Introduction↑

Knowing what we do about the nature of the First World War, it is difficult to grasp the fact that the outbreak of the war in 1914 was welcomed by some sectors of public opinion in Europe. Although this varied greatly from country to country and within populations, it was still the case that, for some, the news of war was regarded positively. This article will explore what the reasons for this were.

One simple explanation, of course, was that practically no one, from the ordinary citizen to the heads of government and military generals, imagined or could begin to imagine the reality of the war that would unfold. There was little awareness of the terrible effects of modern weapons or the fact that they would result in a long war, although books, articles and newspapers did refer to the negative impact a conflict might have. There were exceptions of course – famously Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) as well as Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke (1800-1891) and Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) had envisaged a long war; Jan Gotlib Bloch (1836-1902) had predicted that modern war would prove long and an economic catastrophe. Western military observers, however, largely ignored the lessons of attrition and the difficulty of carrying out speedy offensives that were evident in the Russo-Japanese and Balkan wars.

The "short war illusion" was, in part, a consequence of the lessons being drawn from history: the most recent war between the major European powers, the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, which remained a relatively fresh memory for the populations of 1914, had only lasted from 19 July 1870 to 29 January 1871, around six months. There was an awareness of the earlier Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, particularly among Europe’s military; indeed, the Napoleonic wars received especial attention. But although this earlier period of warfare lasted cumulatively more than twenty years, it was made up of a series of much shorter individual wars and between them there had also been brief phases of peace. Before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the future belligerents’ plans all envisaged a rapid conflict whose outcome would be decided by one or two decisive large battles.

This was far from being irrational – indeed, had the German army won the battle of the Marne, which it came very close to doing, this was what might well have happened: in this scenario, the war would have been more or less over on the Western Front and it would not have taken long for it to end on the Eastern Front as well.

It is therefore important to realise that when the threat of war loomed in 1914, the populations of Europe thus did not react in response to what was going to happen – rather, they responded to what they imagined, or what they were capable of imagining, was going to be the likely outcome.

A European War↑

This was particularly the case in the three countries which were at the heart of the conflict – the French Republic and the German and Russian empires. This was the context of the images of enthusiastic soldiers leaving for war in 1914 and the trains of mobilised troops covered in bellicose graffiti – nevertheless it is important not to exaggerate this phenomenon; these cases were only ever a very small minority of overall troops and populations.

France↑

In France, although there had been some evident concern among the public in the weeks before the outbreak of the conflict, the atmosphere was not pro-war, despite the significant hawk-like change to the military service law of the previous year, 1913, which lengthened the period of service from two to three years. At the end of July 1914, the French press was far more focused on a domestic scandal – the trial of Henriette Caillaux (1874-1943), the wife of one of the leading politicians of the French Third Republic, which took place from 22 to 29 July. Her husband was president of the most important political party in the country, the Radical Party. She was on trial for her actions on 16 March 1914 when she shot and killed Gaston Calmette (1858-1914), the editor of Le Figaro, a newspaper that had waged an ongoing campaign against her husband. She feared Calmette would publish "intimate letters" that she had exchanged with her husband Joseph Caillaux (1863-1944) prior to their marriage while she was his mistress and Caillaux was still married to his first wife, whom he divorced in March 1911.

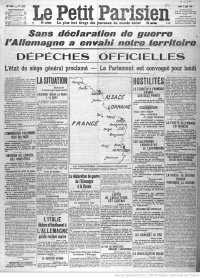

When war suddenly loomed as a threat in the last days of July, French public opinion was far from being unanimous. In Paris and in the larger towns, some relatively significant nationalist demonstrations took place, but pacifist demonstrations organised by the socialist party and the CGT trade union were more numerous. In contrast, in rural France there was little knowledge of the international developments; the countryside was focused on work in the fields at this time of year and few of its inhabitants had the leisure time to read newspapers, practically the only news medium during this period. When the church bells began to ring on 1 August and it became clear that this was not to warn of fire but to announce mobilisation for war, the first reaction was one of stunned shock and consternation. But opinion in the towns and countryside was dramatically changed by the German invasion of Belgium and Luxembourg. Faced with what, to many French, appeared to be a characteristic German act of aggression, the vast majority of the public believed that it was necessary to defend the country. Only in a handful of cases, however, did this situation provoke enthusiasm; the overwhelming attitude was one of resolution and resignation.

