The Radicalization of the German Right and the Founding of the German Fatherland Party in 1917↑

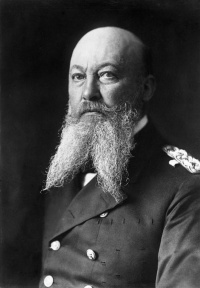

The German Fatherland Party (Deutsche Vaterlandspartei) was founded on 2 September 1917. The initiative for the new party came from Wolfgang Kapp (1858-1922), then Landschaftsdirektor in East Prussia, former navy grand admiral and member of the Prussian upper chamber, Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930), and Johann Albrecht zu Mecklenburg (1857-1920) from the German Colonial Society. Its purpose was to mobilize the political right in a broad catch-all movement (Sammlungsbewegung). Central to the party’s foundation was the attempt to fight the weakening of Germany’s war effort by opponents of a war that included annexation and advocates of peace and democratic reform. The Peace Resolution of the majority parties in the parliament (SPD, Center Party, and the left-liberal Freisinn) from 19 July 1917, the announcement of the “Easter Decree” earlier on 7 April 1917, in which Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) promised democratic reform after the war, and the founding of the Independent Social Democratic Party between 6 and 8 April 1917 sparked Kapp’s agitation for the founding of the German Fatherland Party. Earlier, in May 1916, Kapp had distributed critique over the government in a pamphlet and was supported by Tirpitz, who had become a powerful symbolic center of opposition to Theobald vom Bethmann Hollweg’s (1856-1921) government and Emperor Wilhelm II. Tirpitz’ antagonism toward the government increased after he resigned on 15 March 1916 as grand admiral of Germany’s navy over conflict about enforcing Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare against the Allies instead of using it as a flexible maritime war strategy.

War Aims, Political Activism, and Social Mobilization 1917-1918↑

The Fatherland Party grew out of the War Aims Movement and was supported by several organizations on the right like the Pan-German League and the Agrarian League. The party never aspired to stand for future elections and only sought to assist a future government in winning a victorious peace. Like the Independent Committee for a German Peace (Unabhängiger Ausschuss für einen Deutschen Frieden), the Fatherland Party did not frame a detailed program for domestic politics, other than denouncing democratic reform. The party mostly advocated a military victory that would ensure territorial expansion. In particular, Belgium was to be divided into Flemish and Walloon territories, the French industrial areas of Longwy-Briey were to be annexed, and the Courland, Livonia, Estonia, and Lithuania were to be brought under German power to serve as future settlement territories for ethnic Germans. The war aims, however, were not laid out in a specific program and remained flexible in scope and outlook as the party focused on domestic politics to propagate a “Siegfrieden” (victorious war). The Fatherland Party aimed to mobilize all social classes and political milieus. To the frustration of anti-Semitic sections of the party, Tirpitz also welcomed Jews as members. The new party soon counted between 300,000 and, supposedly, 800,000 individual and corporate members (the party officially claimed a membership of 1.2 million), but it could not mobilize mass constituencies among workers and Catholics, and in liberal regions of southern Germany. The mobilization of members in more than 2,000 local chapters of the Fatherland Party all over Germany, however, revealed the radical nationalist potential in German society. The Fatherland Party was especially successful in urban centers as well as in areas east of the river Elbe. The party’s most successful strongholds were in Pomerania, Saxony, East Prussia, and Silesia, as well as in the Duchy of Lippe and Westphalia.

The Legacy of the German Fatherland Party after the First World War↑

The dissolution of the Fatherland Party in December 1918, which became effective on 1 February 1919, predicted the failure of the traditional politics of notables (Honoratiorenpolitik) of the “old” right from imperial Germany, which, during the Weimar Republic, found itself competing with “new” movements and parties over leadership, propaganda, and mass mobilization. The proximity of the former German Conservative and large sections of the National Liberal electorate to the new German National People’s Party (Deutschnationale Volkspartei, 1918/1919-1933) made this party a reservoir for former activists of the German Fatherland Party (including Tirpitz, who was elected as a member of parliament in 1924). Smaller groups of former Fatherland Party members became active in the German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei, 1918/1919-1933). Kapp upheld his vision of authoritarian leadership in a civil-military dictatorship after 1918, and organized the Kapp Putsch between 13 and 17 March 1920 together with General Walther von Lüttwitz (1859-1942), with the support of Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937). The putsch resulted from the stipulations of the Versailles Treaty to reduce the size of Germany’s army to 100,000 troops from January 1920, and the order of the Reichswehr Minister, Gustav Noske (1868-1946), to dissolve the free corps unit “Brigade Ehrhardt” in February 1920. Kapp and Lüttwitz mobilized members of the army, the navy, and free corps units for the putsch and gathered several members of the radical right for a shadow cabinet, including leading members of the Pan-German League like Paul Bang (1879-1945). Tirpitz, who became active in organizing plans for a dictatorship with several right organizations in Bavaria in 1922/23, condemned the putsch as premature and poorly planned. Although the Kapp Putsch resulted in a civil war and most of the government ministers under the leadership of the Social Democratic chancellor Gustav Bauer (1870-1944) had to leave Berlin, it failed due to the resistance of the army and the resilience of civil servants who overwhelmingly participated in a successful general strike.

Björn Hofmeister, Freie Universität Berlin

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Eley, Geoff: Reshaping the German right. Radical nationalism and political change after Bismarck (2 ed.), Ann Arbor 1990: University of Michigan Press.

- Hagenlücke, Heinz: Deutsche Vaterlandspartei. Die nationale Rechte am Ende des Kaiserreiches, Düsseldorf 1997: Droste.

- Hofmeister, Björn: Between monarchy and dictatorship. Radical nationalism and social mobilization of the Pan-German League, 1914-1939, Washington, D.C. 2012: Georgetown University.

- Retallack, James N.: Notables of the right. The Conservative Party and political mobilization in Germany, 1876-1918, London 1988: Allen & Unwin.

- Scheck, Raffael: Alfred von Tirpitz and German right-wing politics, 1914-1930, Atlantic Highlands 1998: Humanities Press.

- Stegmann, Dirk: Die Erben Bismarcks. Parteien und Verbände in der Spätphase des wilhelminischen Deutschland. Sammlungspolitik 1897-1918, Cologne; Berlin 1970: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.