Introduction↑

The beginning of the First World War hit the German film industry largely un-prepared. Almost the entire industry was very insecure in the first days of the outbreak of war. After the early victories in the west, the mood within the German Empire transformed from pessimism to patriotic enthusiasm. Many movie theater owners joined spontaneously in the "Deutscher Filmbund", and pledged to withdraw all French and English films from the German repertoire. At the same time war-related partitioning of borders, and the cessation of international trade prevented Germans from engaging with the international film industry almost entirely for a period of ten years.

Coverage of the War Newsreels↑

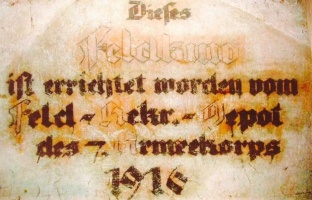

Already in August 1914, the first films depicting mobilization scenes came into the cinemas. These films aroused great rejoicing from audiences, and confirmed the assumption of film producers that future war pictures would attract special public interest. In addition to illustrations showing mobilization, newly copied footage showed images from the belligerent countries, and presented various opinions on the strategic questions, for which military decision were anticipated. Many of these movies were banned shortly after their release because of fears over suspected espionage. The legal basis for this ban involved the adopted laws governing the state of siege in the early war period. Twenty-four military commanders of the army corps areas, and thirty-three governors and fortress commanders took over executive power within their assigned territories. In contrast to press releases, which were heavily regulated, uniform rules were lacking for picture censorship. Therefore, each of the commanders issued his own censorship in his own area of responsibility. For the duration of the war, the newly enacted censors also banned films already approved for production, because they were seen as inappropriate for the war. The decentralization of censorship in this period prevented the emergence of a unified German film market during the war.[1]

On 2 September 1914, EIKO-Film was the first German film company to receive official permission to shoot war scenes. Nevertheless, police in Berlin confiscated EIKO-film’s first war movies on 12 September 1914 for fear of espionage. In some other parts of the country, this type of confiscation had already occurred. The first war newsreels came to the cinemas in October 1914. However, because more images of the war were not allowed to be shown in the first months of the war, theater operators constantly complained about the lack of recent war movies. Film viewings were also limited because many theater operators were engaged in military service in the occupied territories. These limitations coupled with the above-mentioned censorship continued to decrease the prevalence of war cinematography in the following period.

Developed film material had to pass through military censors as well as the respective police censorship in the home territory. Original front recordings were hardly allowed for fear of espionage. The heavy casualties that were occurring during this time were reduced to representations of individual war graves on the big screen. Seriously wounded soldiers were not depicted, and soldiers were only shown wearing bandages, and on the road to recovery. It was not permitted to show modern weapons or naval ports. In the first two years of the war even military leaders refused to be filmed.[2] The German public was thus deprived of seeing real fighting as well as important events, and in fact most of the footage lacked any real relevance. The mounted images contained in these films were not sequentially related, and the viewers were unable to draw logical relationships between them. Temporal sequences of events were not visible, because the principles used to determine the succession of the images were largely arbitrary. In this way, the pictures concealed more than they revealed. The image deficit was filled in many war newsreels by text placed in between the sequences. In order to meet the demand for war cinematography, filmmakers operating under these wartime conditions, had to resort to these clichéd verbal interludes to supplement their footage. The resulting depictions of the way encouraged the widespread perception that the way was unfolding as a "clean and orderly war."

The use of so many clichés came as a result of the course of the war. By 1915, the soldiers had dug themselves into trenches. This technique determined the specific way the soldiers fought. In the trenches, the enemy was invisible. Perception was reduced to what was audible. The few images that were captured were mostly shot in the outback, and re-enacted to simulate images of front lines. The resulting images often showed motionless soldiers under low light conditions.

After the outbreak of war, the then prevalent French newsreels were prohibited, and the newsreels produced by EIKO-Film, along with other German companies, filled the resulting vacuum. Six different newsreels started in German cinemas after September 1914, however, little is known about them.[3] Only the EIKO-WOCHE and MESSTER-WOCHE continued to operate until the war ended.