Germany↑

German public opinion evolved quite differently, largely because, as Wolfgang J. Mommsen (1930-2004) has shown, the "idea that a war was inevitable" was relatively widespread in Germany.[1] One reason was that since the 1911 Morocco Crisis, the Germans had become convinced that their legitimate colonial expansion was being blocked by the French and the English. Another extremely influential idea in German public opinion was the fear of encirclement resulting from the coalition between France, Great Britain and Russia, an idea exacerbated by another largely unfounded fear, which had continued to grow nevertheless, of a Russian threat to Germany: there was a widespread belief that in the event of a war, Germany risked being overwhelmed by the Russian masses within a few years, Russia having recently reformed its army to increase its strength. This helps explain why, when the threat of war loomed in July 1914, there was evidence of real enthusiasm for war among the middle classes in Germany, often accompanied by profoundly anti-Russian attitudes. Recent historical work by Roger Chickering and Jeffrey Verhey has highlighted this and the extent to which such patriotic manifestations were also aimed at the German socialist movement, whose patriotism was considered suspect by the German right in the weeks preceding Germany’s entry into the conflict. War enthusiasm was much less evident among the working classes, and, even if, as in France, it proved impossible to organise a large anti-war protest strike movement in time to actually stop the conflict, there were a series of major demonstrations across German cities that mobilised hundreds of thousands of workers under the banners of the Social Democratic Party to oppose Germany going to war in the last week of July, as Jeffrey Verhey has shown. As Gerd Krumeich has emphasised, the response to the threat of war in working class urban areas was often one of depression and desolation, and the SPD leadership only fully rallied to support the war after the Russian invasion of East Prussia.[2]

These initial reactions to the news of war were soon followed by a second phase during which a sense of worry dominated throughout the German population. The idea of a fresh and joyful war, following a model that dated back to 1859, dissipated rapidly in 1914; despondency at the news of war continued amongst workers. Indeed, recent historical research by Jeffrey Verhey, Benjamin Ziemann and Wolfgang Kruse has shown that the mood among German workers and peasants was not pro-war; many were fearful but practically none were able to speak out against the war after the SPD Reichstag deputies decided to vote for war credits. The rapid drop in war enthusiasm in Germany was also linked to the tough war conditions that unfolded. For the German military leadership, it was necessary to first fight the French army before then shifting to focus upon fighting the Russians. The German public viewed the latter contest as much more important and threatening.

Russia↑

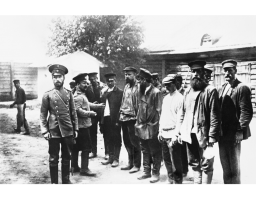

In the case of Russia there was no one general monolithic reaction to the outbreak of war. Responses varied widely from patriotic fervour to anti-war despondency, militancy and disorder.[3] Russian urban populations generally responded to German Russophobia with a wave of anti-German sentiment. Patriotic fervour was widespread among the Russian educated classes; war enthusiasm was markedly more moderate amongst the workers. Yet it is noteworthy that in St Petersburg – a name which was immediately deemed too German-sounding and replaced with Petrograd – although the preceding period had been one of social and political unrest in the city, with barricades and strikes, a situation that bordered on the revolutionary, such social protest ceased when faced with the outbreak of international war. The Russian Duma held a historic session where all the parties affirmed their patriotism, with the exception of the Bolshevik and Menshevik Deputies who refused to vote for war credits; however, they were very few in number, with nine and five Deputies respectively. It is important to note that the segment of the working class population that supported them and whose views they reflected was underrepresented in the Duma: the war was unpopular with key segments of the urban working class population.

