The Opening Phase, 1914-1916↑

The Australian Imperial Force (AIF), raised after the outbreak of war in August 1914, was a volunteer force. Under the Defence Act of 1903, Australia’s small regular army could not be deployed overseas. Compulsory militia service for males aged eighteen to sixty years had been introduced in 1911, but this was for purposes of home defence only.

At first the restriction of the AIF to volunteers had little impact on Australia’s contribution to the war. The number of enlistments in 1914 and early 1915 more than covered the government’s initial commitment to London, and there were few losses in battle. However, with the mounting casualties of the Gallipoli Campaign, the pressure for conscription grew. Beginning in September 1915, a Universal Service League, modelled on the British National Service League, demanded that the federal government modify the Defence Act to permit conscription for overseas service.

The ruling Australian Labor Party (ALP) government faced profound political difficulties in responding to this demand. Its dominant figure, William Morris "Billy" Hughes (1862-1952), who was Attorney General (1914-1915) and Prime Minister (1915-1923), had no personal objection to the principle of compulsion. His political base was the trade union movement, in which the "closed shop" was sacrosanct. But many of his ALP colleagues and the wider industrial movement were bitterly opposed to conscription. Since the war had brought a declining standard of living for the working classes, they believed that there should be a "conscription of wealth" as well as of labour.

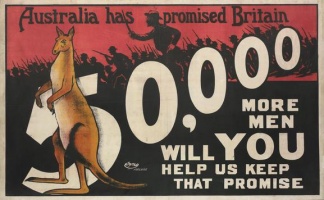

Though potentially explosive, the issue of conscription was kept under control until mid-1916. Britain had introduced conscription for single men and childless widowers in January 1916, and extended this to married men in May 1916. New Zealand, too, passed legislation in May 1916 conscripting non-Maori males. This would be extended to Maoris in June 1917. Hughes returned from a long visit to London in August 1916 convinced that Australia must follow suit. Voluntary enlistments in August 1916 reached only 6,345, well below what the British Army Council calculated was needed to replace the heavy losses that the AIF was suffering on the Somme.

Hughes’ political options, however, were limited. Although the ALP had a majority in both houses of parliament, Labor parliamentarians were certain to split on the issue. Nor could Hughes introduce conscription by regulation under the emergency powers granted the government in October 1914 through the War Precautions Act. This would have required the concurrence of the Executive Council (which was, in effect, Hughes’ cabinet) and, in the opinion of Chief Justice Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (1845-1920), would have been unconstitutional. So Hughes decided to put the issue to the Australian people, believing that with a public mandate he could neutralize the opposition of at least some of his critics.

The campaign which followed in September and October 1916 was bitterly contested. The fault lines along which Australian society divided were complex and are still not entirely clear, given the lack of sophisticated psephology in 1916. However, with some important exceptions, Australians voted in ways that reflected their class, religion and gender, with class perhaps being the dominant variable.

The 1916 Conscription Referendum↑

The "Yes" Campaign↑

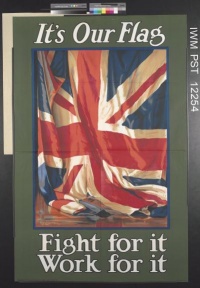

The case for conscription was generally championed by the political and social elites, including the leadership of the Protestant churches, the majority of the press, business leaders and the conservative Liberal Party (the federal opposition). For these largely middle-class Australians, the military case for compulsion seemed irrefutable. They accepted the British command’s view that there was no other way of supplying the AIF with the reinforcements it needed. They also believed that the war was a just cause; a noble struggle in defence of the British Empire and the values for which it stood. The enemy was a brutal one whose atrocities in Belgium continued to be given prominence in the Australian press.

Leaders of the Protestant churches also saw the war as a righteous struggle between the interests of the kingdom of God and the satanic forces of Germany led by the anti-Christ Kaiser. Many Protestants even saw the war as a blessing, purifying the people of Australia through suffering, sacrifice and self-abnegation. Though there was not a shred of biblical authority justifying it, one clergyman concluded that Jesus would have voted yes. Some Christians, however, issued their own manifesto condemning warfare and what they saw as the new religion of the state in which "the State replaces God, and the National flag replaces the Cross."[1] The advocates of conscription also argued that the burden of the war must be shared equitably. It was invidious that only those who chose to serve risked being killed or injured. Australia owed it to the men who had made that sacrifice to ensure that others followed them. Equality of sacrifice was an argument rooted partly in the agony of bereavement and loss: why should my son, father or husband die while yours lives? But it was also a debate about the obligations of citizenship. Military service should not be a matter of individual choice. The supreme duty which a democrat owed to his country was to fight for it. This was a powerful argument, highlighting the contradiction at the heart of any democratic state, which both enshrines individual freedom but requires for its survival that its citizens be willing to die in its defence.