An analysis of the war newsreels is hampered by the lack of complete editions. The existing single subjects are preserved only in compilations made later, and so detached from their original contexts. Today only the trade press provides an overview. In the early period, the trade press shows a significant discrepancy between the topicality and authenticity of the subject matter alleged by the producers, and the actual images shown on the screen. Even the titles of many films revealed that the hostilities they were depicting were long over at the time the films were shown. Based on a cursory analysis of the subject lists of the films being shown in this period, (which incidentally were not always published completely by the producers in their ads from this period), some substantial tendencies emerge for the first half of the war. Thematically, events of the war dominated the newsreels. Reports from the western and eastern fronts occurred at a comparable level the film releases from MESSTER-WOCHE and EIKO-WOCHE. Films about the Alpine front and naval warfare were less frequent. Images showing the care of wounded soldiers were infrequent, even though they were seen with some regularity in the following years.

In 1916, promotional ads for both of these newsreels dropped noticeably. Advertising instead began to focus particularly on the relationship between the film companies and the political leadership. The tendency for pure image advertising increased further in 1917. EIKO-WOCHE almost completely stopped their promotional activity in the journal "Cinematograph”. Proud reference to the actuality of the reporting remained completely absent. In advertisements for the MESSTER-WOCHE in 1917, reference was made to the current war events only three times. The only coverage referencing the war front discussed the signaled beholdeness of the imperial family with the troops in the field. Even arguments for authenticity did not seem very alluring. Explicit references to the dangerous situation under enemy fire were omitted from these advertisements.

The few newsreels that occurred up until April 1918 refer almost exclusively to representing members of the imperial family. In the last months of the war, advertising for the newsreels stopped completely. After the end of the war, there was no newsreel advertising, with the exception of one announcement on the 25 December 1918.[4] This announcement contained no substantial evidence of content about the end of the Empire, and the changed political situation in Germany. Instead, the ads refer to the future, with both companies seeming to want to continue issuing more positive reports.[5]

The propaganda effect of the war newsreels was low. Responsible reporting that was founded on authenticity and actuality during the early months of the war disappeared relatively quickly from the ads. It is assumed that the audience increasingly distrusted the war newsreels. In this context, it is important to understand how newsreels soon began to gain attention through the use of "patriotic" emotion. Films were produced to encourage a connection between the film-goers and their empire and its leadership. This was done by including graphical representations in the films, and by involving state nobility in the films. It was believed that, given that it was impossible for the film industry to deliver good news from the front, films should be used instead to encourage faith in the government and military leadership.

German Feature Film Production during the War↑

As a replacement for the footage lacking from the various fronts, so-called "enacted war films" were produced. Even before the war, patriotic films, like the movies Theodor Körner (1912) and Bismarck (1913), were met with enthusiasm in German cinemas. Movies set in the military milieu had always found an appreciative audience in the German Empire. When they were still available, they were partly updated and reused at the outbreak of war.

Very quickly, towards the end August 1914, German film producers began to promote their own "patriotic war programs." In these films, scenes were enacted depicting historically shaped ideas related to war, and these scenes were often reinterpreted as “real”, or historically accurate, war scenes. War dramas depicted in cinema, theater, and novels from early in the war, portrayed the Great War using images from the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). These depictions fulfilled all of the classical criteria of relevant communication, and thus secured a temporary economic success. In the beginning of 1915, many other films were produced, on a variety of other subjects. In all of these films, the war appears as a test, through which, by succeeding, the protagonist eventually reaches his proper destination. The interpretation of the meaning of the films was exaggerated in the minds of the viewers, and the atmosphere of the cinema was transformed into a space of bourgeois cultural sentimentality.[6]

By the end of July 1914, there was an oversupply of movies on the German market. However, with the outbreak of war, the introduction of censorship decrees, the temporary ban on films produced in the enemy states, quickly led to an acute lack of feature films. Thus, the demand for German films grew. The result, especially in the capital, was a rapid increase in new film companies. At this time, the Berlin film industry continued to expand, consolidate and hold its dominant position as a film production location until the end of the Second World War.

From the middle of 1915, movie theaters were dominated by German films, most of which were named after the main cast member. Despite many serial productions, German producers failed to satisfy the approximate demand for films up until 1918.

