Background↑

The Sarajevo incident represented the culmination of a complex series of historical processes originating in Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina under the Treaty of Berlin of 1878. Over the following decades, the Dual Monarchy’s presence in the territory, still nominally under the rule of the Ottoman Sultan, brought it into conflict with various regional actors. Among these, Serbian nationalists proved the most antagonistic, perceiving Bosnia-Herzegovina’s large Serb minority as an integral part of a historic “Greater Serbia”. Moreover, by the turn of the 20th century, the province increasingly existed at the heart of a convoluted web of rising geopolitical tensions. In 1881, Vienna had sought, and initially obtained, Germany and Russia’s approval for the future political annexation of its new Balkan protectorate. The 1894 accession of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918), however, saw St. Petersburg renege on its earlier agreements; at the regional level, Austria-Hungary’s difficulties were further exacerbated by the overthrow of Serbia’s pro-Habsburg Aleksander Obrenović, King of Serbia (1876-1903) in 1903 and the appearance of ethnic nationalism as an integral factor in Bosnian politics by 1905. The Young Turk Revolution in July 1908 subsequently served as the catalyst for direct action by the Monarchy. In October 1908, seeking to prevent the revolution from spreading northwards while reasserting political dominance over Serbia, Vienna took advantage of the political chaos within the Ottoman Empire and Russia’s diminished military capabilities, following the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, and announced that it would be formally annexing Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Despite the initial diplomatic backlash, Austria-Hungary’s reckless actions were ostensibly successful; by 1909, even Russia and Serbia had formally recognized Bosnia-Herzegovina’s transfer of sovereignty. Nevertheless, the early 1910s witnessed a continual escalation in tensions surrounding the Monarchy’s actions, coupled with rising economic and socio-political unrest within its now expanded borders. Inspired by the Bosnian Serb Bogdan Žerajić’s (1886-1910) attempted assassination of the provincial governor General Marijan Varešanin (1847-1917) in June 1910, so-called “cultural organisations”, such as “Young Bosnia” (Mlada Bosna), became increasingly militant.

This was compounded by the appointment of the politically ambitious General Oskar Potiorek (1853-1933) as Varešanin’s successor in 1911. The new governor’s efforts to suppress anti-Habsburg activities, following Serbia’s success during the Balkan Wars, brought Young Bosnia under the influence of the Serbian nationalist Black Hand Society. Drawing on intelligence gathered by its chief operative in Sarajevo, Danilo Ilić (1891-1915), the society’s leaders initially proposed that Muhamed Mehmedbašić (1887-1943), a Bosnian Muslim affiliate, attempt to assassinate Potiorek. In March 1914, however, a new target had been chosen: Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914), who would be visiting Bosnia-Herzegovina in June 1914 to observe local military manoeuvres. As the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand’s proposals for greater political autonomy within the Monarchy’s South Slav territories posed a direct challenge to Serbian nationalist ambitions. Moreover, the timing of the Archduke’s visit was perceived as a calculated snub by the provincial government since it coincided with the Serbian national and religious holiday of St. Vitus (Vidovdan) on 28 June.

Over the following months, Ilić recruited from among Young Bosnia’s most radical student members. Three of these youths, Nedeljko Čabrinović (1895-1916), Trifko Grabež (1895-1916) and Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918), who were resident in Serbia’s capital Belgrade in 1914, received money, weapons and basic training from Black Hand operatives. The trio subsequently returned to their homeland in May. According to a later testimony from Mehmedbašić, Ilić had kept the identities of the Belgrade recruits a secret until the eve of the assassination itself. Indeed, each recruit was even issued a cyanide capsule since, like Žerajić, none were expected to survive.

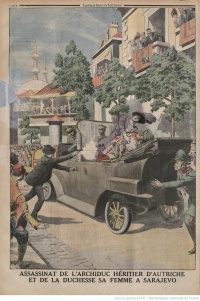

The Assassination↑

Franz Ferdinand arrived in Sarajevo on 25 June 1914. Reuniting with his wife, Sophie, Archduchess of Austria (1868-1914), the Archduke spent the following two days attending to his official duties as well as sightseeing. Princip is believed to have first observed the imperial couple as they toured the city’s famous old bazaar.