In contrast to the mass patriotic mobilisation in the cities, there was widespread despondency, open dissent and desertion in many rural districts where conscripted peasants engaged in drunken riots which were suppressed by the military, with hundreds killed. The immense majority of the Russian population were peasants who did not understand the reasons for mobilisation or experience patriotic fervour. But their viewpoint counted for little. Also, their discontent did not develop into an organised mass refusal to mobilise, even though those reporting to the mobilisation points were delivering themselves up to the harsh demands of the Russian army. Once drafted, many proved disciplined and obedient soldiers; however, the mass desertions before 1917 show that it is necessary to make careful distinctions, as morale and obedience fluctuated greatly, and the Russian army also used widespread coercive discipline to keep troops in line, making it difficult to assess troops’ opinions of the war.

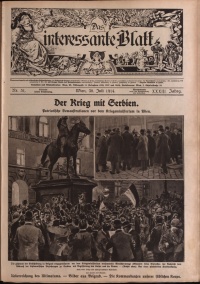

Austria-Hungary↑

It was Austria-Hungary which bore the brunt of the responsibility for unleashing this war which had seen large swathes of Europe mobilise in several days. Austria-Hungary had acted in order to take vengeance on Serbia which it viewed as responsible for the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914), a month earlier, on 28 June 1914, in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, territory recently annexed by Austria-Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was an unusually structured multinational state and it was conceivable that the many different groups among the population, in particular the German and Slav populations, would react to the news of war in different ways. In reality, although the sudden outbreak of a European war came as a shock, the attitude of the Austro-Hungarian population was even more of a surprise in its relative coherence: there was very little difference in terms of how the German, Hungarian, Polish and Czech populations of the empire, and even the Serbian population of Bosnia-Herzegovina, responded to the war. They displayed very similar patriotic reactions to the populations of nation-states in their defensive rallying around the state and the Emperor. This behaviour was so unexpected and difficult to understand that Leon Trotsky (1879-1940), who was in Vienna during this period, believed it was not possible to find a theoretical explanation for it, instead suggesting that those mobilised for war were simply glad to escape the boredom of everyday life. Although he was writing based on his experiences in a German part of the Empire, the situation was more or less similar throughout Austria-Hungary.

Great Britain↑

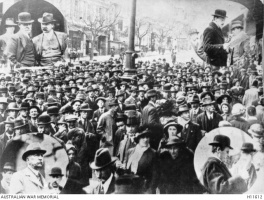

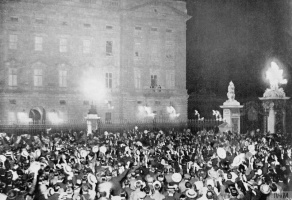

It had been over fifty years since Great Britain had intervened militarily in a conflict on the continent. The Liberal Party, in government since 1906, wished to continue this state of affairs and avoid entangling Great Britain, which, as a global power, had other overseas concerns in India and Persia to weigh against continental ones. The United Kingdom’s domestic situation was unstable in light of the tense Irish political situation surrounding the implementation of Home Rule, various social problems, and suffragette agitation. This merely bolstered the view that getting involved on the continent was not in Britain’s interests. The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933), was convinced that the European problems could be solved through negotiation, and had long resisted accepting any transformation of Britain’s entente with France and Russia into an actual alliance. At the outset of the July Crisis in 1914, Britain was focused on the crisis in Ireland rather than on Serbia, with widespread indifference to the outcome of the Austro-Hungarian-Serbian clash amongst the British general public. In addition, when on Sunday 2 August, Germany issued its ultimatum to Belgium, the British were enjoying a long bank holiday weekend, which meant that while the most unprecedented war in history was being unleashed, the British public was literally "on holiday", enjoying a Monday off work. The cabinet, however, was badly divided on whether or not to enter the war, and concerned about public reactions: there were major anti-war demonstrations, including one that rallied thousands of people in Trafalgar Square in London in the days preceding the entry into the war. Ultimately, it was the German invasion of Belgium that allowed the cabinet figures in favour of assisting France – Edward Grey and Winston Churchill (1874-1965) in particular – to win. Arguably it was not until Grey’s speech to the House of Commons the day before the British entered the war on 4 August 1914 that public opinion swung solidly behind intervention.

