Introduction↑

When Australia went to war in August 1914, its press overwhelmingly supported the Commonwealth’s participation and the decision to enlist a force of 20,000 volunteers for overseas service. This article on the Australian press/media between 1914 and 1918 will discuss how the conservative mainstream newspapers supported successive governments’ vigorous pro-war policies – not through blind adherence to official direction but because they shared the same ideological outlook as the politicians. While Australia maintained a tough censorship regime throughout the conflict, journalists, editors and their proprietors were willing, often enthusiastic, supporters of a cause that did not require compulsion in the first place.

Going to War↑

As the European crisis intensified during July 1914, Australian newspapers, both metropolitan and regional, offered a range of opinions extending from cautious optimism to wondering how Australia might support the mother country in the event of war. Generally, the hope was expressed that, as with earlier crises – over Morocco, for example – diplomacy would prevail and conflict would be avoided.

Thus, on 31 July 1914 the lead editorial in the Sydney Morning Herald stated:

It could not be managed, of course, and within the week Australia had followed Britain into war.

An enduring storyline associated with the Great War’s outbreak is that of popular enthusiasm, even hysteria, for participation in the conflict. Recently, historians have questioned just how sustained and widespread this mood really was. In Australia, as elsewhere, a temporary unity brought together political parties and different sections of the press. When Australia committed an expeditionary force of 20,000 men to serve overseas, mainstream newspapers warmly welcomed this gesture of support for the Empire. For example, the Melbourne Argus argued on 3 August 1914 that "practical assistance should be given will be generally agreed". The same issue of this paper reported on the much-quoted speech by Labor party leader, Andrew Fisher (1862-1928). Here Fisher promised that "Australians will stand beside our own to help and defend her [i.e. Britain] to our last man and our last shilling."[2] It was a prescient statement.

The Australian Press in 1914↑

In 1914 Australia’s press was dominated by its metropolitan morning and evening dailies – the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age and Argus in Melbourne, the Brisbane Courier and so forth. These were often family interests with, for instance, the Fairfax family owning the Sydney Morning Herald and the Syme family controlling the Age from 1856 to 1983. In a large country with underdeveloped communications (such as relatively rudimentary railway links between the states), there were also a significant number of regional publications and a vigorous labor press. There was both extensive cooperation and competition between newspapers in terms of sharing news and cable access, or alternatively keeping rivals out of the loop and attempting to establish monopolies over such things as the crucial international telegraph services. The first cable connection between Britain and Australia was established in 1872 and until 1902 this link held a monopoly on telegraph cable transmission. In that year a new Pacific cable service was established, again linking Australia to Britain and maintaining the web of imperial communications. In 1914 the most important source of foreign news in Australia was the Reuters news agency based in London. Reuters’ significance in the composition of Australian news would only be enhanced during the First World War as demand soared for information about the distant conflict.

Despite the surface unanimity of the mainstream press, not all greeted the advent of war with unbridled enthusiasm. The weekly Bulletin, a champion of Australian nationalism in the 1880s but considerably more conservative by 1914, was rather tepid in the early days of the war when it actually commended the Kaiser for his efforts in sustaining peace for so long.[3] It soon fell into line though – the imposition of a government censor assisted here – and the anti-German cartoons by well-known writer and artist Norman Lindsay (1879-1969) that the Bulletin published during the war were spectacular exercises in visual propaganda. They generally portrayed the Germans as crazed beasts whose malignant intentions directly threatened Australia; giant "Huns" with clubs and talons reached out from afar to molest Australia. Thus the media drove home the message that though the war was happening thousands of miles away, Australians were, in the words of recently defeated Prime Minister Joseph Cook (1860-1947), "fighting for the liberties of Australia, for the social ideals of this home of ours, as well as for the homes of the kingdoms over the sea."[4]

