During the War↑

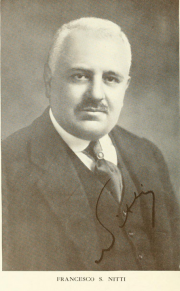

Even before the Great War Francesco Saverio Nitti (1868-1953) was well known as expert on the problems of social and economic backwardness in southern Italy. As left-wing liberal, he had become Minister for Agriculture, Industry and Commerce in the cabinet of Giovanni Giolitti (1842-1928) in 1911, promoting the law on state monopoly of life insurance, which introduced the National Insurance Institute (INA). In the summer of 1914 for a short time he advocated for neutrality in the war. However, he quickly changed his mind and convinced himself of the necessity for Italy to enter the war on the side of Entente. Like democratic interventionists Gaetano Salvemini (1873-1957) and Leonida Bissolati (1857-1920), he supported the idea that the war could be a unique opportunity for Italy to carry out radical economic and institutional transformations. He emphasized in particular the new planning and directive role to be played by the state during the war. When it came to the problems of post-war economic reconversion and social instability, Nitti became the spokesman for an economic program with a convergence of state direction and private initiative, with the support of a significant injection of foreign capital, in particular from the USA. Accordingly, he took part in the 1917 Italian diplomatic mission to the United States, the purpose of which was to obtain a broad loan.

Nitti as Minister after Caporetto↑

In the aftermath of the military defeat of Caporetto, Nitti was engaged by new Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (1860-1952) as minister of the Treasury and de facto assumed the control of entire war economy. As such, he succeeded in partially re-equilibrating the dramatic financial situation of Italy, but failed in containing galloping inflation. With particular attention to the social problems of the war, he introduced a compensatory social policy, which was aimed firstly at combatants and veterans. Nitti was at the forefront of the initiative to create a national combatants’ agency (opera nazionale combattenti), which provided insurance policies to veterans and helped them find jobs as civilians, as well as the ministry for war pensions, which centralized social policy for war disabled, widows and orphans.

Post-War Period: Nitti as Prime Minister↑

Nitti’s understanding with other prominent figures in the government did not survive the war. Already in the first weeks after the armistice, a disagreement over foreign policy with Orlando and especially Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922) was exacerbated and forced Nitti to resign in January 1919. The economic crisis and social instability of the country, worsened by the international isolation of Italy at the peace conference in Paris, led to the swift fall of the Orlando Cabinet. Nitti, who had shown himself to be amenable to the adoption of a system of proportional representation and social reforms, received a broad consensus in the establishment of a new government. The goal of creating a “social democracy,” with a parallel development of economic reforms and welfare policies (in particular compulsory unemployment insurance and accident insurance for all male and female employees) clashed with the harsh reality of a country lacerated by deep social conflicts and paralyzed by strikes and occupations of factories and land. The victory of mass parties such as the Socialist Party and the Partito popolare (Catholic Party) at the elections in November 1919 dissolved the majority of liberals in the chamber who supported (though not entirely) Nitti’s government. The occupation of Fiume at the hands of “legionaries” (volunteers and mutinous troops) headed by Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) further worsened the government’s precarious stability and damaged the already difficult relationship with international allies. Nitti was forced to resign in June 1920.

Nitti was later made target of fascist aggressions, which persuaded him to leave Italy in 1924. He settled down in France, where he became a prominent figure of anti-fascism in exile, even though he always distanced himself from the anti-fascist positions of both the Socialists and Catholics. He also continued his activity as an author of economic and political studies. During World War II he was arrested by the Gestapo and detained until the end of war in Austria with Édouard Daladier (1884-1970) and Paul Reynaud (1878-1966), both former French prime ministers. After the war he returned to Italy and was elected to the new democratic parliament, though he did not play a significant role. He died in February 1953.

Pierluigi Pironti, Städtisches Museum Braunschweig

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Adorni, Daniela: Orlando al governo, in: Isnenghi, Mario / Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni. La Grande Guerra. Dall’Intervento alla 'vittoria mutilata', volume 3, Turin 2008: UTET, pp. 501-515.

- Barbagallo, Francesco: Francesco S. Nitti, Turin 1984: Unione tipografico-editrice torinese.

- Bartocci, Enzo: Le politiche sociali nell'Italia liberale, 1861-1919, Rome 1999: Donzelli.

- Monticone, Alberto: Nitti e la grande guerra (1914-1918), Milan 1961: Giuffrè.

- Sabbatucci, Giovanni: La crisi dello stato liberale, in: Sabbatucci, Giovanni / Vidotto, Vittorio (eds.): Storia d'Italia, 1914-1943, volume 4, Rome 1998: Laterza, pp. 101-167.

- Sirignano, Fabrizio Manuel / Lucchese, Salvatore: Pedagogia civile e questione meridionale. L'impegno di Francesco Saverio Nitti e Gaetano Salvemini, Lecce 2012: Pensa multimedia.