From the middle of 1915, detective films and film series from German production companies dominated the cinemas. Even despite serial productions in other genres, German producers continued to fail to meet demands. As a result of legal and censorship restrictions, British and French films acquired before the war dominated most German cinemas in 1915, until they were banned. After this time, cinema operators continued to seek films that were produced in the neutral countries. The film company Nordic, a subsidiary of Nordisk Film Company in Copenhagen, benefited most from this development. It grew in a very short time to become the main competitor with the German producers.[7]

Film as a Propaganda Tool↑

The First World War was the first media war. According to the German government, there was only one source of official propaganda for the first half of the war. In view of the inconclusive attrition-style of warfare, by 1916, the meaning of the war became increasingly questionable in the minds of the German population. Growing war-weariness existed in contrast to the concept of total mobilization propagated by the Third Supreme Army Command (III OHL). Those advocating for total mobilization believed that they might be able to combat war-weariness through more intensive propaganda work at home and abroad. In this context, a re-evaluation of the film industry began, and initial design considerations began for the post-war period. It was believed that through the use of all forms of media, people in foreign countries, as well as in Germany, could be convinced of German superiority.[8] Convinced that the direct effect of the images contained in films was especially potent, proponents of German propaganda bestowed upon the film the ability to convince viewers of a reality that was in line with the war-time goals of the German Empire, and assumed that films would be able to influence the thought patterns of their recipients in favor of German war success. The bourgeois cinema commentators had criticized the lack of intellectual vigor and the high levels of emotion in German films produced up until the second half of the war. However, in the latter half of the war, the chance to express feelings through film was interpreted as an advantage. This paradigm shift, owing much to the course of the war, opened up a new thematic and representational space. In contrast to the war films produced during the early phases of the war, that were similar to those of the other belligerent nations, the feature films shot in the aftermath of the war formed the basis of a more professional type of film production, and thus the expression of a national film culture in the post-war period.

This new orientation, which included the withdrawing of particularly rigid censorship rules, was taken up primarily by three new companies, including The Military Film and Photo Office (Militärische Film- und Photostellen), which emerged later in the Picture and Movie Office (BuFA), the German Cinema Society (Deutsche Lichtspiel Gesellschaft, or DLG) and the Universum Film AG (UFA). Convinced of the great effect of film, all three companies tried to occupy short and long term positions in the market at home and abroad. This strategy continued beyond the end of the war.[9] The top leadership of DLG and UFA believed that this objective could be achieved only if their companies were economically viable. There were considerable similarities in the objectives of DLG, BuFA and UFA. The actions of these three companies reinforce the argument that in the film industry, as well as in business circles and the military and government, a specific attempt was made in the second half of the war to develop industry structures during wartime.

Even before the war began, there were discussions within the German film industry to use film to advance their own industry interests. At the beginning of the war, these long-term objectives were temporarily abandoned. However, as the war continued, which lead to a loss of markets, leading industrialists pushed throughout the second half of the war to start their own film companies. Their objectives were to produce promotional films advertising German products at home and abroad. The development of these new film companies coincided with an increase in the influence of the daily press and the advertisement industry. For example, Alfred Hugenberg (1865-1951), an influential politician and business-man during this period, was successful in securing the decisive influence of heavy industry on the proposed company (DLG), and thus on the movie content it produced. The founding of the DLG in 1916 was the first institutional expression of the reorientation of the film industry by leading forces of the Empire. Since the commercials alone were not useable, they were integrated into complete programs of short films.[10] Because there was a chronic shortage of short films in German cinemas, it was hoped that the inclusion of these excerpts would attract audiences. By means of cooperation with government bodies, and through collaboration with film industries located in neutral and friendly foreign countries, foreign audiences were also exposed to these same films.

The German General Staff and the government took as a first step in their active propaganda activities, the production of war films that would strengthen the will of the German population for war, and would convince foreigners of the invincibility of German guns. To this end, the Military Film and Photo Offices were established in the Foreign Office in 1916. In these offices, soldiers and officers were active in producing images on the front. As the war continued, the film images were perceived to be increasingly less novel, and interest in these films began to decrease. Several ministries of the federal states came together to found the BuFA in early 1917, with the support of the Foreign Office. To ensure the procurement of images from the fronts, the mobile film troops of the former Military Movie Film and Photo Office were made available. In the course of a year, their numbers were increased from seven to nine. To ensure that the various audiences would accept these new war films, they were embedded in complete cinema programs, sold by BuFA at home and abroad, as well as on the front. In addition to the official war films, these programs contained films made by private companies, including game films, dramas, cartoons, animated films and films about nature photography, among other genres. The lack of spectator interest in war images, and in some other film genres was offset by the fact that they were distributed nationwide, increasing viewership. In the last months of the war, however, they disappeared almost completely from German and foreign cinemas.

