Finnish Jäger Battalion and returned to Finland with the Germans in 1918. For a very brief time in 1918 he served as minister of war in Finland.

Most Baltic POWs interned in Germany were from Lithuania due to the swiftness of the Great Retreat of 1915 and the ensuing rapid occupation of Lithuania and southern parts of Latvia. While it is difficult to establish precise numbers, it is safe to say that almost 20,000 Lithuanians and more than 5,000 Latvians were interned as POWs in Germany. Thanks to the relatively small population size and the late occupation of Estonia in February 1918, only around 2,700 Estonian POWs were interned in Germany.[31] POWs from the Baltics were interned along with other – mostly Russian – soldiers of the imperial Russian army. In 1916 a monument was erected in Schneidemühl (Piła) to commemorate Polish, Lithuanian, and Latvian soldiers who had died in the POW camp there.

In 1917, German agents systematically infiltrated POWs from the Baltics to identify potential collaborators – especially among the officer corps – who could act as representatives for Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania at the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk to provide legitimacy to German territorial claims. However, these efforts were frustrated by the relatively low degree of national fervor among interned soldiers from the Baltics.[32] Activists within Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, on the other hand, demanded the return of all POWs before any aspects of state building under German tutelage (such as the election of national assemblies) could start.

After the November Armistice, national committees for the repatriation of POWs were formed in the Baltic States in the context of broader repatriation efforts. In Lithuania, a Committee for the Repatriation of Prisoners of War was established at the end of 1918 and attached to the delegation to the Paris Peace Conference.[33] However, repatriation was thwarted by the continuing state of war in the region. The Allied Supreme War Council attempted to act as a central organizer for the repatriation of POWs, planning to ship Estonians directly to Tallinn or Saaremaa. Russian POWs were to be sent by rail through Lithuania via Kaišiadorys. This plan had to be abandoned as a consequence of fighting around Vilnius.[34] Alternative plans to repatriate Russian POWs through Latvia were called off because of Latvian and international worries that as long as a quick passage through Bolshevik lines was not guaranteed, the emerging state would very likely be destabilised by soldiers in transit, who were suspected to harbour Bolshevik tendencies. The Allies also considered transporting Russian soldiers via Danzig directly to Narva at the Russian border. Moreover, the Western Entente worried that a quick repatriation would block desperately needed maritime transport and in turn strengthen the Red Army.[35] In July 1919, the Allied Supreme Council estimated that 15,400 Lithuanians, 5,300 Latvians, and 2,300 Estonians were still awaiting repatriation, some of whom were considered fit for further military service against the Red Army, but most of whom were deemed too severely weakened by their internment.[36]

The influx of returning POWs to the Baltics provided a desperately needed pool of recruits for the emerging national armies and for paramilitary units, which fought in the Wars of Independence and the Russian Civil War. Vilnius, in particular, which was fought over by the Polish army, the Lithuanian army, and the Red Army, became a hub for the recruitment of POWs.[37] The continuing wars and border conflicts resulted in further soldiers taken prisoner and interned in makeshift camps, for instance Lithuanian POWs in Poland and Latvian POWs in Lithuania.[38]

Conclusion↑

Prisoners of war from East Central European nations shared the fate of their brothers-in-arms, serving in the imperial armies of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. However, especially in the second part of the war, when the pre-war political and territorial status quo was undermined by prolonged war, some decided to join national units aimed at fighting on the side of former enemies for establishing new nation states.

Piotr Szlanta, University of Warsaw

Klaus Richter, University of Birmingham

Section Editors: Ruth Leiserowitz; Theodore Weeks

Notes

- ↑ Nachtigal, Reinhard: The Repatriation and Reception of Returning Prisoners of War, 1918–22, in: Immigrants & Minorities 26/1-2 (2008), pp. 157-184; Leidinger, Hannes and Moritz, Verena (eds.): Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917-1920, Vienna 2003; Rachamimov, Alon: POWs and the Great War. Captivity on the Eastern Front, New York 2002.

- ↑ Czerep, Stanisław: Straty polskie podczas I wojny światowej [Polish loses during the First World War], in: Grinberg, D. / Snopko, J. / Zackiewicz, G. (eds.): Lata Wielkiej Wojny. Dojrzewanie do niepodległości 1914–1918, [Years of the Great War. Growing towards independence 1914-1918], Białystok 2007, pp.180-181.

- ↑ Wobec wrzenia wojennego [On war crisis], Dziennik Bydgoski, 1 August 1914.