But public opinion reacted rapidly to the government’s action, responding with almost unanimous approval – the Liberals, Conservatives and Labour all voted for war credits, while even the very liberal newspaper The Manchester Guardian rallied to the war effort in response to the invasion of Belgium. Men from all backgrounds, but particularly from the middle classes, responded in their hundreds of thousands to the call for military volunteers to serve – Britain did not have conscription in the first two years of the war and the 2 million men who volunteered are evidence of a widespread, if not universal, commitment to the national cause. As the British historian John Keiger has emphasised, in the British case, a country that was extremely divided in 1914 was suddenly united by the war.[4]

Serbia and Belgium↑

Serbia and Belgium, as small states, faced a simple dilemma in 1914 – fight or surrender – in contrast to the larger European countries which were by and large masters of their own destiny during the outbreak of the conflict. Faced with the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum, Serbia found itself in a difficult position, already exhausted by the two Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 which had ended just barely a year earlier, on 10 August 1913, with the Treaty of Bucharest. Serbia had no real means of effectively resisting the much more powerful forces of Austria-Hungary; however, this did not prevent the Serbian press from aggravating the situation with patriotic and belligerent articles. There was, however, virtual national unanimity within Serbia around the decision to refuse to capitulate, with the exception of two socialist deputies. It should be noted that these two men represented rural regions given that Serbia almost completely lacked any industry.

Belgium had no stake in the unfolding war and was only brought into the conflict because the German Schlieffen Plan set out that the German army would cross Belgium as part of its invasion of France. Germany offered to pay the costs that would arise from this military invasion of Belgium, presenting it as merely a process of military transit into France, and was convinced that the Belgians would permit the passage of the powerful German army. However, this turned out not to be the case – both the Walloon and the Flemish populations of the country were indignant at the prospect of what was effectively an invasion of their sovereign territory and a breach of Belgian neutrality. According to Belgian historians, such as Jean Stengers (1922-2002), and in particular, war contemporary Henri Pirenne (1862-1935), it was a sense of national honour which motivated the majority of Belgians, who were angered by the way in which Germany, one of the signatories of the treaty that had pledged to guarantee Belgian neutrality, had broken its obligations.[5]

Colonies and Dominions↑

The European war took on the appearance of a global conflict right from the outset due to the use of colonial troops. France was the only state to use black African troops on the European battlefield. It also employed troops from the Maghreb, mobilised from its North African territories. Britain used Indian soldiers on the Western Front. The British "white" Dominions also entered into the war when Britain did. On 31 July 1914, the Australian Prime Minister Joseph Cook (1860-1947) stated that “when the Empire is at war, so is Australia at war.”[6] Over the course of the conflict, over 1 million Australian, Canadian, South-African, New Zealand and Newfoundland volunteers would fight in Europe, while a large number of Indian soldiers also fought in Mesopotamia, Egypt and elsewhere.

Japan↑

Japan, which was allied to Great Britain, was also obliged to enter the war on the Allied side as part of the terms of its alliance treaty which had been renewed in 1911.[7] The Japanese military supported entry and part of the country’s press provoked an anti-German movement. Nonetheless, Japan refused to send combat troops to Europe and focused its war contribution on conquering Germany’s colonial enclave at Tsing-tau in China, which it swiftly took in 1914.

