Background and Early Career↑

Born in 1870, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964) was the scion of a traditional Prussian aristocratic officer family. He was an ambitious and capable officer with courage, sangfroid, good health, and the physical stamina necessary to withstand the exhausting campaign in tropical Africa during the First World War. His early career displayed all the ingredients for a potentially rapid rise through the officer ranks in Wilhelmine Germany. He attended the Prussian cadet corps before joining one of the prestigious infantry guard regiments in Berlin. In 1895 he passed the entry exam for the Kriegsakademie (War Academy), a prerequisite for a career on the Prussian General Staff.

Lettow-Vorbeck joined the Prussian General Staff on probation in 1898. In the summer of 1900, Lettow-Vorbeck volunteered for the Ostasiatisches Expeditionskorps (German East Asian Expedition Corps), which was part of the eight-nation coalition formed to suppress the so-called Boxer Uprising in China. During the Herero and Nama Wars in German South West Africa, he began as an adjutant to the commander-in-chief of the German forces, Lothar von Trotha (1848–1920), in 1904–1905. After von Trotha’s disgrace due to his brutal treatment of the defeated Herero, Lettow-Vorbeck made his name as a successful frontline officer in charge of a company of mounted infantry against the Nama. His tours in China and German South West Africa qualified him to command the 2. Seebataillon (Second Sea Battalion) in Wilhelmshaven, one of the three German marine battalions, which also served as reinforcements for the colonies in times of emergency.

Military Campaign in Africa during the First World War↑

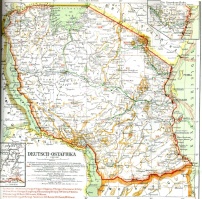

In January 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck, having recently been promoted to lieutenant colonel, arrived in German East Africa to take over the command of the Schutztruppe (Protective Force), a military unit of approximately 2,500 African soldiers, or askari, and 250 German officers, doctors, and non-commissioned officers. Lettow-Vorbeck wanted to use this unit in the event of a European war to attack neighboring British East Africa, thus forcing the British Empire to redirect forces from the European theatres of war to East Africa. Helped by the successful defence of Tanga against a far superior British-Indian expeditionary force in early November 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck managed to sideline his nominal superior, Governor Heinrich Schnee (1871–1949). The colonial administration, as well as the settlers, had initially hoped for the neutralisation of the colony in the event of a war between Britain and Germany. But Lettow-Vorbeck’s finesse in Tanga helped win over the sceptics among the officer corps and the German settlers for his offensive strategy against the neighbouring Entente colonies.

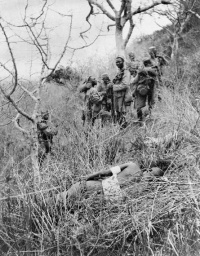

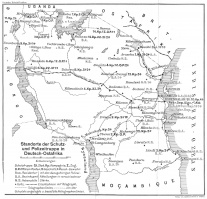

Owing to the weapons captured at Tanga and the mobilisation of settlers and two blockade runners that arrived from Germany, Lettow-Vorbeck's Schutztruppe peaked with about 12,000 askari and 3,000 Europeans in the spring of 1916, supported by tens of thousands of Africans carrying the supplies. By then, he had been promoted to colonel. When British, South African, Belgian, and Rhodesian forces began a combined offensive against the German colony in 1916, he initially fought entrenched battles in the north of the colony. Eventually, however, he was forced to retreat into the less accessible southeastern part of German East Africa. There, for many months, the lack of infrastructure, rainy season, poor health, and supply problems made the situation of the Entente troops very difficult and thus protected the Schutztruppe from likely annihilation by superior enemy forces.