- ↑ Składkowski, Felicjan Sławoj: Moja służba w Brygadzie [My service in the Brigade], Warszawa 1990, p.60.

- ↑ Sobieski, Wacłąw: Dzieje Polski [History of Poland], vol.3, Warsaw 1983, p.139. See also: Szlanta, Piotr: Wielka Wojna polsko-polska. Polacy w szeregach armii zaborczych podczas pierwszej wojny światowej. Zarys problematyki [The Great Polish Civil War. Poles in Ranks of Imperial German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Armies during the First World War. A survey], in: Baczkowski, Michal / Ruszała, Kamil (eds.): Doświadczenia żołnierskie Wielkiej Wojny. Studia i szkice z dziejów frontu wschodniego I wojny światowej 1914-1918 [Soldiers’ experience of the Great War. Studies on the East Front in the First World War 1914-1918], Cracow 2016, pp. 51-77.

- ↑ Nachtigal, Reinhard: Privilegiensystem und Zwangsrekrutierung. Russische Nationalitätenpolitik gegenüber Kriegsgefangenen aus Österreich-Ungarn, in: Oltmer, Jochen (ed.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn 2006, pp.175-176; Smolik, Przecław: Przez lądy i oceny (Sześć lat na Dalekim Wschodzie) [Across lands and oceans (Six years in the Far East)], Warsaw et al., 1922, pp. 13-14; Brändström, Elsa: Unter Kriegsgefangenen in Rußland und Sibirien 1914/1920, Leipzig 1927, p. 113; Polacy w Turkiestanie w okresie wojny światowej [Poles in Turkestan during the World War], Warsaw 1931, pp.68-69; Szuścik, Jan: Pamiętnik z wojny i niewoli 1914-1918 [Memoirs from war and captivity 1914-1918], Cieszyn 1925, pp. 100, 127-128.

- ↑ Skąpski, Rafał (ed.): Na frontach I Wojny Światowej. Pamiętniki: Szczepan Pilecki, Bolesław Skąpski [On the First World War’s fronts. Memoirs of Szczepan Pielcki and Bolesław Skąpski], Warsaw 2015, pp. 144-150.

- ↑ Dyboski, Roman: Siedem lat na Syberii (1915-1921). Przygody i wrażenia [Seven years in Siberia (1915-1921). Adventures and impressions], Warsaw 2007 pp. 80-81; Bohdanowicz, Stanisław: Ochotnik [Volunteer], in: Karta 44 (2005), p. 30.

- ↑ Dziubińska, Jadwiga: Położenie jeńców wojennych w Rosji za dawnego rządu [The situation of POWs in Russia under the rule of the old goverment], Piotrogród 1917, pp. 34-38.

- ↑ Felthman, Brian K.: The Stigma of Surrender. German Prisoners, British Captors, and Manhood in the Great War and Beyond, Chapel Hill 2015, pp. 60-61; Watson, Alexander: Fighting for Another Fatherland. The Polish Minority in the German Army, 1914–1918, in: English Historical Review CXXVI/522 (2011), p. 1160.

- ↑ Wawrzyński, Tadeusz: Plany wykorzystania jeńców Polaków w czasie I wojny światowej [Plans for the use of Polish POWs during the First World War], in: I wojna światowa na ziemiach polskich. Materiały sympozjum poświęconego 70. Rocznicy wybuchu wojny [The First World War on Polish territories. Materials from the symposium on the seventieth anniversary of the outbreak of the war], Warsaw 1986, pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Janik, Michał: Obraz antyaustriackiej propagandy kierowanej do Polaków walczących na froncie włoskim w 1918 r. [Picture of anti-Austrian propaganda directed to the Poles fighting on the Italian front in 1918], in: Grinberg, D. / Snopko, J. / Zackiewicz, G. (eds.): Rok 1918 w Europie Środkowo-wschodniej [1918 in East-Central Europe], Białystok 2010, pp. 511-531; Wawrzyński, Plany wykorzystania 1986, pp. 182-184.

- ↑ Nagornaja, Oxana / Mankoff, Jeffrey: United by barbed wire. Russian POWs in Germany, national stereotypes, and international relations, 1914–22, in: Kritika. Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 10/3 (2009), pp. 482-483.

- ↑ Wawrzyński, Plany wykorzystania 1986, pp. 176-178.

- ↑ Nachtigal, Richard: Kriegsgefangenschaft an der Ostfront 1914 bis 1918. Literaturbericht zu einem neuen Forschungsfeld, Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Rokoszny, Józef: Diariusz Wielkiej Wojny 1915-1916 [Diary of the Great War], vol. 2, Kielce 1998, pp. 267-268.