Non-participating States↑

Within days, much of Europe had entered the war, with the exception of the Netherlands, Switzerland the Scandinavian states and in the south, the Ottoman Empire, Italy and the Iberian Peninsula. The case of Switzerland was special. The 69 percent of the population that was German-speaking favoured Germany, while the 22 percent of the population who were Francophone were largely pro-French in their attitudes to the conflict.[8] Thus, the internal Swiss situation was fragile. However, the army, which was mobilised from 1 August 1914, remained neutral and helped to maintain the neutrality of the country, even if its commander General Ulrich Wille (1848-1925) was openly pro-German. The Swiss economy was majorly disrupted by the war, but none of the belligerents had any interest in violating Swiss neutrality – rather the opposite. They sought to benefit from the communication and transport channels between the belligerents that a neutral Switzerland sustained at the centre of Europe. The Netherlands was also economically disrupted, particularly by the temporary influx of 1 million Belgian refugees. The Scandinavian countries were also affected economically and politically by the war: in Denmark, the majority of the population was hostile to Germany, in Norway, there was a majority in favour of Great Britain, while the Swedish public favoured Germany, to the extent that there was an important element calling for Sweden to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers. In the south of Europe, neutral Spain was divided by the conflict into two sides, pro-Allied and pro-Central Powers, with Alfonso XIII, King of Spain (1886-1941), effectively maintaining the country’s position of neutrality throughout the war.

Portugal↑

The situation evolved differently elsewhere where other neutral countries ultimately found it impossible to remain out of the conflict. Portugal had little real stake in this war beyond being an old ally of the United Kingdom.[9] The British government believed it was preferable that Portugal remain neutral, and the Portuguese population was largely indifferent. Yet since the 1910 revolution, which had established the Portuguese Republic, the Democratic Party, the most radical of the Republican factions, believed it would be in the interests of the Republic to unite the country behind a great national cause, and that the war offered this opportunity. Following on from German provocations, particularly in Africa, where Portuguese Angola bordered the colony of German South-West Africa, Portugal declared war on Germany on 9 March 1916. Two unfortunate Portuguese Divisions were the victims of Portugal’s First World War gamble – they were "routed" by the German offensive in Flanders in April 1918. There was scarcely a Portuguese church that did not erect a memorial to the dead of the conflict.

Italy↑

Italy was the only major European power to not immediately enter the war and was the subject of strong lobbying from both sides to join them. Italy’s situation was unique, as before the conflict it had been allied to Germany and Austria-Hungary as part of the Triple Alliance, but had also coveted Trieste and the Trentino which were Austro-Hungarian territories. The majority of the Italian population – the peasantry – were indifferent to the European conflict and largely illiterate and focused on local issues; however, in the towns, a pro-Entente movement which called for Italy to intervene on the side of the Entente developed. This was a predominantly middle class movement, which saw the war as a chance for Italy to take those coveted Austro-Hungarian territories known as the "irredente" lands – the largely Italian-speaking areas of the Trentino and Trieste in particular. In contrast, the Italian urban working classes were largely pacifist. Major demonstrations took place in Rome and Milan in favour of intervention. The Italian right, which had originally been more favourable towards the Central Powers, now rallied to the pro-Entente interventionist national movement. The interventionist demonstrations ultimately gave rise to what became known as "radiant May" which ended with Italian entry into the war on the side of the Entente Powers in May 1915. The patriotic fervour in the cities was real, and the mobilised peasantry, although often lacking knowledge of the war’s causes, would in many cases fight with significant determination, although, as in the Russian case, morale fluctuated and the army employed harsh coercive discipline which makes any assessment of soldiers’ opinion on the war difficult to gauge.

The Balkans↑

The war had emerged from the Balkans but had, in the first months, passed the majority of the Balkan states by. However, as the conflict continued, the belligerents multiplied their efforts and pressure to draw the Balkan states into the war on their side.