Censorship↑

At the outbreak of war Australia was engaged in a federal election campaign. Not surprisingly, the party leaders competed in patriotic assertions that matched those of the newspaper editorials. The Labor party leader under Andrew Fisher comfortably won the poll on 5 September 1914. With the enthusiastic support of the opposition, the new Labor government then passed the War Precautions Act in unprecedented haste on 28 October 1914, which provided them with wide-ranging powers to extend existing censorship provisions, influence the course of public debate and suppress any potential or actual dissent. After the war, Official Historian Ernest Scott (1867-1939) provided a brief but sweeping panorama of similar measures reaching back to the time of Napoleon to justify the scope of this legislation and the imposition of censorship in Australia, which he described as one of the "unfortunate necessities of warfare."[5] What Scott failed to do was critically examine the haste with which Australia’s parliamentarians rushed a quickly drafted act through two houses of parliament and towards royal assent without a murmur of doubt and in the shortest time possible. Open debate on the merits and conduct of the war was discouraged, yet the situation should not be exaggerated. As Niall Ferguson noted, "[in] no country was the press completely restricted, nor was uniformity ever imposed. In every case, institutions for censoring and managing news had to be improvised and did not work efficiently."[6] This was true of Australia as well, where censorship was often maladroit but never total. It was tolerated by the mainstream press, though even the Argus, as conservative a journal as any in Australia, disliked its purely political aspect.

Outright condemnation of the war in Australia was restricted to smaller scale left-wing or union publications. One such organ was The Labor Call, which greeted the war as something "worked up by a few crowned-heads of Europe, assisted, no doubt by trusts and combines."[7] Another was the Australian Worker, which on 1 October 1914 attributed the war to "military ambition, trade rivalry, high finance, the desire for territorial expansion and the lust for gold."[8]The Labor Call was scarcely read at breakfast in every Australian household, nor was the Australian Worker, but their significance – and that of other "specialist" publications such as the Advocate, which represented Catholic AND Irish opinion in Melbourne – should not be overlooked. When fissures appeared in Australia, such as occurred over conscription between 1916 and 1917, smaller journals could tap into the feelings of particular groups, whether politically or religiously based, and help concentrate people’s energies into opposing government-sponsored measures. But in the heady days of 1914 divisions of any sort in the new Commonwealth appeared to have been smoothed out. To quote Ernest Scott again, after Labor’s victory, "upon the local political horizon there was not a cloud when Parliament settled down to the work of the session."[9]

How the War Was NOT Reported↑

The Great War has been described by Niall Ferguson as the "first media war in history."[10] That is incorrect. The Boer War (1899-1902), the Boxer Rebellion (1900-1901), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) were all extensively covered by the international press, the last named conflict seeing the first use of cinematography in conflict reporting as well. Australian George Hubert Wilkins (1888-1958) took motion pictures of the First Balkan War in 1912 and photographed the fighting from a plane. In fact, despite the endless acres of newsprint expended upon it at the time, the First World War was arguably less a media war than its immediate predecessors.

The international press reported the Great War extensively and for over four years it dominated their output, both in terms of the fighting and domestic issues. What the press did not do was examine it intensively. In Australia that situation was compounded by the strategic control of the war resting firmly in London. A combination of political and military censorship in all the combatant states, plus the loyal adherence of newspaper proprietors, editors and journalists to their national war efforts, ensured that for much of the war the true nature of the fighting was conveyed to the public fitfully and in a diluted fashion. The public craved, not unnaturally, news of a war which had drawn in so many of its young men. In many cases, including in Australia, what they regularly received was filtered, delayed or polished up. When, for example, Australians finally read on 8 May 1915 (about a fortnight late) a newspaper report of the Anzac landing the article was not all rosy – delays in treating the wounded and heavy casualties were mentioned, for example. Yet the Allies’ tenuous hold on tiny strips of beach and slopes was buried under the grand claim that there had "been no finer feat in this war than this sudden landing in the dark and storming the heights" as the "raw colonial troops in these desperate hours proved worthy to fight side by side with the heroes of Mons, the Aisne, Ypres, and Neuve Chapelle."[11]

The Australian government was determined to control war reporting by sending as few journalists as possible and then limiting their access to the frontline, which when it did occur, was only under strict conditions. The Boer War, especially in its first, most active year, had been covered by a relatively large number of Australian correspondents representing many different newspapers. Reporters in South Africa had complained of the ubiquitous censorship, which some thought was intended to conceal the "awful blunders" and "farcical mistakes"[12] of the British military, yet this paled before that prevailing in the First World War. In 1914 war journalists were incorporated into the national war machine and were regarded as a link, a potentially suspect one, between the public and their soldiers, not as dispassionate observers.