For the yes case, voluntarism had a further flaw, in that it threatened to weaken the Australian race in the future. If only volunteers, who were assumed to be the fittest, the most virile, and the most morally sound of the male population, were willing to die, the race might become degenerate. Even more alarming than the eugenics effect would be the vulnerability of Australia to external threats. If Britain were defeated in Europe, the Royal Navy lost its dominance in the Pacific, and Australia had only weaklings to defend it, who would contain the threat of Germany and Japan in the region?

All of these arguments were positioned within the unquestioning identification with the British Empire that had underpinned Australia’s initial commitment to the war. Even though the performance of Australian troops at Gallipoli and the Somme inspired a surge of national pride, for many Australians, British interests were indivisible from their own. Loyalty to Britain therefore became the quintessential test of civic virtue in the rhetoric of the yes case. Those who opposed conscription were not nationalists with a different understanding of Australia’s interests. Rather they were "disloyal", stigmatized with insinuations of treason, treachery and support for Germany.

The "No" Campaign↑

The opponents of conscription mirrored each of the arguments for conscription with a counterargument. Dominated by the trade unions, but not limited to them, the anti-conscription groups also spoke the language of loyalty and equality of sacrifice. But for them, it was loyalty to class as well as to nation; and equality meant that the capitalist "plutocrats", who were shamelessly profiting from the war, should share with the working classes the economic burden of inflation and rising prices. Unless there was a "conscription of wealth", there should be no conscription of labour.

Opponents of conscription challenged the accuracy of official estimates of the number of reinforcements needed to replace the AIF losses. Moreover, they feared that military conscription would be a harbinger of industrial conscription. The rights that the union movement had wrested from capitalism by bitter industrial action over the past twenty years would be in jeopardy and the very existence of the male working class at risk. With men drafted overseas, women – or even worse, cheap Asian labour – would take their place. White Australia, a core value of the young Australian nation, would be at risk.

Like the yes case, the opponents of conscription also invoked the discourse of civil liberties, claiming that it was a violation of democracy to force men to fight and kill against their will. These rights arguments were given weight by the fact that it seemed that the country was heading towards a form of despotism. Using the War Precautions Act, the Hughes government stifled dissent through heavy censorship of the media and the partisan repression of public meetings.

Sectarianism↑

To the already febrile mix of the conscription debate was added Protestant-Catholic sectarianism. Some 21 percent of the Australian population was Catholic;[2] most of them were working class and of Irish extraction. Their religious leaders were also, with few exceptions, Irish by birth or training. In contrast to the Protestant leaders, the Catholic hierarchy did not initially adopt a formal position on conscription. Divided on the issue themselves, they declared that conscription was a secular rather than a moral issue, which parishioners should resolve in terms of their individual consciences. The Catholic laity, it seems, largely opposed conscription, though whether this was because of their class, ethnicity or religion has been much debated. Many Catholics had been aggrieved by the withdrawal of state aid to non-government schools in the late 19th century. Their Irish extraction also made many Catholics naturally distrustful of the imperial history of Britain that so entranced the Anglo-Australian loyalists. Probably many Catholics were also radicalized by the uprising of Irish republicans in Dublin in Easter 1916 in an attempt to end British rule.[3]

The Role of Women↑

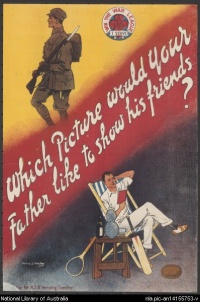

It was a long campaign of eight weeks, during which public order disintegrated. Each side held huge mass rallies, with crowds numbering up to 100,000 in Sydney. Physical violence and crude disruptive tactics became common on both sides. Notably this violence often targeted women, as did the propaganda of both sides. The yes case exhorted women to fulfil their traditional biological role as wives and mothers and provide husbands and sons as a sacrifice to the nation. If women supported conscription, it was also argued, they would have the chance to demolish the final argument against their claiming full citizenship. The no case, for its part, turned the gendered argument on its head. As they saw it, women, as mothers, should protect their offspring from the ravages of war.

On both sides of the campaign women were catapulted into the public sphere that was traditionally dominated by men. Middle class leaders of organizations such as the Australian Women’s National League, the National Council of Women and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union spoke from public podiums and organized petitions. Socialist women also became regular speakers at public gatherings, although behind the scenes they continued to bear most of the traditionally female duties. Working class women, in turn, used often spontaneous public meetings as a forum for expressing their frustration, anger and grief.