In spite of its defeat in the first Balkan War, the Ottoman Empire was no longer the "sick man of Europe". It had been bolstered by the rise of the pre-war Young Turk movement, which had become resolutely nationalist following its successful coup, and which envisaged reconstructing the Empire along the lines of a Turkish national state in order to strengthen it. The Young Turk leadership also aspired to extend the borders of the state to encompass the Turkic populations of the Caucasus and Turkestan who were under Russian rule, and some members saw the outbreak of war as a potential chance to take this territory from Russia while Russia was distracted on other fronts. Not all of the Young Turk leadership were in favour of entering the war, however, and it was ultimately Ismail Enver Paşa (1881-1922), who was profoundly pro-German, who drew Turkey into the war against Russia by attacking Russian naval ships in the Black Sea. The Ottoman Empire declared its entry to the war on the side of the Central Powers on 2 November 1914.

With regard to the Balkan states of Romania, Bulgaria and Greece, all three had monarchs who were of German origin and whose sympathies lay with Germany. Nevertheless, the stance of each of these three countries was different. The mass of the population were rural peasantry who again played little role in the decisions taken regarding entering the war. Public opinion was determined by the middle classes in urban centres – a small segment of the overall population. Germany badly needed Bulgaria as an ally as this would facilitate its communication links with the Ottoman Empire; however, exhausted by the Balkan Wars, Bulgaria was reluctant to get involved in the conflict even if it desired to retake the part of Macedonia that lay inside Serbia’s borders. Ultimately, Germany and Austria-Hungary bought Bulgarian intervention by offering the country an enormous financial subvention, and Bulgaria declared war on Serbia on 14 October 1915. Romania, which coveted territory from both Russia and Austria-Hungary, focused on opportunistically entering the war on the side of whoever was most likely to be victorious. In 1916, Romania believed that this would be the Entente side, following a series of Russian successes, and declared war on Austria-Hungary on 27 August 1916. As for Greece, its leading political figure Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936) hoped that by supporting the Allies that he could realise his "great idea" of reconstituting a modern version of the Byzantine Empire; however, he faced the strong opposition of the pro-German Greek court which wanted Greece to remain neutral. Ultimately it was France that removed Greece’s diplomatic options with regard to the conflict, by sending French troops to Salonika (modern Thessaloniki) on 1 October 1915, in something of a fait accompli, and creating an Allied army there that the French labelled the "Armée d’Orient". In June 1917, the Allies deposed Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923), and, led by Venizelos, Greece then officially entered the war on the Allied side on 29 June.

Thus by 1917, for a wide range of very diverse reasons, almost all of Europe had entered into the war – although each state’s view of the conflict differed so much that it is fair to say that in many ways they were entering different ‘wars’. Indeed, for the Balkan states, the First World War can reasonably be described as the third Balkan War. Public opinion also played a varied role in decision-making depending on the sophistication of a state’s political structures and systems of response to citizens, levels of literacy and press saturation, and industrial development.

A Global War↑

The United States↑

In 1917, the war became even more of a global conflict with the entry of the United States.[10] At the outbreak of the conflict in 1914 there had been no reason for the United States to enter what it saw as a European war. The American population was divided in its attitude towards the conflict. Certain groups supported Britain or Germany, while the mass of the immigrant population was largely indifferent – having left Europe to start a new life in America, many were uninterested in European affairs. As for the President, the Democrat Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), who had been elected in 1912, even if he believed that it was the mission of the United States to promote democracy worldwide, he did not think that it should enter the war. Wilson had formally declared American neutrality at the outbreak of the conflict. In a message to the Senate on 19 August 1914, he had called upon Americans to remain neutral – “impartial in thought as well as action”. During the Presidential election campaign in 1916, he ran on the popular slogan “he kept us out of the war”.

