Introduction↑

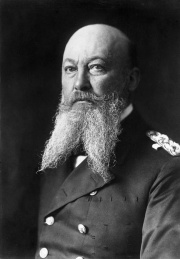

Appointed Secretary of State of the Imperial Naval Office in 1897, Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930) was one of Germany’s most influential politicians prior to the outbreak of war in 1914. His plan of building a powerful battle fleet, which would be able to challenge the Royal Navy in order to realize Germany’s aspirations for a “place in the sun”, had a deep impact upon the course of both German foreign policy as well as domestic politics. The result of this challenge was a naval arms race with the Entente powers, which Germany eventually lost.

Wartime↑

Tirpitz played no significant role during the July Crisis. His attempt to take over command of the navy when war broke out failed. He was only allowed to give advice to the Chief of the Admiral Staff, Admiral Hugo von Pohl (1855-1916). After the outbreak of war, it soon became clear that Tirpitz’s plan had not only failed politically but also strategically. Since any attempt to break the distant blockade established by the British Grand Fleet would have been suicidal, the High Seas Fleet decided to stay on the defensive hoping to whittle down the strength of the Grand Fleet with a strategy of guerilla-warfare (Kleinkriegsstrategie). Deeply disappointed and despite early setbacks during the Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1914, Tirpitz nevertheless continuously demanded a more offensive role, ignoring the great risks which such a strategy entailed. After heavy infighting, the navy eventually decided upon a hit-and-run-strategy. By attacking the British East Coast in 1914 the High Seas Fleet hoped to lure out parts of the Grand Fleet and to annihilate them.

This strategy, however, soon proved a failure and was given up after the loss of the armored cruiser Blücher in January 1915. Instead, Germany’s naval leadership now reverted to unrestricted submarine warfare around the British Isles. Hesitating at first, for he regarded the number of submarines as too small, Tirpitz soon became one of the most important advocates of this new strategy. To Tirpitz’s great dismay this strategy, which had proved successful, had to be given up for political reasons in May 1915 after US-protests against the sinking of the British liner Lusitania. Tirpitz continued to lose influence. In March 1916 chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) used a new crisis over the introduction of unrestricted submarine warfare to oust Tirpitz from his office, thus eventually getting rid of a stubborn opponent of his policy, a maneuver which eventually led to Tirpitz’s resignation. In fact, this resignation was nothing but a dismissal by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941). Both of them were fed up with Tirpitz’s continuous criticism of their own policy and his intrigues behind the scenes against the government by leaking official documents to rightist newspapers or by giving misleading information on important matters regarding submarine warfare. By not inviting him to an important meeting about the introduction of submarine warfare, the chancellor eventually hoped to force Tirpitz to ask for his resignation as a result of this open affront. Tirpitz, deeply hurt, asked the Kaiser for a longer holiday. To his own surprise, instead of granting this holiday the Kaiser asked him to hand in a request for his dismissal formally. On 19 March 1916 Tirpitz left his office after nineteen years in the service of the Kaiser and the navy.

Years of Opposition↑

Deeply disappointed, Tirpitz soon became the center of intrigues against the chancellor and even the Kaiser. In 1917 he helped to found the German Fatherland Party (Deutsche Vaterlandspartei), becoming its first chairman. After surprising initial success this right-wing movement, which demanded far-reaching annexations and a reactionary domestic policy, lost support when it became clear that Germany would lose the war.

Post-war↑

After some time in hiding, Tirpitz re-entered politics in 1919/20. In his Memoirs (1919) he not only tried to justify his policy, but he also openly attacked Germany’s former leadership. At the same time, he supported anti-Weimar right-wing groups. In 1924 he became Reichstag deputy for the German National People’s Party (Deutschnationale Volkspartei). His plans of becoming chancellor of a right-wing coalition-government in 1924 or even president in 1925 were successfully thwarted by his opponents within the bourgeois parties. To his great disappointment, Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1932) who had been elected president with Tirpitz’s support in 1925, refused to follow his advice and to establish an authoritarian regime as well as to take up a stronger stand against Germany’s former enemies by both rejecting the Locarno Treaty in 1925 and the Young Plan in 1929/30.

Michael Epkenhans, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Selected Bibliography

- Epkenhans, Michael: Tirpitz. Architect of the German high seas fleet, Washington, D.C. 2008: Potomac Books.

- Kelly, Patrick J.: Tirpitz and the Imperial German Navy, Bloomington 2011: Indiana University Press.

- Salewski, Michael: Tirpitz. Aufstieg, Macht, Scheitern, Göttingen; Zurich; Frankfurt a. M. 1979: Musterschmidt.

- Scheck, Raffael: Alfred von Tirpitz and German right-wing politics, 1914-1930, Atlantic Highlands 1998: Humanities Press.

- Uhle-Wettler, Franz: Alfred von Tirpitz in seiner Zeit, Hamburg 1998: Mittler.