All of this public contestation became deeply personalized and bitter in communities where everyone knew each other. Small rural towns were riven apart by the public naming of families who had, or had not, sent their sons to the war. Friendships were left in tatters by personal abuse, the labelling of men still at home as "shirkers" and accusations of cowardice, dishonesty, treachery and betrayal of men at the front.

The Result↑

On 28 October 1916, Australians finally voted. The result was no, but only by a margin of 72,456 votes or 3.2 percent of the valid votes cast. The states were split: Victoria, Western Australia and Tasmania voted yes; New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia, no. New South Wales was most strongly against. Many words have been written analysing the result. Class was a strong influence, with the working classes and trade unionists largely voting no and the middle classes, yes. So too was gender, birthplace and religion. Catholics voted strongly against conscription; women, generally for. Those born in Britain tended to vote yes, a fact that may help account for the stronger yes vote in Western Australia where the proportion of the population born in Europe was higher than the national average. Primary producers often voted no, presumably fearful of the impact of conscription on their economic productivity and angry at the shortage of labour and the wartime control of wheat and other primary goods.[4] However, none of these variables were exclusive. Some voters defected from their class or normal political allegiances. The one conclusion we can reach with confidence is that, after a debate of intense complexity and passion, each Australian cast his or her vote in a way that was personal and idiosyncratic.

One cohort whose vote was of particular significance was the AIF itself. Hughes was so sure that the soldiers, with whom he felt a strong rapport, would vote yes that he scheduled their polling day more than a week before the main vote. The AIF’s support for conscription, progressively released during the campaign, would then set an example for Australians at home. By early October 1916, however, it appeared that a majority of soldiers in France might vote no. In the end, after a hastily improvised campaign to sway their vote, there was a small majority for yes.

The 1917 Conscription Referendum↑

As many had predicted, the conscription debate split the ALP at federal and state levels, consigning it to the political wilderness federally for the next decade. Hughes himself stayed in power only by forming a coalition, the National Party, with his former political opponents, the Liberals. Leading this hybrid party, he won the federal election of May 1917 on a "Win the War" ticket. It was clear that the vote against conscription had not been a vote against the war.

The issue of conscription, however, would not go away. In 1917, voluntary recruitment continued to fall below the levels needed to replace the losses on the Western Front. Hughes’ conservative coalition partners also would not let the matter rest, particularly as the United States introduced conscription immediately after declaring war in April 1917 and Canada followed its example in July 1917 (despite deep opposition from its French Catholic minority). So Hughes felt he had no option but to put the question to a popular vote again. With majorities now in both houses he could have passed legislation but this, he was advised, would take too much time (the first conscripts might reach Europe only in October 1918).[5] Moreover, Hughes had promised in the May 1917 elections to refer conscription back to the people if the strategic situation deteriorated.The referendum proposal in 1917 was more modest than in 1916, but the debates it triggered were even more bitter and divisive. All the arguments for and against conscription were rehearsed again, but the tone was more strident, irrational and hysterical. In contrast to 1916, the no case was championed, in Melbourne particularly, by a Catholic priest, Archbishop Daniel Mannix (1864-1963). Sensitive to the concerns of his laity, Mannix played to the longstanding sense of Catholic marginalization in Australian society and the class identity of his working-class parishioners, who were in no mood for compromise after the ruthless crushing of a general strike between August and October 1917. Having himself arrived in Australia from Ireland only four years earlier, Mannix also strongly identified with the Irish Home Rule cause. Blessed with a commanding public persona, and a capacity for acerbic wit and oratory, he would become a source of profound aggravation to Hughes and the loyalists.

Another thorn in Hughes’ flesh in the 1917 campaign was Labor Queensland Premier Thomas Joseph Ryan (1876-1921). Although willing to support voluntary enlistment, Ryan opposed conscription as an abuse of government power. Like Mannix, he was more than a match, tactically and temperamentally, for the short-fused Hughes. By the time the conscription campaign ended, the state of Queensland politics was so volatile that Hughes, who was bombarded with an egg during one rally at Warwick near Brisbane, thought (with some exaggeration) that the state was "ripe for revolution."[6]

The Result↑

Once again, on 20 December 1917, the majority of Australians voted no: 1,181,747 versus 1,015,159. The general patterns of voting seemed to have been similar to 1916 but the no margin was slightly larger. Victoria joined New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia in voting no. Not surprisingly, given some very public confrontations between Ryan and Hughes, Queensland’s no vote rose by 22,000. Yet even in "loyal" Western Australia the no vote increased. Only in South Australia did the no vote decline, perhaps because in this referendum German-Australians, who were strongly represented in the winemaking district of the Barossa Valley, were disenfranchised.

