Composition↑

The First Cabinet↑

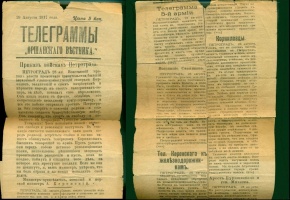

The Provisional Government was the formally constituted authority in Russia, with responsibility for the conduct of the war between February and October 1917. It was formed when the tsar’s government collapsed after protests over food shortages and unemployment gathered momentum in the last week of February 1917. Marchers demanding an end to the war and the tsarist regime were joined by mutinous soldiers from the Petrograd garrison. While crowds swelled on the street, members of Russia’s state legislature, the Duma, created the Temporary Committee to assume the work of governing the capital and restoring calm. On 2 March (15 March ), the Temporary Committee drew up a Provisional Government to run the country until authority could be handed over to a popularly-elected constituent assembly. This was the result of negotiations with the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, a revival of the workers’ councils (soviets) that had emerged in the 1905 revolution. The posts of Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior were filled by Prince Georgii Evgen’evich L’vov (1861–1925), who was head of the Union of Zemstvos, a public organization responsible for medical care, food supplies, and other aspects of Russia’s war effort. The rest of the cabinet was drawn largely from moderate Duma deputies. Pavel Nikolaevich Miliukov (1859–1943) of the liberal Kadet party took the position of Minister of Foreign affairs and Aleksandr Ivanovich Guchkov (1862–1936), leader of the conservative Octobrist party and president of the Russian Red Cross and War Industries Committees, became Minister of War and Navy. The Soviet Executive Committee gave conditional support to the government and helped draft its initial declaration, but voted against participation in the cabinet. Aleksandr Fedorovich Kerenskii (1881–1970), vice president of the Executive Committee and loosely affiliated with the Socialist Revolutionaries, nevertheless accepted the Minister of Justice role.

The Coalition Governments↑

In May 1917, following violent protests over a secret note by Miliukov to the allies committing the government to the old regime’s expansionist war aims, the Soviet Executive Committee agreed to shore up the government by allowing its socialist leaders to enter into a coalition with the liberals. Kerenskii became Minister of War and was joined by Socialist Revolutionary leader Viktor Mikhailovich Chernov (1873–1952) as Minister of Agriculture and the Mensheviks Matvei Ivanovich Skobelev (1885–1938) and Iraklii Georgevich Tsereteli (1881–1959) as Minister of Labour and Minister of Post and Telegraph, respectively. Miliukov resigned from the government and the unaffiliated liberal industrialist Mikhail Ivanovich Tereshchenko (1886–1956) took over as Minister of Foreign Affairs. When Prince L’vov resigned in July over agrarian policy, Kerenskii replaced him as Prime Minister of a reshuffled cabinet. In September, following a revolt by General Lavr Georgevich Kornilov (1870–1918), Kerenskii put together another coalition that lacked the firm support of any major political group. This was the final government before the Bolsheviks seized power.

Challenges↑

Immediate Tasks↑

The tasks before the Provisional Government and the expectations placed upon it were overwhelming. It sought to restore law and order and reconstitute administration across the empire, while introducing major political reforms and continuing to prosecute the war on the Eastern Front. Although many members of the first cabinet were constitutional monarchists by inclination, one of the cabinet’s first tasks was to oversee the end of the Romanov dynasty. Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868–1918) abdicated on 2 March (15 March) in favour of his brother, Mikhail Aleksandrovich, Grand Duke of Russia (1878–1918), who declined the crown when informed by Provisional Government leaders that they could not guarantee his safety in the event of a violent uprising.

At the same time, the new government announced its first programme, promising the convocation of an elected assembly within a short time, as well as the introduction of civil liberties. In the subsequent weeks the government enacted a raft of democratising reforms. It granted freedom of speech, assembly, and press; introduced universal adult suffrage; removed restrictions based on class, religion, or nationality: made the police accountable to local government; introduced jury trials; abolished capital punishment; and established locally-selected executive committees at every level from province to village. The initial statement by the government, however, did not deal with some of Russia’s most pressing problems, above all agrarian reform and the war, on which the government and soviet failed to agree. Regardless of its democratic programme, the Provisional Government later undertook forcible grain requisitioning, anticipating a fundamental component of the Bolsheviks’ war communism.

War, Land, and Legitimacy↑

Many of the difficulties faced by the Provisional Government stemmed from its inability or reluctance to bring the war to an end. In the first cabinet, Foreign Minister Miliukov advocated the vigorous prosecution of the war to a decisive victory and the recognition of existing treaty obligations, which included Russia‘s acquisition of Constantinople. When angry demonstrations over Miliukov’s position brought about the downfall of the first coalition government, it adopted the Soviet’s line of "Revolutionary Defencism". This entailed making efforts to achieve a general peace, without annexations or indemnities, while at the same time fighting to secure the country and the gains of the revolution against foreign military threat. Attempts by the Soviet to arrange an international socialist peace conference and the government’s efforts to persuade the Allies to revise their war aims in accordance with the "no annexations" formula came to nothing, however, while Kerenskii’s military offensive in June ended in retreat and uprisings by workers and soldiers in Petrograd.

The war effort not only alienated the government from war-weary elements of the population and army: it also continued to strain state resources, disrupt food and fuel supplies, and limit the scope of domestic social and economic reform. Reforms addressing land hunger and a fair redistribution of the land to those who worked it were the priority for much of the peasantry, who made up the majority of the population. The Provisional Government, with its respect for legal rights and consciousness of the difficulty of carrying out land reform with millions of peasants in uniform at the front, deferred passing a land law until the convocation of the Constituent Assembly. Elections to the assembly were delayed, however, by the scrupulous concern of the liberal leaders to work out a fair solution across the empire and in the army, and the distractions of military considerations and political crises. The authority of the government, which had always stressed its temporary mandate, crumbled. Peasants and deserting soldiers took land seizure into their own hands.

Crises and Collapse↑

Successive crises beset the Provisional Government in 1917, from the April crisis over war aims, to the July disturbances following the ill-fated military offensive, to the unsuccessful attempt at power from the right by General Kornilov in August. These culminated in the successful challenge from the left in October, as the Bolsheviks seized power in the name of the Soviet and promised "Peace, Land, and Bread." The government had been undermined by many factors, including the system of "dual power" whereby the Soviet possessed the only real authority over workers and soldiers, and the deepening radicalisation of the population. Economic and social dislocations caused by continued partcipation in the war were a major contributor to radicalisation, and commitment to the war effort irrevocably tainted the government in the eyes of many. In this way, the war can be considered both the midwife and executioner of the Provisional Government.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Badcock, Sarah: Politics and the people in revolutionary Russia. A provincial history, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Browder, Robert Paul / Kerensky, Aleksandr Fyodorovich: The Russian provisional government, 1917. Documents, Stanford 1961: Stanford University Press.

- Chamberlin, William Henry: The short life of Russian liberalism, in: Russian Review 26/2, 1967, pp. 144-152, doi:10.2307/127060.

- Heenan, Louise Erwin: Russian democracy's fatal blunder. The summer offensive of 1917, New York 1987: Praeger.

- Morris, L. P.: The Russians, the Allies and the War, February - July 1917, in: Slavonic and East European Review 50/118, 1972, pp. 29-48.

- Wade, Rex A.: The Russian search for peace, February-October 1917, Stanford 1969: Stanford University Press.