Youth and Education↑

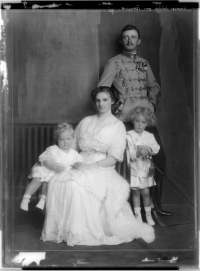

Archduke Karl Franz Joseph (1887-1922) was born on 17 August 1887 in the Castle of Persenbeug. His grandfather, Charles Louis, Archduke of Austria (1833-1896) was the brother of Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916). His father, Otto Franz, Archduke of Austria (1865-1906), had married Maria Josepha, Princess of Saxony (1867-1944), in 1877, who was strongly committed to the Catholic education of her children. Therefore, Godfried Marschall (1840-1911), later suffragan bishop, was selected as the teacher for religious education, and Onno Klopp (1822-1903), a conservative Catholic refugee from Prussian-occupied Hannover, who continually published writings against Prussian expansionism, became Charles’ teacher of history. Moreover, in 1906, the successor to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914), became Charles’ guardian and succeeded in inspiring him with enthusiasm for his own ideas for profound reform of the constitution. These were based to a certain extent on federalism, but also on the strengthening of conservative monarchic principles. Additionally, Charles was sent to the famous Viennese secondary school “Schottengymnasium” to acquire some expertise in scientific subjects.

Military Career and Engagement during World War One↑

Charles’ career as an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Army started in 1903, when he became a Lieutenant in the Regiment of Lancers (Ulanen-Regiment) Nr. 1; having transferred to the Dragoons (Dragoner-Regiment) Nr. 7 in 1905, he advanced to the rank of First Lieutenant in 1906, and Captain in 1909. Then he transferred to the infantry (Regiment Nr. 39), became a major, and, on 1 May 1914, a lieutenant colonel. After some training in the general staff and after 28 June 1914, the new successor to the throne, now a colonel, served as liaison officer to the German army in Galicia. In July 1915, he was promoted to the rank of major general, and in March 1916, to field marshal lieutenant. In spring 1916, he took part in the successful Austrian offensive in South Tyrol. In spring 1915, the German army used gas on the Western Front, which proved to guarantee quick advancement with a minimum of German casualties. In June 1916, the Austrian army decided to use this rather new weapon, too, on the Italian Front. Contemporaries, but also historians, had already criticized Charles’ role when it came to the use of gas, in particular, that he did nothing to stop it. In summer 1916, Charles became general of cavalry and on 1 November 1916, three weeks before ascending the throne of the Empire, he was promoted to the ranks of colonel general and great admiral.

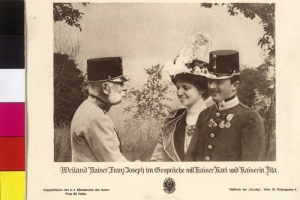

Succession to the Throne↑

When Franz Joseph died on 21 November 1916, Charles succeeded to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones and immediately assumed the title of supreme commander of the Empire’s forces, in an attempt to diminish the overwhelming German influence in their joint warfare. He and his wife, Zita, consort of Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1892-1989), were crowned King and Queen of Hungary on 30 December 1916. Thus, he was obliged to accept the political system of dualism, but, on the other hand, this system enabled him to demand universal suffrage in the Hungarian kingdom. During the two years of his regency, he was occupied with various attempts to conclude a peace treaty, even accepting serious sacrifices concerning the territorial integrity of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, like ceding parts of Tyrol to Italy. The most famous of these secret negotiations for a peace compromise is known as the Sixtus Affair, which – finally brought into focus by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottokar Graf Czernin (1872-1932) - caused the disastrous decline of independent Austro-Hungarian foreign politics and warfare.