The lack of success achieved by the DLG and BuFA programs in the cinemas was immediately clear. One issue was the lack of diversity in the film industry, both with regards to the small number of firms and the limited types of films productions. Audiences were receptive to many of these films, only because they were exposed to them. Furthermore, there were no proprietary distribution and marketing structures, and almost no movie theaters, where these film programs could be evaluated. The film distributions had signed long-term contracts with distributors, so that they had no opportunity to show BuFA and DLG programs. Meanwhile, long-term changes to film industry occurred primarily in the international film market. While the DLG and BuFA concentrated on the production of short films, feature length movies became increasingly popular during the course of the war, especially in the better-equipped movie theaters at home and abroad. For film producers, first-copy costs increased, and at the same time, the risk that a film could fail for lack of spectator interest at the box office also increased. All of these deficits could only be countered by substantial financial investment in all three segments of the film industry, and through a financially strong film rental market abroad.

Founding the UFA↑

As the war dragged on, there was an increased demand for fictional films. Long format, and specifically feature-length films, aimed their content and aesthetics more towards the bourgeoisie, who as a class, had largely rejected the idea of the cinema up until this time.[11] Around 1916, there was mounting pressure on the film industry to abandon the government supported, one-sided representation of war images in films. At the same time, there was a growing fear in many German government ministries that the influence that German heavy industry had on the film market was getting to be too strong. There was also fear within the German film industry itself that the influence excerpted by Nordisk, the Danish film company aforementioned, was growing too quickly. Nordisk took advantage of the reduced capitalization of the German film industry during the war, and had manage to gain control of cinema operations in over forty German cities by 1917. Nordisk was a strong distributor and could distribute films Europe wide from their operations based in Denmark. Because it was able to operate out of neutral Denmark, the company maintained strong production that did not suffer because of the war. In Germany, in addition to the lack of capital, strict censorship contributed to the lack of international competitiveness achievable for German films. Against this background, the Prussian War Ministry and the Zentralstelle für Auslandsdienst (Central Office of Foreign Service) spoke in the fall of 1916 to the Chancellor, on behalf of establishing a major film company in Germany.[12]

Due to the lack of public interest in BuFA programs, and due to the increased propaganda efforts of the Entente, the Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937) wrote a letter to the Royal Ministry of War on 4 July 1917, at the suggestion, and with the participation of the Chief of Military Intelligence Division of the office of the Foreign Ministry, Hans von Haeften (1905-1944). This letter is regarded as one of the birth certificates of UFA. The letter proposed that: "the war had demonstrated the superior power of images and film as a tool of reconnaissance and means of influence." Therefore Ludendorff demanded increasing the prominence of advertisements in the film medium, for films produced both at home and abroad in other neutral countries. This would allow the domestic film industry to be strengthened, and would prevent Nordisk from dominating the German film market. Ludendorff argued that this effort should be undertaken primary in Russia and Scandinavia, as these were the best locations strategically for Germany to pursue her war-time goals. Therefore, Ludendorff called for the establishment of a major German film company, which would be funded by both the German government, as well as one German bank.

In addition to further proposals from various other government agencies, Ludendorff’s arguments formed the basis for founding UFA. When it was founded in December 1917, UFA had four goals: 1) to increase the efficiency of the German film industry with a particular emphasis on film production, 2) to exclude foreign film companies from the German market in the post-war period, 3) to search for market opportunities for German films abroad and 4) to improve the quality of German feature film programs.

Statements around the time of the founding of UFA show that only a limited value was granted to the entertainment value of a film movie at this time. The administration wanted the audience to be interested in the mass appeal of entertainment films, but only so that films could be used to reinforce the goal of permanently teaching and influencing the cinema-going audience. For this reason, shorter promotional, educational films and newsreels were selected for presentation over and above movies. It was decided that the intended goals of UFA would only be achieved when the companies being established gained a decisive influence on all three branches of the film industry, as well as of film rental markets in foreign countries. This preferred position would be permanently guaranteed by the introduction of a uniform film censorship body, and through the general regulation of films, in the form of a concession law discussed in the Reichstag parliament in 1917 and 1918. With respect to foreign countries, another goal of UFA was the creation of a "Central European film block" under German leadership. This block would help in keeping foreign films away from the local market, as well as neighboring states, therefore ensuring that German films would bring financial returns.[13]

For reasons of secrecy, in the summer of 1917 the Chancellor commissioned the Prussian Ministry of War with the responsibility of concretely implementing UFA. After long negotiations between government offices, the War Department, representatives from several branches of industry and banks, as well as selected representatives of the film industry, UFA was officially founded on 18 December 1917, with a registered capital of 25 million marks. To ensure that the war interests of the Empire (who contributed 8 million Reichsmark UFA’s founding) were upheld, additional funding was supplied by a control group of banks and several large business enterprises that together invested another 6.4 million Reichsmark. The three largest existing film companies in Germany, Nordisk Film AG, the Messter Film, and the PAGU, were bought and incorporated into UFA.[14] This ensured that UFA was able to act independently from the start in all three sectors of the film industry. The founding of a foreign movie rental department and a cultural department, along with the purchase of cinemas and film companies at home and abroad, advanced the scope of the company before the end of the war.