C.E.W. Bean, Official Correspondent↑

Therefore, as far as Australian journalists were concerned, the First World War was not open to all comers. After a brief sideshow in September 1914, when Frederick Burnell (1880-1958) of the Sydney Morning Herald was sent to cover the occupation of German New Guinea, it was the government’s intention that the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF) would be accompanied by just one Official War Correspondent. This ended up being Charles Bean (1879-1968), who was elected by his journalist peers in September 1914 – an interesting combination of industrial democracy and closing the door on everybody else. Bean’s defeated opponent was Keith Murdoch (1885-1952), who was working at the time for the Sydney Sun. He would later visit Gallipoli briefly but crucially. Other Australian war correspondents were very few in number. At the most generous count, eleven journalists and two photographers covered Australia’s war on all its fronts and some of these reporters were there for brief periods only. Bean was unique among Australian correspondents in being there for the duration, from Anzac to the last battles Australia fought on the Western Front, a feat which had few parallels elsewhere in the Empire. Unlike his British counterparts, the tireless and physically brave Bean seemed to be able to go wherever he liked, interviewing, observing, collecting. In fact, as at Gallipoli, his movements were often controlled more than he liked, but his work rate was astonishing.

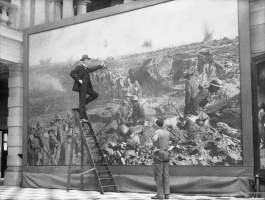

A modern history of Australia’s Great War has described Bean as a "colossus" and as "both a historian and agent of memory."[13] As a war reporter, Bean was less successful. His articles were seen by some editors as prosaic and were not always published in full or immediately; this occurred as early as the Gallipoli campaign. British journalists used to the "colour stuff" were often preferred and the military communiqué was often simply reproduced in Australian newspapers, providing a view of the war that had been thoroughly sanitised. At Gallipoli, Bean was trumped by the more experienced British journalist Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (1881-1931) in publishing the first detailed account of the Australians’ landing on 25 April 1915. Even Keith Murdoch’s four-day inspection of Gallipoli in September 1915 had a greater impact than any of Bean’s dispatches, as Murdoch’s subsequent article, which criticised aspects of the campaign, was judiciously distributed throughout London, helping seal the expedition’s fate. But Bean was never just a journalist. His eyes were set firmly on the future; he was planning how events would be commemorated as those events were taking place. As he assiduously filled notebook after notebook and toured the battlefields, Bean was collecting the raw material he would use as editor and writer of the Official Histories of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Later he would play a crucial role in establishing the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, a secular temple for a raw new capital. Bean did not create the Anzac legend, but he helped shape it and endow it with the historical gravitas needed to form a national myth.

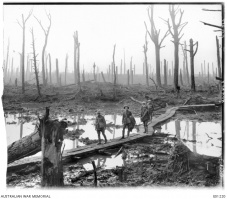

Besides Bean, the most enduring contribution from Australian correspondents in the First World War probably came from its photographers, George Hubert Wilkins and James Francis "Frank" Hurley (1885-1962), though they did not arrive on the Western Front until the middle of 1917, just in time for the agony of the Third Battle of Ypres. Hurley’s carefully composed images of the blasted and drowned landscape of Passchendaele match in quality the cold beauty of his Antarctic photographs with the Shackleton expedition and remain familiar to many people today. The picture of the soldiers crossing the flimsy footbridge at Chateau Wood may bring the war home far better than any journalist could manage in words. That is precisely why so few of the photographs taken by Wilkins or Hurley were published during the war.

