Military Career↑

Influence and Reform↑

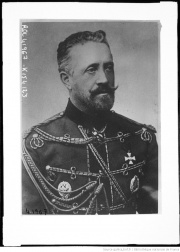

Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929) and first cousin of Alexander III, Emperor of Russia (1845-1894), was immersed in Russia’s military milieu. He trained at St. Petersburg’s Military Engineering School and General Staff Academy and served in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 on the staff of his father, who was Commander-in-Chief during the conflict. As Inspector-General of Cavalry from 1895, Nikolai Nikolaevich gained a reputation as a moderniser. Amidst the disasters of Russia’s war with Japan and the revolutionary unrest and calls for political reform of 1905, the Grand Duke assumed the posts of Commander-in-Chief of the St. Petersburg Military District and Chairman of a newly created State Defence Council, intended to provide cohesion to Russia’s organs of state security, reform the empire’s military institutions and coordinate war planning. Anton Kersnovskii concludes that Nikolai’s sway over military affairs between 1905 and 1908 was so pervasive that this can be termed the “Grand Ducal period” of the army.[1] The extent of his influence, however, is hard to measure and was limited by the jealous guarding of executive powers by Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918). The recommendations of the State Defence Council required the Tsar’s approval and did not always coincide with his priorities, particularly his naval leanings. The Tsar’s preference for departments and institutions working in isolation and subordinate only to him meant that relations between the Council, government ministries, and general staffs of the army and navy were beleaguered by ambiguity over spheres of competence mutual ignorance, and rivalry. Financial constraints and internal policing demands also impeded the reinvigoration of Russia’s armed forces. By 1908 some progress had been made, for example the introduction of higher pay, shortened terms of service, and culling of dead wood from the officer corps. However, the Council drew criticism from both the imperial bureaucracy and the Duma, the state parliament, and was disbanded. Greater strides were made in technical and organisational reform in subsequent years, but institutional fragmentation continued to destabilise Russian preparations for war.

Wartime Role↑

In early 1912, Nikolai Nikolaevich used his influence as a senior officer and member of the royal family to support a generals’ revolt against the defensive Mobilisation Schedule of 1910 that had been developed by War Minister Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov (1848-1926) in case of European conflict. The resulting compromise, Schedule No. 19, planned for offensive operations directed against Austria-Hungary without precluding simultaneous efforts against Germany, a scheme which disastrously divided Russian forces in 1914. Nikolai may also have contributed to Russia’s decision in July 1914 to respond to Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia with preparations for war. He had opportunity to express his martial, pro-Slav outlook at a crucial meeting of the Council of Ministers and in private conversation with the Tsar. Nevertheless, he was probably surprised at his nomination as Commander-in-Chief and took charge at Stavka (Russian Headquarters) without detailed knowledge of operational plans. Commentators disagree over the control Nikolai Nikolaevich exercised over developments on the Eastern Front. It was difficult for anyone to impose their vision on army command, which was divided into separate, sometimes antagonistic, fronts and into supporters of Sukhomlinov and his enemies, who cleaved to Stavka. Norman Stone, moreover, locates power at Stavka in the hands of Quartermaster General Iurii Nikiforovich Danilov (1866-1937) and refers to Nikolai Nikolaevich as a mere figurehead. Paul Robinson, though, argues that the Grand Duke’s personality at times made a crucial impact. Nikolai’s inclination to allow his commanders latitude gave the army flexibility to repulse enemy attacks at Warsaw in September-November 1914, but lack of coordination reduced the effectiveness of the Russian counter-offensive. His Francophilia encouraged the early attack on Germany to divert forces away from the Western Front, and his preference for offensive manoeuvres meant the army expended resources holding positions captured in western Poland months after the inconclusive Battle of Lodz, on-going munitions shortages, and defeats at the Masurian Lakes and Gorlice-Tarnow made this untenable. In August 1915, with Russian troops retreating, the Tsar removed Nikolai Nikolaevich to Viceroy of the Caucasus and assumed Supreme Command himself. The decision was not purely military, but was also influenced by the Tsar’s sense of duty, the antipathy of the Alexandra, Empress, consort of Nicholas II (1872-1918) to the Grand Duke, and Nikolai’s interference in civilian affairs.

