Early Life↑

James Ramsay MacDonald (1866-1937) was born into rural poverty on 12 October 1866 in Lossiemouth, a fishing port in north east Scotland. Moving south, his industry, determination, and talent brought him into the House of Commons in 1906 as Labour Member for Leicester. His earliest politics were Radical Liberal but he joined the ethical socialist Independent Labour Party in 1894. He became the principal architect of the alliance between the ILP and the trade unions that would form the Labour Party. Handsome, emotional, and tactically flexible, he was Labour’s dominant figure by the summer of 1914.

Opposition↑

On 3 August 1914 MacDonald spoke in the Commons as chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) in response to Sir Edward Grey’s (1862-1933) statement that war with Germany was imminent. He opposed British involvement. His position reflected his roots in radical Liberalism and his commitment to the Socialist International. Two days later he was abandoned by the majority of Labour MPs who decided to vote for the war credits. He immediately resigned as chair of the PLP. Within weeks, his indictment of the government had widened. He argued that the roots of the war lay in the system of alliances that, through mutual suspicion, had destroyed the balance of power. Escalation had been facilitated by the insulation of diplomats from democratic institutions. MacDonald rapidly became involved with Liberal politicians who opposed entry into the war. The outcome was the Union of Democratic Control (UDC) which articulated his diagnosis of the crisis and campaigned for the democratisation of foreign policymaking.

For the duration of the war, MacDonald’s allies were the networks around the UDC and the ILP. Yet he never endorsed what would become the latter’s pacifist position. Rather he supported an Allied victory but opposed the erosion of liberal values and practices that was an inevitable concomitant of a lengthy conflict and an increasingly interventionist state. Such complexities were hard to articulate; predictably, MacDonald became the target of xenophobic hysteria, accused of pro-German sympathies, his meetings sometimes broken up, his illegitimacy proclaimed in a jingoistic weekly. Equally, he was for many on the left the personification of principled resistance to state authoritarianism and mob rule. He was championed by many who did not share the nuances of his position.

Political Fortunes↑

His position within the Labour Party was weak. From the formation of the Asquith Coalition in May 1915, the party was represented within the government; the introduction of military conscription was backed by Labour ministers and eventually accepted by the labour movement. MacDonald and the ILP as with many others were in the minority. The formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916 meant a further onslaught on liberal decencies. Yet the Labour Party never split over the war. Acerbities between trade union patriots and ILP socialists could be unpleasant but basic unity was maintained. Arthur Henderson (1863-1935), Labour’s senior minister and MacDonald had limited empathy but shared a commitment to unity. In 1917, with mounting war weariness, the prospects for the British left improved.

The collapse of Tsarism gave hope across the European left that the war could have a constructively progressive outcome. MacDonald’s attempt to visit Petrograd was backed by the Lloyd George government, keen to strengthen Aleksandr Kerenskii's (1881-1970) administration, but was foiled by an ultra-patriotic seamen’s leader who vetoed his sailing from Aberdeen. Although MacDonald’s hopes for the viability of the Russian government proved mistaken, the summer of 1917 left a crucial legacy for British Labour and eventually for MacDonald. In August, Henderson left the government. His differences with MacDonald remained significant but they could co-operate on an agenda that covered a peace without annexations or indemnities and the need for the Socialist International to be a force in the making of a post-war world. By December 1917, the labour movement supported a memorandum that endorsed much of the agenda of the UDC.

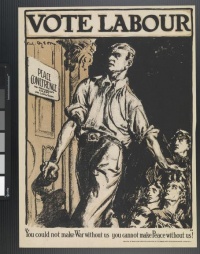

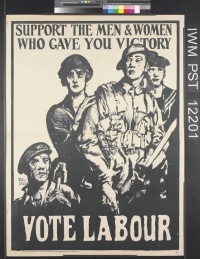

When the war ended and David Lloyd George (1863-1945) called a snap election, a Labour Party conference endorsed MacDonald’s view of the party fight s a force independent of the coalition. This went against the view of most Labour MPs but reflected wider party opinion. The campaign fought in the aftermath of military victory fostered a vicious onslaught on those who could be presented as anti-war. In Leicester, MacDonald has been sustained by a strong ILP branch and sympathetic trade union activists. This fidelity counted for little in a contest dominated by calumny and caricature; his defeat was overwhelming.

Legacies↑

MacDonald returned to the Commons in the November 1922 election. He was immediately elected chair of the PLP and, in effect, the Labour Party’s first leader. Fourteen months later, the vicissitudes of three-party politics brought him into office as prime minister in a short-lived minority government. He also acted as foreign secretary. The international policies that had seemed utopian less than a decade earlier were attractive and credible in the pacifistic twenties. Within his party, MacDonald’s war record was an asset, a testament to his principle and wisdom in the face of irrationality. Yet, his second minority government from June 1929 failed in the face of the Great Depression. In August 1931 MacDonald and a very few colleagues broke with the Labour Party; he led a cross-party, anti-Labour coalition that almost eliminated Labour from the Commons in the subsequent election. For the second time, MacDonald was reviled as a traitor, this time from the left. He continued as prime minister until June 1935. His response to the deteriorating situation in Europe was inevitably shaped by his understanding of how Europe had descended into war in 1914. When he died on 9 November 1937, an enduring hostility from the left coloured his reputation for many years. Neither Labour sympathisers nor his later Conservative associates wished to recall the ambiguous heroism of 1914-18.

David Howell, University of York

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Selected Bibliography

- Elton, Godfrey Elton: The life of James Ramsay Macdonald, 1866-1919, London 1939: Collins.

- Hamilton, Mary Agnes: The man of tomorrow. J. Ramsay MacDonald, London 1923: L. Parsons.

- Howell, David: MacDonald's party. Labour identities and crisis, 1922-1931, Oxford 2002: Oxford University Press.

- Marquand, David: Ramsay MacDonald, London 1977: J. Cape.

- Newitt, Ned: A people's history of Leicester. A pictorial history of working class life and politics, Derby 2008: Breedon Books.

- Tanner, Duncan: Political change and the Labour Party, 1900-1918, Cambridge 1990: Cambridge University Press.