Like almost all correspondents in the First World War, Australian reporters were constricted by layers of censorship, which commenced in the field before proceeding upwards through the military and political hierarchies. News moved slowly from the front, often ending up out of date by the time it reached Australia, where morning editions generally missed out on the recent events. Yet war correspondents censored themselves as much as others censored them. They could not tell the full story of industrialised warfare to those at home, at least not while it was happening, and perhaps it was an impossible task anyway. Bean was willing to criticise censorship, but he also knew that much of the war consisted of "horror and beastliness and treachery on which the writer, anxious to please the public, has to throw his cloak."[14]

The Press and the Government – Allies, Not Enemies↑

At home the Australian government was quite prepared to come down heavily on those it considered dangerous or simply contrary. This included the press, whose influence was feared and sometimes exaggerated by politicians in this period. Prior to 1914 there was in several nations "a dramatic expansion of the political public sphere,"[15] including discussion of international issues. Governments saw the press as a significant factor in formulating national policy via swaying public opinion. But suspicions on the part of the Australian government were unfounded. As Gorman and McLean noted, "Journalists were largely in sympathy with government policy during the war, and there was little conflict between the mass circulation newspapers and political and military intentions."[16] The press in Australia was neither the mouthpiece of a warmongering government nor its master. It was its ally.

The sympathetic alliance between the Australian media and its political leaders endured through Joseph Cook’s brief conservative government at the outset of war and the subsequent Labor Party ministries of Andrew Fisher (September 1914 to October 1915) and his successor William Morris Hughes (1862-1952). After Hughes’s espousal of conscription split the Labor party in September 1916, he led a largely conservative coalition until the end of the war. The mainstream press found it easier to support Hughes when he was leading the Nationalists than when he was leading Labor. For the Melbourne Age in November 1916, Hughes and his pro-conscription supporters had "confessed their immitigable obligation as representatives of the nation, to serve the interests of the nation according to the precepts of conscience and the dictates of honour and patriotism."[17]

Hughes, whether as attorney general in Fisher’s government or as prime minister, has been criticised for attempting to stifle public debate in Australia during the First World War. His "extraordinarily dominant and energetic personality" (to borrow Joan Beaumont’s description)[18] did not brook opposition and his obsession with perceived enemies such as the International Workers of the World or Sinn Fein was often irrational. During the second conscription referendum campaign in late 1917, for example, Hughes manipulated the censorship provisions to impede the ability of publications such as the Advocate and the Australian Worker to publish their "anti" views freely. Hughes might have been able to suppress some dissident articles but he could not control the public’s vote. In the October 1916 referendum, conscription was rejected by a majority of 2.2 percent; this margin increasing to 7.6 percent by the time of the second referendum in December 1917. As a result of these defeats, some of the major newspapers sought sectarian targets such as "disloyal" Irish Catholics, exacerbating prejudices that had existed well before the war. The rejection of the two referenda also demonstrates the extent to which the Age, the Brisbane Courier and others could sell newspapers but not necessarily their sentiments, and this despite the government’s efforts to seduce or batter public opinion into the shape it wanted.

In the last quarter of the 19th century war reporting, assisted by the introduction of the cable service, became a staple of newspapers. The Great War further encouraged newspaper readership in Australia. Whereas in 1907 overseas stories occupied 17.5 percent of Australian news space, under the impetus of the war this figure rose to 35.3 percent by 1917. But there were major production problems to overcome. Australian newspapers depended totally on imported newsprint and the sharp increase in the cost of this item after 1914 meant that rural newspapers especially had to reduce their size or amalgamate with former competitors. Significant metropolitan publications also raised their costs and printed fewer pages. Thus there was less space for news when there was more to report - though that news might be dubious or anodyne. Cable charges, such an important factor in reporting news from the Middle East or the Western Front, rose an astonishing 600 percent over the course of the conflict. The economic difficulties did not suppress the public’s desire for news, a demand which after the war helped fuel a spirited struggle between newspaper owners for market dominance in the final years before radio became a serious competitor to the press.