- ↑ Moritz, Verena: Zwischen Nutzen und Bedrohung. Die russischen Gefangenen in Österreich 1914-1921, Bonn 2005, p. 139.

- ↑ Jadaczyk, Józef: W obozie jeńców [In POW camp], Sosnowiec 1917, pp. 43-44, 70.

- ↑ Wawrzyński, Plany wykorzystania 1986, pp. 176-180.

- ↑ Jadaczyk, W obozie jeńców 1917, p. 50.

- ↑ Kurman, Marjan: Z wojny 1914-1921. Przeżycia, wrażenia i refleksje mieszkańca Warszawy [On the War 1914-1921. Experiences, impressions and reflections of an inhabitant of Warsaw], Warsaw 1923, p. 42.

- ↑ Szuścik, Pamiętnik 1925, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Nachtigal, Reinhard: Die Murmanbahn 1915 bis 1919. Kriegsnotwendigkeiten und Wirtschaftsinteressen, Remshalden 2007, pp. 71-98; Brändström, Elsa: Unter Kriegsgefangenen in Russland und Sibirien 1914/1920, Leipzig 1927, p. 109.

- ↑ Jadaczyk, W obozie jeńców 1917, pp. 7, 46, 52; Jeńcom Polakom [For Polish POWs]. Warsaw 1918, p. 5; Polacy w Turkiestanie 1931, pp. 70-75; Dyboski, p.40.

- ↑ Jadaczyk, W obozie jeńców 1917, p. 24, 43.

- ↑ Bohdanowicz, Ochotnik 2005, p. 25; Grzesiowski, Franciszek: Wspomnienia z niewoli rosyjskiej 1915-1921 [Memoirs from Russian captivity 1915-1921], Lwow 1931, pp. 11-13; Szuścik, Pamiętnik 1925, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Kaczmarek, Ryszard: Polacy w armii kajzera na frontach I wojny światowej [Poles in the Kaiser’s army on the First World War’s fronts], Crawcow 2014, pp. 494-495.

- ↑ Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Polski czyn zbrojny podczas pierwszej wojny światowej, 1914-1918 [The Polish military contribution during the World War, 1914-1918], Warsaw 1990, pp. 462, 467; Wawrzyński, Plany wykorzystania 1986, p. 181.

- ↑ Snopko, Jan: Finał epopei Legionów Polskich 1916-1918 [The final of epic of the Polish Legions 1916-1918], Białystok 2008.

- ↑ Strachoń, Mateusz: Likwidacja Polskiego Korpusu Posiłkowego w 1918 roku. Losy legionistów po traktacie brzeskim [Liquidation of the Polish Auxilliary Corp in 1918. Fates of the legionnaires after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk], Warsaw 2013; Snopko, Finał epopei 2008.

- ↑ Tamošiūnienė, Milena: Karo belaisviai Lietuvos Respublikos politikoje, 1919 – 1923 [Prisoners of War in the politics of the Lithuanian Republic, 1919 – 1923], Vilnius 2014, p. 18; Telegram to British Mission. 6 July 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, p. 180; Report on the Means of Repatriation of Russian Prisoners now in Germany and Maintained at the Cost of the Allies. 25 July 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, pp. 223-227.

- ↑ Die litauische Konferenz in Stockhholm. Geheim. 23 June 1917. Bundesarchiv (Lichterfelde), R 901/72832, pp. 2-18.

- ↑ Tamošiūnienė, Karo belaisviai 2014.

- ↑ Maréchal Foch au Président du Conseil. 26 April 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, pp. 79-82.

- ↑ Russian Prisoners of War entering Latvia. 7 July 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, p. 171.

- ↑ Telegram to British Mission. 6 July 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, p. 180; Report on the Means of Repatriation of Russian Prisoners now in Germany and Maintained at the Cost of the Allies. 25 July 1919. The National Archives, FO 608/203, pp. 223-227.

- ↑ Uspenskij, Aleksandr: Aref’evi\vc (Uspenskis Aleksandras). “I-as Gudų Pulkas Gardine Ir Kaip Jis Tapo Lenkų Nuginkluotas: 1918. XI. I. - 1919. VIII. 17” [The 1st Belarusian Regiment in Grodno and how it was disarmed by the Poles], Karo Archyvas 1 (1925), pp. 161-176.

- ↑ Tamošiūnienė, Karo belaisviai 2014, p. 123.