On the morning of 28 June 1914, six assassins took up positions on Appel Quey, a narrow boulevard running along the northern bank of the Miljacka River. Ilić moved between them in order to offer encouragement. Ironically, the conspirators had found an unsuspecting ally in the local authorities. Potiorek, hoping to further ingratiate himself with the Monarchy’s heir presumptive, had played down warnings of assassination plots, ignoring recent precedents such as the attempted murder of his own predecessor in 1910. Consequently, beyond a light police presence, security arrangements for the procession were notably lax. Just after 10:00 am, the Archduke’s motorcade, comprising six open-top cars, turned onto Appel Quey towards Sarajevo’s city hall. The lack of consideration afforded to security having left the vehicle in which the imperial couple travelled, with Potiorek, directly exposed to the unguarded crowds lining the street. The procession initially passed Mehmedbašić and Čubrilović, but neither reacted. Mehmedbašić later claimed that they had been deterred by the presence of a nearby police officer. As the motorcade approached the third operative, Vaso Čabrinović (1897-1990), the would-be assassin, threw a hand grenade supplied by Ilić. Rather than landing inside, the explosive glanced off the limousine’s collapsible roof and detonated under the vehicle following behind. As the royal car accelerated away, Čabrinović swallowed his cyanide capsule and attempted to throw himself into the river. In the dry summer heat, however, it proved too shallow and the poison did little more than induce vomiting; the Young Bosnian was taken into custody, prompting his allies to disperse.

At the city hall, Potiorek, concerned over the possible damage a major security debacle might cause to his political reputation in Vienna, vetoed any suggestion of mobilizing troops, arguing that the local garrison did not possess appropriate dress uniforms. Franz Ferdinand however, insisted on visiting the hospital where those injured in the explosion had been taken for treatment. At 10:45, the motorcade departed back along Appel Quey with the imperial couple again sharing the same car as Potiorek. This decision proved fatal: the Archduke’s Czech chauffeur, Leopold Lojka (1886-1923), was unaware of the revised schedule and, following the original procession route, turned right at the famous Latin Bridge. As Lojka attempted to reverse back out onto the thoroughfare, the car stalled in front of a popular delicatessen where Princip happened to be loitering. Drawing his pistol, the assassin fired twice, hitting the Archduke in the throat, and his wife in the abdomen; Princip would later state that Potiorek was the intended second target.

Like Čabrinović, Princip’s cyanide capsule failed to take effect, with police intervening before he could turn the gun on himself. The imperial couple were rushed to Potiorek’s official residence, however, the Archduchess was pronounced dead on arrival. By 11:00, Ferdinand had also succumbed to his injury.

Aftermath and Consequences↑

Following the assassinations, anti-Serb demonstrations in Sarajevo, encouraged by Potiorek, quickly devolved into rioting and pogroms while the authorities moved to arrest anyone suspected of aiding the assassins. With the exception of Mehmedbašić, who managed to escape to Montenegro, Princip’s accomplices were eventually captured and tried for murder and treason. Čubrilović and Ilić were sentenced to death and executed in 1915. By contrast, under Habsburg law, Grabež, Čabrinović and Princip were still legally minors and therefore ineligible for capital punishment. All three instead received twenty-year prison terms. None would live to see the end of the First World War, with Princip being the last to die from tuberculosis in April 1918.

The assassination’s historical importance is generally attributed to it having precipitated the July Crisis. Nevertheless, even assessed in isolation from its disastrous implications, the Sarajevo incident stands as a warning on the consequences of social unrest and political alienation.

Samuel Foster, University of East Anglia

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Albertini, Luigi: The origins of the war of 1914, London; New York 1952: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914, New York 2013: Harper.

- Dedijer, Vladimir: The road to Sarajevo, New York 1966: Simon and Schuster.

- Pfeffer, Leo / Zistler, Rudolf: Istraga u Sarajevskom atentatu (Investigation into the Sarajevo assassination), Banja Luka 2014: Besjeda.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg monarchy, 1914-1918, Vienna 2014: Böhlau.

- Remak, Joachim: 1914. The Third Balkan War. Origins reconsidered, in: The Journal of Modern History 43/3, 1971, pp. 354-366.