What led to Wilson changing his views towards American entry into the conflict, as well as to a shift in attitude among the American public to favouring intervention on the side of the Entente, with the obvious exception of German-Americans? One answer is the contested wartime issue of "freedom of the seas". In the early phase of the war, Wilson had protested strongly against the Allied maritime blockade of Germany; however, the President was more vociferous in his condemnation of the German response, which was unrestricted submarine warfare. Following the torpedoing of the British liner the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, with the loss of almost 1,200 lives, including 128 American victims, there was such an outcry in the United States that Germany was forced to moderate its submarine warfare practices. However, as the conflict continued and the blockade tightened, Germany believed that adopting a form of restricted submarine warfare was far less efficient and so on 31 January 1917, it once more declared unrestricted submarine warfare, which posed a major threat to U.S. shipping and trade routes and resulted in the sinking of American vessels. In addition, due to the blockade, American agriculture and industry had largely become focused on supplying the Allied war effort. If the Allies had lost the war, American financial losses would have been considerable. Moreover, once the Germans revived unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, American goods, destined for transatlantic transport to supply the Allies, piled up on the quays, as ships were reluctant to leave port due to the submarine threat, resulting in considerable disruption. It is still debated to what extent these economic considerations influenced Wilson; the German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare, however, marked a humiliation of his peace efforts to bring the belligerents to negotiations and the Zimmerman telegram of spring 1917 reinforced this. Moreover, they certainly had an impact on changing the point of view of the American population in general. The President was focused on acting, not on the grounds of the United States’ material interests, but rather on the basis of considerations such as American prestige, the promotion of democratic ideals and the rights of neutrals. On 2 April 1917 the United States entered into the war as an "Associate" of the Entente countries, not an ally, a binding term of obligation that the US rejected. The majority of Americans now sympathised with the Entente but this did not result in a widespread desire to volunteer to fight in the war themselves, and there was some resistance to conscription. America had only a small army which few Americans considered a major force; when the government decided to enlarge it into the large military necessary to fight the war, there were very few volunteers. However, when the state introduced conscription in order to ensure the necessary manpower, mobilising 4.8 million men, Americans reacted stoically, largely with patriotism.

Latin American Countries↑

The American government believed that other states on the American continent should share its views on the war. However, this proved not to be the case; among the twenty states of Latin America, just one, Brazil, entered into the war in October 1917, and participated only in a very limited fashion, although it did send some soldiers to Europe. Cuba and Panama also entered the conflict; both were heavily dominated by the United States, and in addition, the small states of Central America took part: Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Others, such as Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic were satisfied with merely breaking off diplomatic relations with the Central Powers. The other major states – Mexico, Venezuela, Columbia, Argentina and Chile – remained neutral. In fact, Latin America felt far removed from the conflict and little concerned by it; as the historians Armelle Enders and Olivier Compagnon note: “viewed from Latin America, the memory of the First World War is so non-existent and inaudible that it is as if the conflict never happened.”[11]

China↑

There was one other major power that entered into the war – China, a weak and divided state at the time, despite its immense population. China entered the conflict on 1 August 1917 for one main reason, which was to prevent Japan from keeping control of Germany’s Far East colonies after the war ended. The Chinese state saw little active participation in the war; the main Chinese contribution was by Chinese labourers, who were brought to Europe by the Allies to provide manual labour for their demanding war efforts. However, the negotiations to obtain most of these labourers, as well as their transport to Europe and employment there, took place before the official entry of the Chinese state into the conflict.[12]

Conclusion↑

The war that broke out in 1914 rapidly became known as the "Great War" in Britain and France, to the extent that the first edition of the major history of the conflict by Pierre Renouvin (1893-1974) which appeared in 1934 was entitled: La Crise européenne et la Grande Guerre (The European Crisis and the Great War). Obviously, it was only after 1945 that the term "First World War" entered common usage. Yet, among historians, debate continues as to the degree to which the 1914-1918 conflict was truly a "world" war compared to its successor conflagration of 1939-1945. Certainly, in terms of public opinion, aside from the "white" dominions, colonial populations had little say in their involvement in the 1914-1918 conflict or state decision-making regarding entering the war.