The holding’s structure of UFA guaranteed that the film company would be able to carry through on its initial film projects, without interruption. UFA’s leadership sponsored the production of many feature films that were internationally attractive. It was hoped that these films would increase the acceptance and sales of other German products abroad. In the cultural film department, the first films with exclusively civilian content were produced, as part of the movie theater reform movement of 1918. War films were no longer produced by UFA up until the end of the war.

Cinematic representations of World War I in the Weimar Republic↑

Cinematic reflections of the Weimar Republic during the First World War can be categorized into a distinction between two different approaches. Some films addressed the military in general, while others referred directly to the war itself. It should be noted that throughout the first half of the 1920s military topics were off-limits to a great extent in the Weimar Cinema, with the exception of some short films. In 1924 and 1925 a few American motion pictures withplots that were set in the context of the Great War, also constituted exceptions to this general rule.[15] The motion picture Rosenmontag from 1924 (reperformed as sound film in 1930), which generally criticized conditions in Prussia and Germany during the war, was another exception.

Throughout the second half of the Weimar Republic, several more films were released on the subject of war, however, the overall number still remained small relative to the total number of films released by UFA. In 1927, UFA screened the first part of a compilation film with partial undisclosed images from the World War. This film did not succeed at the box office. A follow-up to this film, which was already in production, was completed, but a planned for third part was never completed. Further films reconstructed single wartime events in the style of New Objectivity with the professional support of former officers and source documents, as well as embedded plots and animated cartoons. For example, Unser Emden (1926, reperformed as sound film in 1932), Richthofen, der rote Ritter der Luft (1927), Die Somme (1930) and Tannenberg (1932).

After the middle of the 1920s until 1933, several military humoresques emerged in accordance with the older tradition of depicting military farces in the German Empire which extensively privatized the war and the military. The same applied to spy films like Leichte Kavallerie (1927), Im Geheimdienst (1931) and Die unsichtbare Front (1932). Simultaneously, motion pictures emerged that criticized conditions in imperial Germany generally, and also criticized the War itself. For example, Das edle Blut (1927), Kadetten (1931), Westfront 1918 (1930) and Niemandsland (1931).[16] In 1914, the director of Die letzten Tage vor dem Weltenbrand (1930), tried to depict people from contemporary history – some of which were still alive at the time of the films release – in the direct run-up to war.[17]

The last war picture produced in the Weimar Republic, Morgenrot (1932/33), premiered in Berlin on 2 February 1933. Among others, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and the ministers of the new government, Franz von Papen (1879-1969) and Alfred Hugenberg – UFA's chairman of the supervisory board – sat in the auditorium. In contrast to the war films shot in the Nazi era, this film thematized not only heroism, but also the sorrow of relatives.

Conclusion↑

At the beginning of the war, there was no concept of propaganda on the German side. For them, film was considered as a cheap means of entertainment without any other meaning or purpose. In 1915 and 1916, this view changed. The Entente Powers, and later the Americans, used film to promote their vision of war. As the war dragged on, war weariness increased in Germany and abroad. This lead some Germans to reconsider the role of film. On the one hand, the film industry tried to use film for the specific goal of improving the mood of the population, and on the other hand, they established, through the founding of the DLG and the UFA, the economic structures (closely intertwined with government and industry) that would support the film industry in the post-war era

Wolfgang Mühl-Benninghaus, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Section Editor: Christoph Cornelißen

Notes

- ↑ Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Vom Augusterlebnis zur Ufa-Gründung. Der deutsche Film im Ersten Weltkrieg, Berlin 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Jung, Uli/Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Front und Heimatbilder im Ersten Weltkrieg, 1914-1918, in: Jung, Uli/Loiperdinger, Martin (eds): Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland, vol. 1: Kaiserreich 1895-1918, Stuttgart 2005, p. 393.

- ↑ Giese, Hans Joachim: Die Film-Wochenschau im Dienste der Politik (Leipziger Beiträge zur Erforschung der Publizistik vol. 5), Dresden 1940, p. 39.