The Struggle for Peace↑

It was in spring 1915 that the archduke proposed, for the first time, to deliver Alsace-Lorraine to France. Soon afterwards, he supported diplomatic efforts to keep Italy out of the war by means of territorial concessions. In August 1917, the Austrian diplomat Nikolaus Graf Revertera von Salandra (1866-1951) negotiated with officers of the French general staff about a separate Austro-Hungarian peace treaty, which also gave Great Britain the opportunity to present its conceptions of post-war Europe. At the same time, Pope Benedict XV (1854-1922) called for peace without any annexations and contributions. Although Charles promised to enter into an exchange of views about the future of South Tyrol with Italy, Germany refused any discussion on withdrawal from Belgium or negotiation about a cession of Alsace-Lorraine, even after Charles had offered Austrian Silesia as the utmost compensation for those territories indispensably demanded by France.

Final Efforts and Exile↑

As for interior affairs, Charles tried to stop the increasing famine by founding the Ministry of Social Welfare (1917) and the Ministry of Public Health (1918). In August 1918, he ordered Heinrich Lammasch (1853-1920) and Johannes Andreas von Eichhoff (1871-1963) to draft a new constitution based on the idea of an Austrian Commonwealth of Nations (Staatenbund). On 16 October 1918, he declared a new federalist constitution by himself which, because of the armistice on 3 November 1918 and the foundation of the Austrian republic on 12 November 1918, never came into force. On 11 November 1918, influenced by his Minister Ignaz Seipel (1876-1932) and the Archbishop of Vienna, Friedrich Gustav Piffl (1864-1932), Charles renounced any participation in government. After the armistice, the Austrian parliament demanded his abdication, which was refused by the emperor, who retired to Swiss exile on 23 March 1919. He stayed in Rorschach and Pragins, before twice moving to Hungary to push for restoration (in March and October 1921). But as he did not want to provoke a civil war after Regent Miklós Horthy (1868-1957) refused to hand over power, he was forced to give up those efforts.

The first attempt at restoration started on 26 March 1921. Having secretly negotiated with the French Prime Minister Aristide Briand (1862–1932), Charles believed that France would support him against menacing interventions from Hungary's neighbors. Charles managed to travel to Szombathely for preliminary negotiations with the Hungarian Prime Minister Pál Teleki (1879-1941). On the next day, he succeeded in meeting Regent Miklós Horthy in the Castle of Budapest, but even after an emotional two-hour discussion, Horthy refused to hand over power to the king, with the argument that this would necessarily lead to a civil war. Despite this, Charles stayed in Szombathely until 5 April 1921, expecting Horthy to change his mind. Disappointed he then returned to Switzerland.

On 20 October 1921, accompanied by his wife Zita, Charles tried again, having landed near Sopron with a small airplane. Without intending to seek compromise with Horthy, he formed a provisional government. Supported by Hungarian legitimist politicians and officers, and parts of the army, Charles tried to march to Budapest. Horthy made a military proclamation that he would retain power and demanded loyalty from his army. On 23 October, the legitimists arrived at Budaörs, a village close to the capital. The following confrontation might have led to civil war. Nineteen victims remained on the battlefield, dead. To avoid further bloodshed, Charles reluctantly agreed to armistice negotiations. He then dictated a surrender order.

Together with his family, he was sent into exile on the island of Madeira, where he died on 1 April 1922 as a result of pneumonia. In 1954, the process of beatification was initiated. Fifty years later, on 3 October 2004, he was beatified by Pope John Paul II (1920-2005).

Robert Rill, Austrian State Archives and War Archive Austria

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Broucek, Peter: Karl I. (IV.). der politische Weg des letzten Herrschers der Donaumonarchie, Vienna 1997: Böhlau.

- Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. 'Selig, die Frieden stiften-'. Die Biographie, Vienna 2004: Amalthea.

- Feigl, Erich: 'Gott erhalte-' Kaiser Karl. persönliche Aufzeichnungen und Dokumente, Vienna 2006: Amalthea.

- Kovács, Elisabeth: Untergang oder Rettung der Donaumonarchie?, 2 volumes, Vienna 2004: Böhlau.

- Mikrut, Jan (ed.): Kaiser Karl I. (IV.) als Christ, Staatsmann, Ehemann und Familienvater, Vienna 2004: Dom.