Civil Authority↑

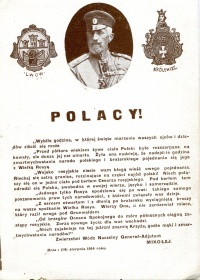

Nikolai Nikolaevich professed loyalty to the Tsar and ignorance of civilian politics. Nevertheless, his influence, particularly as Supreme Commander, extended beyond the armed forces. A statute on wartime administration granted the army leadership almost complete control over civilian affairs in territory adjacent to the front. In practice, this subjected an area encompassing the Jewish Pale of Settlement, most of Ukraine, the Baltic provinces, Belarus, Poland, Finland, the Caucasus, Petrograd and much of Central Asia and the Far East to military rule. In the political sphere, Nikolai’s narrow, martial focus meant he was amenable to concessions if circumstances demanded but could also be arbitrary, brutal and reactionary. In 1905, he had been instrumental in persuading Nicholas II to grant a constitution and parliament to avert continued public unrest. During the First World War, he put his name to a proclamation promising self-government for a future united Poland and, to the consternation of the Tsar, showed a willingness to work with Duma liberals and support the involvement of entrepreneurs in the war economy. He also, however, interfered with legal process to ensure that Lieutenant-Colonel Sergei Nikolaevich Miasoedov (1865-1915), a Sukhomlinov protégé accused of espionage, was tried by field court martial. Miasoedov, who was most likely innocent, was promptly found guilty and executed. In territories under military control, Nikolai Nikolaevich failed to curtail abuses of the civilian population. Mistreatment ranged from requisitioning and destruction of property to rape and anti-Jewish pogroms and drove hundreds of thousands of people eastwards as refugees. Nikolai intervened against forced conversions of the Uniate population in Galicia to Orthodoxy by the local army administration but encouraged persecutory measures, such as arrests, hostage-taking and mass deportations, against enemy subjects and Russian-subject Germans and Jews regarded as traitors and spies. The actions of the military authorities created administrative chaos, radicalised affected groups, dissipated the good will of the wider population toward the wartime government and linked patriotism to something other than the Romanov dynasty – a concept of the ethnic nation or a strong military leader. Cultivation of spy-mania further undermined the regime’s legitimacy, fostering rumours of rampant treason that eventually tainted the German-born Empress Alexandra and German-sounding Prime Minister Boris Vladimirovich Shtiurmer (1848-1917).

Assessments↑

The corrosion of trust in Russia’s rulers did not dent the Grand Duke’s popularity. When Nicholas II resolved to replace Nikolai Nikolaevich at Stavka, the Emperor received messages expressing popular support for the Grand Duke, along with demands for a government enjoying public confidence. The Tsar’s Council of Ministers itself begged the sovereign to reconsider, earning his approbation. After Romanov rule was overthrown in February 1917, the Provisional Government briefly considered restoring Nikolai to Commander-in-Chief. Instead, he spent two years in the Crimean Peninsula before fleeing the Bolshevik’s Red Army and settling in France, where, despite polemical attacks by Sukhomlinov, he was central to frustrated hopes for restoring the monarchy. On his death, commentators such as Alfred Knox (1870-1964), British liaison officer to the Imperial Russian Army during the war, hailed him as a true patriot, leader and statesman, although some fellow émigrés noted his indecision and irresponsibility. Historian Boris Kolonitskii has explored how wartime propaganda, rumour and myth-making elevated Nikolai Nikolaevich to a symbol of courage and patriotism. Military blunders and meddling in civilian affairs were blamed at the time, as by many historians since, on Chief of Staff General Nikolai Nikolaevich Ianushkevich (1868-1918), and the Grand Duke continued, despite his inadequacies and aloofness, to be perceived as a national saviour, even as new military and civilian candidates for this status were emerging.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Notes

- ↑ Kersnovskii, A. A.: Istoriia Russkoi Armii. Tom. III (1881-1917gg.) [History of the Russian Army, Volume III], Belgrade 1935, p. 589.

Selected Bibliography

- Graf, Daniel W.: Military rule behind the Russian front, 1914-1917. The political ramifications, in: Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 22/3, 1974, pp. 390-411.

- Kersnovskii, Anton Antonovich: Istoriia russkoi armii (1881-1917 gg.) (History of the Russian Army (1881-1917)), volume 3, Belgrade 1935: Tsarskii.

- Kolonit͡skiĭ, Boris: 'Tragicheskaia erotika'. Obrazy imperatorskoi sem’i v gody pervoi mirovoi voiny ('Tragic eroticism'. Images of the Imperial family during the First World War), Moscow 2010: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

- Robinson, Paul: Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. Supreme commander of the Russian army, DeKalb 2014: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.