- ↑ Annonce, in: Der Kinematograph, No. 625, 25 December 1918.

- ↑ Jung/Mühl-Benninghaus, Front und Heimatbilder 2005, p. 397.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 390.

- ↑ Mühl-Benninghaus, Vom Augusterlebnis 2004, p. 272.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich: Kriegserinnerungen, 1914-1918, Berlin 1918, p. 2.

- ↑ Annonce der DLG, in: Der Kinematograph, No. 544, 30 May 1917.

- ↑ Barkhausen, Hans: Filmpropaganda für Deutschland im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Hildesheim et al. 1982, p. 85.

- ↑ Mühl-Benninghaus, Vom Augusterlebnis 2004, p. 272 ff.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv, BA R 901 ZfA Nr. 947 Bl. 34 ff.

- ↑ BA R 901 ZfA/ 974 Bl. 3

- ↑ BA R 8119/ 19103 Bl. 149

- ↑ Saunders, Tom: Politics. The cinema, and early revisitations of war in Weimar Germany, in: Canadian Journal of History 23 (1988), p. 25.

- ↑ Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Der Erste Weltkrieg in den Medien zur Zeit der Weltwirtschaftskrise, in: Heukenkamp, Ursula (ed.): Militärische und zivile Mentalität. Ein literaturkritischer Report, Berlin 1991, p. 122.

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 107.

Selected Bibliography

- Barkhausen, Hans: Filmpropaganda für Deutschland im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Hildesheim; New York 1982: Olms Presse.

- Bub, Gertraude: Der deutsche Film im Weltkrieg und sein publizistischer Einsatz, Quakenbrück 1938: Trute.

- Dibbets, Karel / Hogenkamp, Bert (eds.): Film and the First World War, Amsterdam 1995: Amsterdam University Press.

- Giese, Hans Joachim: Die Film-Wochenschau im Dienste der Politik, volume 5, Dresden 1940: M. Dittert.

- Huth, Lutz / Krzeminski, Michael: Staatliche und private PR-Aktionen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die Herausbildung einer neuen Kommunikationsform: Professionalität der Kommunikation. Medienberufe zwischen Auftrag und Autonomie; Lutz Huth zum 60. Geburtstag, Cologne 2002: Halem.

- Kreimeier, Klaus: Die Ufa-Story. Geschichte eines Filmkonzerns, Munich 1992: C. Hanser.

- Lefranc, Herrmann: Die Filmindustrie, thesis, Heidelberg 1922.

- Ludendorff, Erich: Meine Kriegserinnerungen, 1914-1918. Mit zahlreichen Skizzen und Plänen, Berlin 1919: E.S. Mittler und Sohn.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Der Erste Weltkrieg in den Medien zur Zeit der Weltwirtschaftskrise, in: Heukenkamp, Ursula (ed.): Militärische und zivile Mentalität. Ein literaturkritischer Report, Berlin 1991: Aufbau Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: 1914. Die letzten Tage vor dem Weltenbrand, in: Belach, Helga / Jacobsen, Wolfgang (eds.): Richard Oswald. Regisseur und Produzent, Munich 1990: Text + Kritik, pp. 107-112.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Vom Augusterlebnis zur Ufa-Gründung. Der deutsche Film im 1. Weltkrieg, Berlin 2004: Avinus-Verlag.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Newsreel images of the military and war, 1914-1918, in: Elsaesser, Thomas / Wedel, Michael (eds.): A second life. German cinema's first decades, Amsterdam 1996: Amsterdam University Press.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang / Jung, Uli: Front und Heimatbilder im Ersten Weltkrieg (1914-1918), in: Zimmermann, Peter / Jung, Uli / Loiperdinger, Martin (eds.): Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Kaiserreich, 1895-1918, volume 1, volume 1, Stuttgart 2005: Reclam, pp. 381-486.

- Müller, Corinna / Segeberg, Harro: Die Modellierung des Kinofilms. Zur Geschichte des Kinoprogramms zwischen Kurzfilm und Langfilm, 1905/06-1918. Mediengeschichte des Films, volume 2, Munich 1998: W. Fink.

- Rother, Rainer (ed.): Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Bilder des Ersten Weltkrieges, Berlin 1994: Das Historische Museum: Ars Nicolai.

- Saunders, Tom: The cinema, and early revisitations of war in Weimar Germany, in: Canadian Journal of History 23, April 1988.