Pre-war Career↑

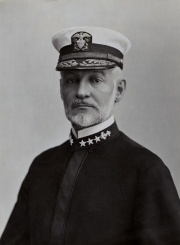

Born in Canada, William Sowden Sims (1858-1936) was the son of U.S. citizens and was eligible to attend the United States Naval Academy. Graduating in 1880, Sims spent the first years of his naval career as a punctilious student of all matters pertaining to his profession. His thorough reports on the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), while stationed onboard the cruiser USS Charleston, led to a posting as naval attaché in Paris and St. Petersburg (1897). While serving as an attaché, Sims was impressed by the qualitative superiority of European navies in relation to ship design and gunnery. The place of his birth and his appreciation of European navies would invite criticism at various points in Sims’ career.

Returning to sea duty in Asian waters (1901), Sims became acquainted with British naval gunnery specialist Captain Percy Scott (1853-1924) and his system of continuous firing for improved accuracy. Sims became a devotee of the system and went so far in his advocacy for its adoption by the U.S. Navy that, upon meeting with the obstinacy of the American naval bureaucracy, he brought the matter directly before President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). Rather than berate the young officer for his insubordination, Roosevelt gave him the opportunity to prove the value of the system. American gunnery improved and Sims, confirmed in his unorthodox approach to dealing with red tape, remained an outspoken champion for all matters that he believed beneficial to the navy throughout his career.

The United States Enters the War↑

In a 1910 address at London’s Guildhall, Sims outlined a future that included unbreakable Anglo-American ties in the event of a threat to the British Empire. As the United States was not aligned with any foreign power, Sims’ statement of unflinching American support in the tumultuous years preceding the outbreak of World War I drew a stern rebuke from President William H. Taft (1857-1930), yet presaged Sims’ efforts as the U.S. Navy’s chief coordinator in Europe during the Great War. Serving as the president of the U.S. Naval War College (USNWC) in 1917, Sims was detailed in late March to secretly travel to London and serve as a liaison with the Admiralty in anticipation that the United States might enter the war. By the time Sims arrived, the United States was indeed at war as an associated power. Sims acted forcefully to shape the relationship between the two navies into a very close partnership that entailed placing American naval forces under British operational control.

Upon entering the war on 6 April 1917, the most pressing concern for the United States was the same as that for Britain: bringing an end to the threat posed by German submarines. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (1859-1935), Britain’s First Sea Lord, was frank with the Americans as to the dire state of affairs confronting the burgeoning partnership. The U.S. Navy was not well prepared for war. Having arrived in London as a junior Rear Admiral, Sims did not sit idly by awaiting directions from Washington. Instead, he pleaded for the disbursement of American anti-submarine warfare (ASW) assets to Britain while also becoming an advocate for the convoy system. While not the originator of the idea to employ convoys, Sims was uniquely placed to argue for a greater allocation of American naval forces to make convoys more effective and their use more widespread. The Navy Department quickly recognized Sims as indispensable. He was promoted to Vice Admiral in late May and given command of U.S. destroyers operating from British bases. A month later he was designated Commander, United States Forces Operating in European Waters.

Despite the accumulation of titles, Sims did not serve as the operational commander of American naval forces operating against Germany’s U-boats. When American destroyers arrived for duty in Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland, they were placed under the command of British Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly (1857-1938). Sims had tremendous respect for Bayly and good relations between the two admirals led to an effective partnership. Between the work of the destroyers operating from British waters and the convoys operating under the direction of U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves (1858-1937), the threat from submarines declined and American ground forces arrived in steadily increasing numbers for service on the Western Front.

Aftermath↑

Sims emerged from the war extremely critical of Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels (1862-1948) and what Sims considered the service’s tardy responses to his requests for ASW resources and a general lack of preparedness for war. Resuming his pre-war position at the Naval War College, Sims was a central figure in a divisive public airing of grievances with Daniels that played out in hearings before the United States Senate. Sims also collaborated with Burton J. Hendrick (1870-1949) to produce a memoir of his experiences in the recently concluded war. Their product, The Victory at Sea, would win the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1921. More importantly, Sims’ return to the Naval War College meant that he would influence the views of a new generation of American naval leaders. After coordinating the U.S. Navy’s efforts in European waters during the First World War, Sims would reinvigorate a War College that sharpened the intellects of naval officers who would garner acclaim for their efforts plotting the Navy’s course to victory in the Second World War. Through the War College, Sims’ influence extended beyond his days on active duty (which ended with mandatory retirement in 1922). Admirals Ernest J. King (1878-1956), Chester W. Nimitz (1885-1966), and Raymond A. Spruance (1886-1969) were students of the War College who would become famous as America’s most capable naval commanders during World War II.

Chuck Steele, United States Air Force Academy

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Halpern, Paul G.: A naval history of World War I, Annapolis 1994: Naval Institute Press.

- Kohnen, David: The U.S. navy’s Great War centurion, in: Naval History Magazine 31/2, 2017, pp. 14-19.

- Morison, Elting Elmore: Admiral Sims and the modern American navy, Boston 1942: Houghton Mifflin.

- Sims, William Sowden: The victory at sea, Annapolis 1984: Naval Institute Press.

- Trask, David F.: William Sowden Sims. The victory ashore, in: Bradford, James C. (ed.): Admirals of the new steel navy. Makers of the American naval tradition 1880-1930, Annapolis 1990: Naval Institute Press, pp. 282-299.