Background↑

Jan Smuts (1870-1950) achieved prominence when he passed the Cambridge Law Tripos in one year. This was a notable achievement in Smuts’ case because he grew up in a Dutch (Afrikaans) environment where English was not his first language, and where he did not attend school until the age of twelve. He became, at thirty-two, the youngest attorney-general in Paul Kruger's (1825-1904) Transvaal government before the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. He served in a legal capacity, but also led a Boer commando into the Cape Colony in an attempt to raise support for the Boer cause. The negotiation tactics that he employed at the 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging, and the 1909 Union discussions were instrumental in ensuring their success. He worked closely with his friend and colleague Louis Botha (1862-1919) to bring about a united South Africa, loyal to the British Empire, after representative government was awarded to the Transvaal in 1907.

Outbreak of War and Rebellion, 1914↑

Smuts had his work cut out for him when war broke out in 1914. His Ministry of Defence consisted of himself and his administrator. Within weeks he had appointed a Director of Recruiting and other necessary administrators to manage the war requirements. For example, his ministry had to source weapons and ammunition from various sources because little was available in the Union and what there was, was mostly returned to England in August 1914, along with the Imperial garrison which had been stationed in South Africa following the end of the Anglo-Boer War. Smuts was responsible for drawing up the initial invasion plans for German South West Africa soon after war broke out, and for presenting the case for invasion to Parliament, which, according to the Union Defence Act of 1912, had to sanction conscription and military action outside the Union. A significant section of the South African population, mainly Afrikaans-speakers who were anti-Empire, objected to South Africa going to war with Germany as the latter had provided support during the Anglo-Boer War. Following Parliament’s approval to invade German South West Africa, thousands of the most militant and disaffected Afrikaner republicans rebelled.

When the Afrikaner rebellion started during September 1914, Smuts was responsible for coordinating the action and keeping an eye on the home and German fronts when Prime Minister Louis Botha took to the field. Smuts and Botha conferred daily by telegraph wire about the situation. Smuts’ most controversial action at this time was approving the execution of rebel Josef Johannes "Jopie" Fourie (1879-1914) for treason. Fourie had been captured wearing military uniform and had not resigned his commission from the Union Defence Force. Fourie’s execution earned Smuts the bitter enmity of his Afrikaner opponents.

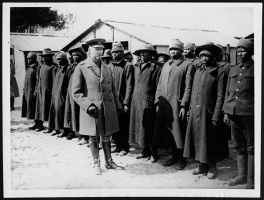

Warrior: South West Africa and East Africa, 1915-1916↑

The German South West African campaign, which had been trickling along during 1914, was re-launched on 26 December 1915. Despite opposition from Smuts and others about his safety, Louis Botha himself took command of the forces. This left Smuts in charge of the Union. In April 1915, when it was clear the rebels were unlikely to rise again, Smuts joined the forces as commander of the Southern Column in German South West Africa. He did not see much action, and was mainly responsible for consolidating the Union forces operating in the south and relocating them to the north in support of Botha's movements.

When it became apparent that the campaign in South West Africa was drawing to an end, Smuts actively mobilised to have South African troops serve in the East African theatre, in order to enable the Union to realise its expansionist territorial aims. Supported by Governor-General Charles Sydney Buxton (1853-1934), this was eventually approved, although not in the form initially hoped for. Lower than expected recruitment meant that South Africa could not ask to control the campaign in the same way it had in German South West Africa. The political situation also prevented Smuts from accepting the role of commander of the forces, and Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930) being appointed to the post instead. When Smith-Dorrien fell ill, the political situation in the Union had stabilised to the extent that Smuts was able to assume the command.

Smuts arrived in East Africa on 19 February 1916, just a week after the South African disaster at Salaita Hill, where 137 Union soldiers lost their lives attacking the German stronghold. He reorganised the forces and started a major drive into German East Africa. His disregard for the rainy season, challenges posed by tsetse fly, and over-extended supply lines, which could not keep pace with the troops, resulted in mixed reactions to his leadership and management of the campaign. In the ten months he commanded, he could not bring the German commander to heel, but managed to occupy most of the German-held territory before handing over the post to General Arthur Reginald Hoskins (1871-1942).

London, 1917↑

Smuts handed over to Hoskins so that he could represent South Africa at the Imperial meetings, which newly appointed British Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) had called in early 1917. Botha did not feel comfortable attending and felt Smuts was better suited to the English political environment.

The British government asked him to stay and help with the British war effort. His appointment was to propel a propaganda coup “proving” Britain’s cause was just, similar to the campaign Smuts had run during the Anglo-Boer War against the British in 1899-1902. He chaired various committees that required him to attend the British War Cabinet meetings as an observer. Smuts did not return to South Africa until after the Treaty of Versailles was signed in August 1919.

It was hoped that Smuts would support the government in getting the generals to consider supporting fronts other than the Western Front in an attempt to defeat Germany. When this did not happen, other roles were found for Smuts. These included dealing with a Welsh miner's strike, the defence of London and the coordination of the various air forces - the latter effort eventually leading to the creation of the Royal Air Force. He declined opportunities to command in Palestine and to intervene in the Republican-Empire divide in Ireland, which was considered to be similar to the situation in South Africa that had transpired between Boer and Briton.

Peace Talks↑

Smuts played an instrumental role in the peace talks of 1919. Initially, during 1916, whilst in East Africa, his requests to take over the administration of Tabora from the Belgians led Britain to question its allies about their war aims. In 1917, he participated in Lord George Curzon’s (1859-1925) Territorial Desiderata Committee. Following Smuts’ suggestion to create an international board to govern captured territory, he entered into discussions with President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) regarding the Mandate system in 1918. Smuts was instrumental in the formation of the League of Nations and was the author of its Charter. During the peace discussions he, rather than Louis Botha, presented South Africa’s case for becoming the mandate authority for German South West Africa. Smuts refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, feeling it was too harsh. However, Louis Botha convinced him to sign it as a sign of South Africa’s status as an independent country, albeit one which continued to exist within the British Empire.

Return to South Africa, 1919↑

Soon after returning to South Africa, Smuts became Prime Minister when his friend, colleague and confidante, Louis Botha, died on 27 August 1919. Without Botha’s mediating personality, Smuts was unable to reconcile the various factions in the Union and lost the 1924 election.

Anne Samson, Great War in Africa Association

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Selected Bibliography

- Hancock, William Keith: Smuts. The sanguine years, 1870-1919, Cambridge 1962: Cambridge University Press.

- Lentin, A.: General Smuts. South Africa, London 2010: Haus Publishing.

- Samson, Anne: Britain, South Africa and the East Africa campaign, 1914-1918. The union comes of age, London; New York 2006: I. B. Tauris; St. Martins Press.

- Smuts, Jan C., van der Poel, J. / Hancock, W. K. (eds.): Selections from the Smuts papers, June 1910 - November 1918, volume 3, Cambridge 1966: Cambridge University Press.

- Woodward, David R.: The Imperial strategist. Jan Christiaan Smuts and British military policy, 1917-1918, in: Military History Journal 5/4, 1981, pp. 130-145.