Selected Bibliography

- Dziubińska, Jadwiga: Położenie jeńców wojennych w Rosji za dawnego rządu (The situation of POWs in Russia under the rule of the old goverment), Saint Petersburg 1917.

- Eglit, Liisi: The experience of returning. Estonian World War I soldiers’ return to society, in: Dornik, Wolfram / Walleczek-Fritz, Julia / Wedrac, Stefan (eds.): Frontwechsel. Österreich-Ungarns 'Großer Krieg' im Vergleich, Vienna 2014: Böhlau, pp. 71-90.

- Esse, Liisi: Eesti sõdurid Esimeses maailmasõjas. Sõjakogemus ja selle sõjajärgne tähendus (Estonian soldiers in the First World War. The war experience and its postwar meaning), thesis, Tartu 2016: Tartu University.

- Hinz, Uta: Gefangen im Grossen Krieg. Kriegsgefangenschaft in Deutschland 1914-1921, Essen 2006: Klartext Verlag.

- Janik, Michał: Żołnierze armii austro-węgierskiej narodowości polskiej w rosyjskiej niewoli 1914-1918. Wybrane zagadnienia (Austro-Hungarian soldiers of Polish nationality as prisoners of war in Russia 1914-1918. Selected issues), in: Baczkowski, Michał / Ruszała, Kamil (eds.): Doświadczenia żołnierskie Wielkiej Wojny. Studia i szkice z dziejów frontu wschodniego I wojny światowej 1914-1918 (Soldiers’ experience of the Great War. Studies on the East Front in the First World War 1914-1918), Krakow 2016: Towarzystwo Wydawnicze, pp. 201-217.

- Janik, Michał: Obraz antyaustriackiej propagandy kierowanej do Polaków walczących na froncie włoskim w 1918 roku (Picture of anti-Austrian propaganda directed to Poles fighting on the Italian front in 1918), in: Snopko, Jan / Zackiewicz, Grzegorz / Grinberg, Daniel (eds.): Rok 1918 w Europie Środkowo-wschodniej (1918 in East-Central Europe), Białystok 2010: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, pp. 511-531.

- Kaczmarek, Ryszard: Polacy w armii kajzera na frontach pierwszej wojny światowej (Poles in the Kaiser’s army on the First World War’s fronts), Krakow 2014: Wydawnictwo Literackie.

- Leidinger, Hannes / Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917-1920, Vienna 2003: Böhlau.

- Moritz, Verena / Leidinger, Hannes: Zwischen Nutzen und Bedrohung. Die russischen Kriegsgefangenen in Österreich (1914-1921), Bonn 2005: Bernard & Graefe.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: Die Murmanbahn 1915-1919. Kriegsnotwendigkeiten und Wirtschaftsinteressen (2 ed.), Remshalden 2007: Greiner.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: Russland und seine österreichisch-ungarischen Kriegsgefangenen (1914-1918), Remshalden 2003: Greiner.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: The repatriation and reception of returning prisoners of war, 1918-22, in: Immigrants & Minorities 26/1-2, 2008, pp. 157-184.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: Kriegsgefangenschaft an der Ostfront 1914 bis 1918. Literaturbericht zu einem neuen Forschungsfeld, Frankfurt a. M.; Oxford 2005: P. Lang.

- Nagornaja, Oxana Sergeevna; Mankoff, Jeffrey: United by barbed wire. Russian POWs in Germany, national stereotypes, and international relations, 1914–22, in: Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 10/3, 2009, pp. 475-498.

- Rachamimov, Alon (Iris): POWs and the Great War. Captivity on the Eastern front, New York 2002: Berg Publishers.

- Snopko, Jan: Finał epopei Legionów Polskich 1916-1918 (The final of epic of the Polish Legions 1916-1918), Białystok 2008: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.

- Tamošiūnienė, Milena: Karo belaisviai Lietuvos Respublikos politikoje, 1919-1923 (Prisoners of war in the politics of the Lithuanian Republic, 1919-1923), Vilnius 2014: Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija.

- Wawrzyński, Tadeusz: Plany wykorzystania jeńców Polaków w czasie I wojny światowej (Plans for the use of Polish POWs during the First World War), in: Stawecki, Piotr (ed.): I wojna światowa na ziemiach polskich. Materiały sympozjum poświęconego 70. rocznicy wybuchu wojny (The First World War on Polish territories. Materials from the symposium on the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the war), Warsaw 1986: Wojskowy Instytut Historyczny.