Introduction↑

Aleksei Alekseevich Brusilov’s (1853-1926) military and political activity has its defenders and critics among historians. One faction sees the general as an outstanding military leader in the First World War, responsible for the Russian army’s greatest victory in this period: the breakthrough at Lutsk, which was later deservedly named the Brusilov Offensive after him. He adopted the most up-to-date strategic and tactical methods, many of which remained in wide use during the Second World War.

His critics question how outstanding he was, with some even describing him as a mediocre general. They say his name is undeservedly connected to the breakthrough at Lutsk: several military commanders, not just Brusilov, prepared and implemented the successful operation. In addition, Brusilov chose not to join the White movement and oppose the Bolsheviks; he even signed up to the Worker and Peasants’ Red Army, thereby helping the Soviet regime.

Background↑

Aleksei Brusilov was born to a noble family (his father attained the rank of general) and raised in the Russian Orthodox faith. He underwent military training in the Page Corps (1872) and started his military career in 1872 as an ensign in the 15th Tver Dragoon Regiment, where he served as an adjutant. Brusilov fought in the Caucasian theatre of the Russo-Turkish War, from 1877 to 1878. He distinguished himself during the capture of the Turkish fortresses of Ardahan and Kars. Between 1878 and 1881, he headed the regimental training detachment. From 1883, he served on the staff of the Cavalry Officer School in various posts: as an adjutant, assistant commandant, head of the riding school and head of the dragoon section. He was an active participant in cavalry races. In 1902, having been promoted to major general the previous year, he became the commandant of the Cavalry Officer School. In 1906, he was awarded the rank of lieutenant general and was appointed head of the 2nd Guards Cavalry Division. In 1909, he was named commander of the 14th Army Corps and in 1912 assistant commander of the forces in the Warsaw Military District. He became general of the cavalry, the highest rank of general, in 1912.

First World War↑

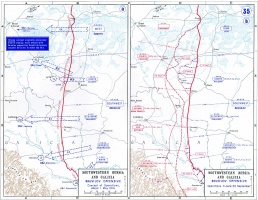

On the eve of the First World War, he commanded the 12th Army Corps. After mobilisation was declared, he was named commander of the Proskurov army group, which was soon reformed as the 8th Army and fought well during the Battle of Galicia. Consequently, he was awarded the Order of St. George, 4th and 3rd Class (23 August and 18 September 1914) and the St. George Sword (27 October 1915). In March 1916, he became commander-in-chief of the south-western front. His forces undertook a major attack on the Austro-Hungarian lines between May and August 1916, which became known as the breakthrough at Lutsk. Later, Soviet historiography named it the Brusilov Offensive. A number of features distinguish the attack: the artillery bombardment over several hours, the advance toward enemy positions at night and the attack against multiple points rather than just one. For the breakthrough, Brusilov received the George Sword with Diamonds on 20 July 1916.

Post-war Career↑

In November 1917, Brusilov welcomed the fall of the Romanov dynasty and the Provisional Government’s accession to power. He advocated the creation of shock and revolutionary units to raise the army’s morale. In May 1917, he became commander-in-chief. However, after the unsuccessful offensive in Galicia, he was replaced by General Lavr Georgievich Kornilov (1870-1918) in July. He retired and returned to live in his private flat in Moscow. In November 1917, during clashes between units loyal to the staff of the Moscow Military District and detachments of the Red Guard, a shell landed in his home, wounding him in the leg. The Soviet secret police, Cheka, arrested him in August 1918 on suspicion of “counter-revolutionary activity” and placed him under house arrest. In December 1918, all charges against Brusilov were dropped. He joined the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, becoming a member of the Military Historical Commission for the Study and Implementation of the Experience of the War, 1914-1918. At the beginning of the Polish-Soviet War, he proposed creating a Special Commission under the commander-in-chief of the Red Army, made up of professional officers, to organise the struggle against Polish forces effectively. In May 1920, he became chairman of the Special Commission. He twice signed appeals to White officers to join the ranks of the Red Army in order to repulse the external enemy. He was also the initiator of the decree of the Soviet of People’s Commissars of 2 June 1920, “On Former Officers”. This freed officers from Soviet Russian prisons and concentration camps. In June 1920, he became inspector of the Central Administration of Horse Breeding and Animal Husbandry under the Commissariat of Land. On 6 October 1920, he was appointed a member of the Military Legislative Commission under the Revolutionary Military Council. After the abolition of the Special Commission, he entered the Red Army reserve. On 1 February 1923, he became an inspector of cavalry in the Red Army. On 31 March 1924, he was appointed serviceman for special commissions under the Revolutionary Military Council. In spring 1925, he travelled to Czechoslovakia for medical treatment and despite the personal character of his visit, he was welcomed with state honours. He died in Moscow and was buried at the cemetery of the Novodevichy Convent.

Conclusion↑

Brusilov had a brilliant career in the Russian army, becoming one of the most well-known generals in Russia during the First World War. However, during the Russian Revolution, when the army began to disintegrate, he was not able to act effectively and was forced to give up the post of supreme commander-in-chief. Despite joining the Red Army, he maintained his critical view of the Soviet regime.

To the end of his days, the general retained an interest in new military technologies, including chemical weapons and aviation. Despite the fact that Brusilov was considered one of the best cavalry specialists, he believed that in a few years cavalry would lose its military significance, as modern technology would replace it. Brusilov left behind his memoirs. The first part was published in the USSR on several occasions after 1929, albeit with several passages removed. His widow, Nadezhda Vladimirovna Brusilova (1864-1938), gave the manuscript of the second part to the Russian Historical Archive Abroad in Prague in 1932 after emigrating from Russia. According to the general’s widow, Brusilov had written and dictated the second part of his memoirs while receiving medical treatment in Karlovy Vary. The second part contained critical comments about the Soviet regime’s leaders. After the Second World War, when the Prague archive was transferred to the USSR, the Soviet leadership became aware of the second part of Brusilov’s memoirs. For a long time, his name was practically forbidden. During the thaw under Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971), the commander was rehabilitated, to a large degree thanks to the efforts of the Soviet military historian Ivan Ivanovich Rostunov (1919-1993). The second part of the general’s memoirs was first published in the “Military Historical Journal” between 1989 and 1991. Afterwards, the full text appeared in two parts with separate publishers.

There are memorial plaques associated with Brusilov in Ukraine and Russia. His burial memorial is on the grounds of the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow. In the Ukrainian town of Vynnytsia, in December 2006, a bas-relief was erected on a house in the street in which the commander lived with his family in 1916. A bronze statue of the general was unveiled in November 2007 in St. Petersburg (sculptor: Y.Y. Neiman, architect: S.P. Odnovalov). Streets are named in honour of Brusilov in Voronezh and Moscow.

Evgenii Vladimirovich Volkov, South Ural State University

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Translator: Christopher Gilley

Selected Bibliography

- Rostunov, Ivan Ivanovich: General Brusilov, Moscow 1964: Voenizdat.

- Semanov, Sergeĭ Nikolaevich: General Brusilov, Moscow 1988: Voennoe izdatelʹstvo.

- Sokolov, Iu. V.: Krasnaia zvezda ili krest? Zhiznʹ i sudʹba generala Brusilova (A red star or a cross? The life and fate of General Brusilov), Moscow 1994: Rossiia molodaia.