The conservative sympathies of the mainstream press were clearly shown in their stance during the period of industrial dispute in the eastern states of Australia commencing in August 1917. The immediate and long-term causes of the widespread strikes were complex – three years of war that seemed to be going nowhere was almost certainly one factor – and ultimately the unions were defeated. The mass movement to lay down tools seemed to confirm the government’s fear of extremist conspirators and the major newspapers responded accordingly. They called for strike-breakers to come to the wharves and the mines and they came, especially from rural areas, helping drive the unions back to work. The Melbourne Punch featured photographs of some of these strike-breakers on 23 August 1917.[19] Here, in a difficult year of the war, were genuine heroes, at least as far as the press was concerned.

Conclusion↑

On Tuesday, 12 November 1918, Australian newspapers published news of the armistice. By today’s standards the announcements look rather understated. The news of the armistice was generally placed around page five, after such items as the classified advertisements, the angling news on the upper Derwent and the shipping reports – see the Mercury (Hobart). The West Australian (Perth) went so far as to title their article "Surrender of the Arch Enemy" but most headings were relatively mild in tone.[20] A public holiday was proclaimed and people took to the streets to rejoice, but clashes between soldiers and unionists also occurred as the former sought to establish their loyalty to nation and empire, a sign of the social divisions produced by the war. These fractures would endure long after the newspapers had stopped reporting the celebration of victory and were examining the consequences of peace.

Richard Trembath, University of Melbourne

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald, 31 July 1914.

- ↑ Argus, 3 August 1914.

- ↑ Bulletin, 13 August 1914.

- ↑ Cited in Cathcart, Michael and Darian-Smith, Kate (eds.): Stirring Australian Speeches. The Definitive Collection from Botany to Bali, Melbourne 2004, p. 135.

- ↑ Scott, Ernest: The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Volume XI, Australia During the War, Sydney 1936, p. 57.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War 1914-1918, London 1999, p. 215.

- ↑ The Labor Call, 13 August 1914.

- ↑ The Australian Worker, 1 October 1914.

- ↑ Scott, Official History 1936, p. 52.

- ↑ Ferguson, Pity of War 1999, p. 212.

- ↑ Ashmead-Bartlett, Ellis: Untitled, in: Argus, 8 May 1915.

- ↑ A.G. ‘Smiler’ Hales cited in Anderson, Fay and Trembath, Richard: Witnesses to War. The History of Australian Conflict Reporting, Melbourne 2011, p. 39.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: Broken Nation. Australians in the Great War, Sydney 2013, p. xxv.

- ↑ Cited in Anderson and Trembath, Witnesses to War 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Clark, Christopher: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914, London 2013, p. 226.

- ↑ Gorman, Lyn and McLean, David: Media and Society in the Twentieth Century. A Historical Introduction, Oxford 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Age, 15 November 1916.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: The Politics of a Divided Society, in: Beaumont, Joan (ed.): Australia’s War, 1914-18, Sydney 1995, p. 38.

- ↑ Punch, 23 August 1917.

- ↑ Mercury, 12 November 1918; West Australian, 12 November 1918.

Selected Bibliography

- Anderson, Fay / Trembath, Richard: Witnesses to war. The history of Australian conflict reporting, Carlton 2011: Melbourne University Press.

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Ferguson, Niall: The pity of war, New York 1999: Basic Books.

- Gorman, Lyn / McLean, David: Media and society in the twentieth century. A historical introduction, Malden 2003: Blackwell Publishing.

- Macleod, Jenny: Reconsidering Gallipoli, Manchester; New York 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Osborne, Graeme / Lewis, Glen: Communication traditions in 20th-century Australia, Melbourne; New York 1995: Oxford University Press.

- Williams, John Frank: Anzacs, the media and the Great War, Sydney 1999: UNSW Press.