The soldiers of the AIF, whose votes were so important to the legitimacy of the government’s case, again voted yes. Even so, the margin was slight and it was thought that the majority for yes came from men in camps in Britain and on transports rather than those at the front.

The Aftermath↑

The defeat of the referendum meant conscription was dead as a policy option. Despite a growing gap between casualties and enlistments in 1918 – a gap so great that some battalions had to be cannibalized and the maintenance of five infantry divisions was at risk – the AIF remained a volunteer army until the end of the war. This left two important legacies. The first was that post-war Australian remained divided not only along sectarian lines but between those who had volunteered and those who had not. The volunteer became the superior citizen, entitled not just to honour but to benefits such as preferential employment, medical care and soldier settlement land schemes. Secondly, the fact that the AIF remained an all-volunteer force fuelled the development, from 1916 on, of the mythic representation of the Australian soldier as the citizen in arms. In the valorising narrative that became known as the Anzac "legend", the "digger", or common soldier, became the embodiment of civic values. He was not a professional soldier, but a natural fighter. The competence for which he was renowned was a testament to, and affirmation of, the values and lifestyle of Australian society: a society which, in the writings of one of the key exponents of the legend, Charles Bean (1879-1968) was egalitarian, relatively classless and shaped by the experience of living in the Australian rural districts, or "the bush". It was a representation that was only partially true, but it resonated so powerfully with the Australian cultural imagination, and the need of the bereaved to invest the huge losses of war with meaning, that it became the dominant narrative of the First World War. It has endured, albeit in modified form, to this day.

Joan Beaumont, Australian National University

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Gibson, P.M.: The Conscription Issue in South Australia, 1916-1917, in: University Studies in History 4 (1963), p. 70; Jauncey, Leslie C.: The Story of Conscription in Australia, London 1935, pp. 198, 206.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics: 2112.0 - Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1911, online: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/0/B8982A23D75F18B6CA2578390013015D/$File/1911%20Census%20-%20Volume%20II%20-%20Part%20VI%20Religions.pdf (retrieved: 30 May 2014).

- ↑ See Gilbert, Alan D.: The Conscription Referenda, 1916-17. The Impact of the Irish Crisis, in: Historical Studies 14/53 (1969), pp. 54-72.

- ↑ Withers, Glen: The 1916-1917 Conscription Referenda. A Cliometric Re-Appraisal, in: Historical Studies 20/78 (1982), pp. 38-46.

- ↑ Connor, John: Anzac and Empire. George Foster Pearce and the Foundations of Australian Defence, Melbourne 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ Fitzhardinge, L.F.: William Morris Hughes. A Political Biography, II, The Little Digger 1914-1953, London 1979, p. 228.

Selected Bibliography

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Damousi, Joy: Socialist women and gendered space. Anti-conscription and anti-war campaigns 1915-18, in: Damousi, Joy / Lake, Marilyn (eds.): Gender and war. Australians at war in the twentieth century, Cambridge; New York 1995: Cambridge University Press, pp. 254-273.

- Evans, Raymond: Loyalty and disloyalty. Social conflict on the Queensland homefront, 1914-18, Sydney; Boston 1987: Allen & Unwin.

- Fewster, Kevin: The operation of state apparatuses in times of crisis. Censorship and conscription, 1916, in: War & Society 3/1, 1985, pp. 37-54.

- Fitzhardinge, L. F.: The little digger 1914-1953. William Morris Hughes. A political biography, volume 2, London 1979: Angus & Robertson.

- Gilbert, Alan D.: The conscription referenda, 1916-17. The impact of the Irish crisis, in: Historical Studies 14/53, 1969, pp. 54-72.

- Jauncey, Leslie C.: The story of conscription in Australia, London 1935: Allen & Unwin.

- McKernan, Michael: Australian churches at war. Attitudes and activities of the major churches 1914-1918, Sydney; Canberra 1980: Catholic Theological Faculty; Australian War Memorial.

- O'Farrell, Patrick James: The Catholic Church and community. An Australian history, Kensington 1985: New South Wales University Press.

- Shute, Carmel: Heroines and heroes. Sexual mythology in Australia, 1914-1918, in: Damousi, Joy / Lake, Marilyn (eds.): Gender and war. Australians at war in the twentieth century, Cambridge; New York 1995: Cambridge University Press, pp. 23-42.

- Smart, Judith: The right to speak and the right to be heard. The popular disruption of conscriptionist meetings in Melbourne, 1916, in: Australian Historical Studies 23/92, 1989, pp. 201-219.

- Turner, Ian: Industrial labour and politics. The dynamics of the labour movement in Eastern Australia, 1900-1921, Canberra 1965: Australian National University Press.