Ultimately the essential question regarding the First World War is not why did it happen – there have been innumerable studies written on this question – but rather what drove it on. Here, public attitudes matter considerably. If one leaves aside the enormous Russian peasantry which fought with courage and resolution without really knowing what the war was about, particularly at the outset, it is the strong patriotic and national feeling of the rural and urban middle classes of Central and Western Europe that was the main motor that drove and sustained the conflict. Herein perhaps lies the major original aspect of the Great War – its main root was the sense of national feeling which, during the nineteenth century, had spread to the majority of European populations and dominated over other ideas such as pacifism or internationalism. While socialism had developed into a movement of considerable importance during the same period, ultimately it could stand up to the more dominant forces of nationalism and patriotism, which overwhelmed other public attitudes once war broke out.

Jean-Jacques Becker, Historial de la Grande Guerre

Section Editor: Roger Chickering

Translator: Heather Jones

Notes

- ↑ Mommsen, Wolfgang J.: The topos of inevitable war in Germany in the decade before 1914, in: Berghahn, Volker R. / Kitchen, Martin (eds.): Germany in the age of total war. Essays in honour of Francis Carsten, London 1981, pp. 23-45.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: L’entrée en guerre en Allemagne, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les sociétés européennes et la guerre de 1914-1918, Nanterre, 1990.

- ↑ Sanborn, Joshua: The mobilization of 1914 and the question of the Russian nation. A reexamination, in: Slavic Review 59/2 (2000), pp. 267-89.

- ↑ Keiger, John F. V.: Britain’s ‘union sacrée’ in 1914, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les sociétés européennes et la guerre de 1914-1918, Nanterre, 1990.

- ↑ Stengers, Jean: La Belgique, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les sociétés européennes et la guerre de 1914-1918, Nanterre, 1990.

- ↑ Quoted in Winter, Jay: La première guerre mondiale, Paris 1990.

- ↑ Schwentker, Wolfgang: L’Asie du sud-est avant et pendant la guerre, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2004.

- ↑ Favez, Jean-Claude: La Suisse pendant la guerre, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2004.

- ↑ Teixeira, Nuno Sevariano: Entre neutralité et belligérance, l’entrée du Portugal dans la Grande Guerre, Florence 1994.

- ↑ Kaspi, André: Les Etats-Unis d’Amérique face à la guerre en Europe, août 1914-avril 1917; Les Etats-Unis d’Amérique dans la guerre, avril 1917-novembre 1918, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2004.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 889

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: Les Travailleurs chinois et la France pendant la Grande Guerre, in: Ma, Li (ed.): Les travailleurs chinois en France dans la Première Guerre mondiale, Paris 2012.

Selected Bibliography

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les sociétés européennes et la guerre de 1914-1918. Actes du colloque organisé à Nanterre et à Amiens du 8 au 11 décembre 1988, Nanterre 1990: Publications de l'Université de Nanterre.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: L'année 14, Paris 2004: A. Colin.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: La Première Guerre mondiale, Paris 2003: Belin.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: Dictionnaire de la Grande Guerre, Brussels 2008: A. Versaille.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Krumeich, Gerd: La grande guerre. Une histoire franco-allemande, Paris 2008: Tallandier.

- Cochet, François / Porte, Rémy (eds.): Dictionnaire de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2008: R. Laffont.

- Feiertag, Olivier: La déroute des monnaie, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard, pp. 1163-1176.

- Geinitz, Christian: Kriegsfurcht und Kampfbereitschaft. Das Augusterlebnis in Freiburg. Eine Studie zum Kriegsbeginn 1914, Essen 1998: Klartext.

- Gregory, Adrian: The last Great War. British society and the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (eds.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2014: Schöningh.

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1993: Kartext Verlag.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom united. Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Raithel, Thomas: Das 'Wunder' der inneren Einheit. Studien zur deutschen und französischen Öffentlichkeit bei Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, Bonn 1996: Bouvier.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: The mobilization of 1914 and the question of the Russian nation. A reexamination, in: Slavic Review 59, 2000, pp. 267-289.

- Verhey, Jeffrey: The spirit of 1914. Militarism, myth and mobilization in Germany, Cambridge; New York 2006: Cambridge University Press.

- Ziemann, Benjamin: War experiences in rural Germany, 1914-1923, Oxford; New York 2007: Berg.