When the Entente forces resumed their offensive in summer 1917 and the situation of the Schutztruppe finally became desperate, Lettow-Vorbeck, who had no instructions from and hardly any communication with Germany, decided not to make a last stand in German East Africa. Instead, in late November 1917 he - by now promoted to Major General - ordered the invasion of the poorly defended Portuguese East Africa with the healthiest and most battle-hardened of his remaining soldiers. This relatively small mobile force of approximately 2,000 soldiers would be able to live off the land and still constitute a permanent threat to the enemy colonies. The last year of the East African campaign thus saw little fighting, but endless marches of the Schutztruppe, pursued by the British, Portuguese, and Rhodesian troops, who were never able to catch it. The Schutztruppe left a trail of scorched earth as it marched through several thousand kilometres of Portuguese East Africa, the southwestern part of German East Africa, and finally North Rhodesia, which it invaded in October 1918. It also took a devastating human toll, which resulted from the forcible recruitment of African carriers and the deprivation of African civilian populations of food. On 25 November 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered with the last 150 or so Europeans and 1,100 askari soldiers, several hundred askari wives and children, and some 1,000 carriers in Abercorn, Northern Rhodesia (today Mbala, Zambia).

Life after the War↑

When Lettow-Vorbeck returned in early March 1919 to Germany, he was celebrated as an undefeated war hero and received many honours over the following years. Owing to his participation in the failed right-wing Kapp-Lüttwitz military coup of March 1920 against the Weimar Republic, he had to take early retirement from the army. He welcomed the Nazi seizure of power, assuming wrongly that it would be the first step for the restoration of monarchy in Germany and the recreation of a German colonial empire in Africa. Even though he was promoted to the rank of full general at the outbreak of the Second World War, he saw no active service in this conflict. Lettow-Vorbeck remained a popular and public figure in the Federal Republic until his death in 1964, not least because of his prestige among his former Entente adversaries, who revered him both as a gifted tactician and as a chivalrous officer. Until the early 21st century, several Bundeswehr barracks carried his name and a few West German towns still have a street named after him.

Legacy↑

Owing to his long and determined resistance in East Africa against far superior enemy forces, Lettow-Vorbeck has occasionally been hailed in Anglo-Saxon historiography as one of the great guerrilla leaders in military history. He was certainly a gifted tactician in mobile warfare who, in the last phase of the war, avoided entrenched battles and preferred instead to outmaneuver and evade the enemy forces. However, his military thinking was mainly forged by the officer training he had received in the Prussian army, which focused on conventional warfare in Europe and defined war only in military terms. Throughout the war his Schutztruppe therefore remained a regular military force, identifiable by its uniforms. It was also known for strictly maintaining the existing racial boundaries between African soldiers and European leaders, as well as the established hierarchies of rank among the mobilized Germans. Lettow-Vorbeck did not call for a levée en masse of the African population to defend German East Africa, nor did he incite Africans to rebel against Portuguese, Belgian, or British colonizers.

Even though Lettow-Vorbeck managed to escape defeat for more than four years, his initial strategic aim for the campaign in East Africa, to force Britain to redirect troops from Europe and thus to help Germany on her European fronts, remained unfulfilled. To combat the Schutztruppe, the Entente powers only mobilized troops that were deemed unfit for service in Europe, or troops that were recruited in Africa after the outbreak of hostilities. Their only mandate was to fight Lettow-Vorbeck. The price the East African civilian population paid for Lettow-Vorbeck’s strategic miscalculation in terms of lost lives, injury, famine, and destroyed property was immense.

Eckard Michels, Birkbeck College London

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Selected Bibliography

- Anderson, Ross: The forgotten front. The East African campaign, 1914-1918, Stroud 2004: Tempus.

- Michels, Eckard: 'Der Held von Deutsch-Ostafrika'. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. Ein preußischer Kolonialoffizier, Paderborn 2008: Schöningh.

- Michels, Eckard: Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, in: Zimmerer, Jürgen (ed.): Kein Platz an der Sonne. Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, Frankfurt a. M. 2013: Campus, pp. 373-386.

- Paice, Edward: Tip and run. The untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa, London 2007: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Schulte-Varendorff, Uwe: Kolonialheld für Kaiser und Führer. General Lettow-Vorbeck - Mythos und Wirklichkeit, Berlin 2006: Links.