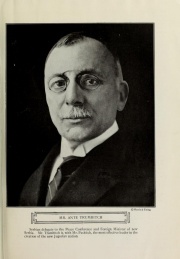

Early Life and Pre-war Career↑

Ante Trumbić (1864-1938) was born in the Dalmatian port of Split, in the Austrian Empire, and went on to study and train as a lawyer in Zagreb, Vienna, and Graz where he completed a doctorate in 1890. An interest in nationalist politics saw him elected to the Dalmatian Diet in 1895 and the Austrian parliament in 1897. From 1903, he became a leading proponent of the “New Course” (Politika novoga kursa). This was a political programme that advocated extensive socioeconomic reforms and political autonomy for the empire’s southern Slavonic territories through the unification of Austrian-administered Dalmatia with Hungarian-ruled Croatia-Slavonia. Coupled with underlying fears of Austrian and Hungarian nationalism, Trumbić’s own Yugoslavist convictions – that perceived Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes as distinctive “tribes” of a single Yugoslav race – provided the New Course’s ideological underpinnings.

Following Trumbić’s election as mayor of Split in 1905, the tenets of the New Course were laid out in the “Rijeka Resolution” (Riječka rezolucija) precipitating the formation of the Croat-Serb Coalition (Hrvatsko-srpska koalicija) by Trumbić, the journalist Frano Supilo (1870-1917), and other pro-Yugoslav personalities. Despite several splits – and the Imperial government’s attempts to discredit it – the Coalition dominated the political landscapes of both Dalmatia and Croatia-Slavonia until 1918.

Wartime Exile and the Yugoslav Committee↑

Against the Coalition’s political successes, Trumbić grew increasingly suspicious of Vienna and Budapest. By 1913, he and Supilo agreed that, should a European conflagration break out, they would work towards dismantling the monarchy’s rule in the Southern Slav territories and seek their unification with Serbia and Montenegro. This was made untenable with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) and Austria-Hungary’s subsequent invasion of Serbia: both politicians were prompted to flee to Italy. Whilst there, they agreed to accept Serbian financial backing to establish a lobby group, the Yugoslav Committee, (Jugoslavenski odbor) that would seek Entente support for the secession of the monarchy’s Southern Slav territories and their post-war unification with Serbia.

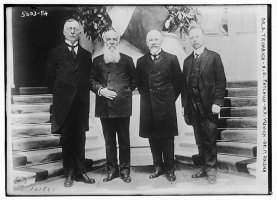

The Yugoslav Committee was founded in Paris in April 1915, but it relocated to London for the duration of the war. Despite establishing contacts in the British and French governments, it lacked political influence and diplomatic recognition. Furthermore, disagreements over its increasingly strained relationship with the Serbian government of Nikola Pašić (1845-1926) led to Frano Supilo’s resignation in June 1916. Of greater concern, however, was the 1915 Treaty of London. In exchange for Italy’s entry into the war against Germany, the treaty promised Rome extensive territorial acquisitions, including most of Dalmatia. Nevertheless, with Supilo’s approval, Trumbić and Pašić formally announced their joint commitment to the creation of a Yugoslav state in the Corfu Declaration of July 1917.

Creation of Yugoslavia and the Paris Peace Conference↑

Following Austria-Hungary’s dissolution in the autumn of 1918 and proclamation of a Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in December, Trumbić became the new country’s first foreign minister. Alongside Pašić he led the Yugoslav delegation at Versailles. Personal animosity towards his Serb counterpart, as well as concerns over Belgrade’s political machinations, created tension within the delegation. However, this was superseded with the threat posed by Italy’s bellicose territorial demands. Through cooperation and skilful diplomacy, Trumbić and Pašić managed to retain most of Dalmatia.

Post-war career↑

Resigning as foreign minister in November 1920, Trumbić was initially elected as an independent in 1921. He voted against the Vidovdan constitution that proposed a unitarist state centred on Belgrade. As the interwar years passed, his disillusionment with the kingdom steadily increased as successive Serb-dominated governments ignored or overruled demands for its federalisation. Furthermore, his political fortunes declined with the introduction of universal male suffrage; his own brand of Liberal-nationalism failed to gain traction against the populist Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska seljačka stranka) under its charismatic leader Stjepan Radić (1871-1928).

Disenchantment turned to enmity following Radić’s assassination in 1928, and the subsequent deceleration of a royal dictatorship by King Aleksandar Karađorđević (1888-1934). In an interview with the Manchester Guardian in September 1932, Trumbić even advanced the idea of the kingdom’s Croat-inhabited territories seceding to pursue a union with Austria. In November, Trumbić, in collaboration with Radić’s successor Vladko Maček (1879-1964), authored the “Zagreb Points” (Zagrebačke punktacije), a resolution demanding the restoration of democracy and an end to Serb hegemony. This period marked a brief revival in Trumbić’s career. Joining the Peasant Party in 1931, his experience secured him a senior position. In 1933, Maček’s arrest, and the assassination of the party’s vice-president Josip Predavec (1884-1933), left Trumbić as both its temporary president and de facto leader of Yugoslavia’s political opposition. His life-long ambition of an autonomous Croatian entity became an, albeit brief, reality following the Cvetković–Maček Agreement (Sporazum Cvetković-Maček) of August 1939, nine months after his death.

Samuel Foster, University of East Anglia

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Boban, Ljubo: Prilozi za biografiju Ante Trumbića u vrijeme šestojanuarskog režima (1929-1935) (Contributions to the biography of Ante Trumbić during the Sixth of January regime (1929-1935)), in: Historijski zbornik (Historical Anthology) 21-22, 1968-1969, pp. 1-74.

- Djokić, Dejan: Nikola Pašić and Ante Trumbić. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, London 2010: Haus Publishing.

- Lampe, John R.: Yugoslavia as history. Twice there was a country (2 ed.), Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Perić, Ivo: Ante Trumbić na dalmatinskom političkom poprištu (Ante Trumbić in the Dalmatian political arena), Split 1984: Muzej grada Splita.