Pre-War↑

Manfred von Richthofen (1892-1918) was born to an aristocratic family in Breslau, Prussia, (now Wrocław, Poland). His younger brother, Lothar von Richthofen (1894-1922), would also gain notoriety as a fighter pilot during the First World War. Manfred’s upbringing reflected his aristocratic background. He excelled at horse riding and hunting, and later enrolled in a German military academy. Following school, Richthofen enlisted in the army and soon joined an elite Uhlan cavalry unit.

World War I↑

The outbreak of the First World War and the rapidly changing nature of warfare quickly rendered horse-mounted cavalry units obsolete. Realizing that he would see little combat, Richthofen transferred to the Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (the Imperial German Flying Corps). Richthofen, however, struggled as an aviation student and even noted how disconcerting his first flight was. Following flight training, he served as an observer on the Eastern Front with the Feldflieger Abteilung 69 in the summer of 1915. During this period, Richthofen met a rising aviator named Oswald Boelcke (1891-1916), who persuaded him to train as a pilot to move beyond observation duties. Richthofen did so, and while his difficulties in the air continued, he eventually gained confidence as an aviator.

Richthofen and Boelcke met again in August 1916. By this time, Boelcke had gained enormous public fame for shooting down several enemy aircraft. The famous ace recruited Richthofen to join his squadron, Jasta 2, on the Western Front. The unit was comprised of aviators who showed promise, and Richthofen achieved his first aerial victory on 17 September 1916. Richthofen was an ardent student of the “Dicta Boelcke,” an early codification of combat rules written by his mentor. Boelcke, however, was killed in October 1916 following a mid-air collision with a fellow squadron member. Only a month later, Richthofen achieved one of his most well-known aerial victories when he shot down British aviator Lanoe Hawker (1890-1916) over the frontlines.

By January 1917, Richthofen was credited with sixteen victories and subsequently earned Prussia’s highest military honor, the Pour le Mérite. Richthofen then was given command of his own squadron, Jasta 11. Richthofen was renowned as a squadron leader, and he mentored his fellow pilots, many of whom became notable aces, including his younger brother, Lothar. As a result, Jasta 11 soon became one of the most successful hunting squadrons on the Western Front.

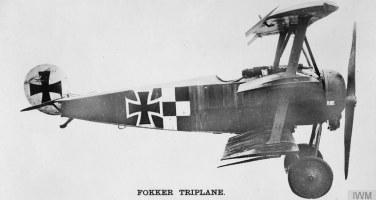

Richthofen’s score rose rapidly in April 1917, a period known as “Bloody April” for the severe losses suffered by the British Royal Flying Corps. By the end of the month, Richthofen’s tally stood at fifty-two victories. His success earned him the command of an even larger unit, Jagdgeschwader 1, which was comprised of several Jasta squadrons. Jagdgeschwader 1 was soon nicknamed the “Flying Circus,” both for its continual movement along the Western Front and for the bright color schemes flown by its pilots. Richthofen’s machine was recognized by its bright red paint scheme, which earned him the moniker “The Red Battle Flier” and later, “The Red Baron.” Richthofen also penned a heavily edited autobiography, Der Rote Kampfflieger (The Red Battle Flier), which detailed his experiences as Germany’s most celebrated fighter pilot.

In July 1917 he was badly wounded after being shot in the head while attacking a formation of British aircraft. He was forced to land while nearly blinded by the blood from his wound. Though he attempted to return to service, Richthofen was eventually forced to take convalescent leave during the late summer and autumn of 1917. After returning to service his score continued to rise until he downed his 80th opponent on 20 April 1918.

The next day Manfred von Richthofen was shot down and killed over enemy territory near the Somme River. He had chased an enemy Sopwith Camel low over enemy lines. The events surrounding his death led to decades of speculation as to whether Richthofen was killed by Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown (1893-1944), as reported at the time, or by ground fire. Later research showed almost conclusively that Richthofen was killed by a single round, likely fired by an Australian ground unit. He was buried with full military honours.

Perhaps more important than Richthofen’s influence in the air was his role as a popular hero in Germany during the war. Like Boelcke before him, Richthofen’s public image drew a large popular following. His memoir was an instant success and became the second bestselling war book of the conflict. Popular postcards produced by the publisher Sanke featuring Richthofen were collected during and after the war. Richthofen’s most significant contribution as a popular hero was in providing Germans with some sense of knowable victory. With the Western Front stalled, Richthofen’s ever-growing tally of victories created some sense of quantifiable victory. Subsequent propaganda depicted a successful military hero who was victorious in his own war, even as the wider war was moving in the opposite direction. The cult of the mythological hero also made aerial combat knowable and relatable to the German public, and often repackaged medieval tropes to make a new kind of violence accessible to a home front hungry for positive news.

Post-War↑

Following the First World War, Richthofen’s body was exhumed and returned to Germany in 1925. During the Third Reich, Richthofen’s autobiography was reissued with a new introduction by Hermann Göring (1893–1946), who extolled Richthofen as an example to guide the Nazi rearmament of the new German Luftwaffe. In doing so, Richthofen was repackaged yet again, from the cult of the hero of the First World War to a re-imagined idol for a new National Socialist Reich.

Robert Rennie, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Burrows, William E.: Richthofen. A true history of the Red Baron, New York 1969: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Kilduff, Peter: Richthofen. Beyond the legend of the Red Baron, New York 1994: John Wiley & Sons.

- Morrow, John Howard: German air power in World War I, Lincoln 1982: University of Nebraska Press.

- Richthofen, Manfred von: Der rote Kampfflieger, Berlin 1917: Ullstein.

- Schilling, René: 'Kriegshelden'. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813-1945, Paderborn 2002: Schöningh.