Early Career↑

Paul Nash (1889-1946) studied at the Slade school of art in London. In the years immediately before the First World War, his artistic preferences were for neo-Romantic nocturnes and visionary landscapes that were indebted to the mystical figuration of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and the Pre-Raphaelites. Although he was aware of the new Modernist movements such as English Vorticism and Italian Futurism, it did not impact on his work until his exposure to combat on the Western Front.

War Artist↑

Nash volunteered for service in his county military unit, the Hampshire regiment. In mid-1917, after two years of home service, he was posted as a subaltern to the St. Eloi sector of the Ypres salient. After two months at the front, he was invalided home after falling into a trench. Convalescing with a broken rib, he learned that many of his fellow officers had been killed in an attack on the enemy redoubt at Hill 60.

Recovering in England, his work took the first of several radical creative turns. Embracing the diagonal dynamism and jagged energy of his Vorticist contemporaries, he abandoned his pastoral visions, replacing them with splintered woods, violated nature, and wasted panoramas. The actualities of the war came as a terrific shock to an artist so deeply imbued with the English pastoral ideal.

An evocative writer as well as an innovative painter, Nash recalled in one letter marching to the front line through the remnants of a recently-shelled wood, when it was little more than “a place with an evil name, pitted and pocked with shells, the trees torn to shreds, often reeking with poison gas.”[1] A few days later, to his astonishment, this desolate and ruinous place was drastically changed. As Nash wrote in his war letters in Outline, it was now a vivid green, bristling with buds and fresh leaf growth:

Such visions were translated into a suite of watercolours and coloured drawings. Exhibitions of his work brought him to the attention of critics who recognized his novel rendition of modern war. It heralded, one wrote, “an actuality, an immediacy, that brought to life everything about the front which people had read and heard, but had found themselves quite unable to visualize.”[3]

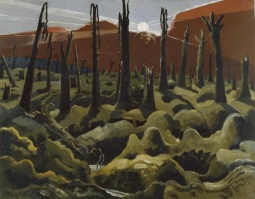

Nash was commissioned as an official war artist by the British government’s War Propaganda Bureau (later the ministry of information) and sent back to the Western Front. Arriving back in the Ypres salient in November 1917, he was spellbound and aghast at the scale of the devastation, particularly the sight of splintered copses and dismembered trees, seeing in their shattered limbs an equivalent to the human carnage that lay all around or even hung in shreds from the eviscerated branches. Accompanied by his batman and chauffeur, Nash travelled behind the front lines and often came under fire, but he was able to produce a collection of powerful drawings and watercolours that captured the dystopian face of modern warfare. In these works, Nash let the devastated landscape express the abominations of the conflict. It was a phantasmagoric world, craters brimming with sulphurous liquid; trees inert and gaunt, failing to respond to the shafts of sunlight; their branches dangling lifelessly like melancholy tresses of hair.

Critical reception was unanimous, applauding a brave new talent. Writing in the foreword to the Void of War exhibition in London in May 1918, Arnold Bennett (1867-1931), the writer and director of propaganda in France, wrote:

Powerful exhibitions of his front line work were staged in London; oil paintings were commissioned for both British and Canadian war memorial schemes. Large oil paintings such as “The Menin Road”, “Void of War”, and “The Mule Track” revealed him to be a major new talent on the European stage. Nash had created a distinctive vision of war, fuelled by an intense anger at the madness of the conflict and its violation of nature.

Post-War Career↑

Nash struggled to find a distinctive voice after the armistice. Describing himself as “a war artist without a war”, he tried to maintain his creative focus. Having developed a new syntax of violent despoliation amidst the vast shapelessness of modern industrialised conflict, he found it difficult to orientate his practice in peacetime. Yet, by fusing continental surrealism with the English Arcadian tradition, he emerged from the 1920s as a highly innovative painter, photographer, and printmaker. His reputation was enhanced considerably by numerous one-man exhibitions and monographs written by leading art historians of the day. He was one of very few official war artists from the Great War who was again commissioned in the Second World War. He died in 1946, aged 57, from heart failure aggravated by an asthmatic condition that may have had its origins in the gas-reeking trenches of the Ypres salient.

Paul Gough, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Bennett, Arnold: Void of war. An exhibition of pictures, London 1918: E. Brown & Phillips, the Leicester Galleries.

- Causey, Andrew: Paul Nash, Oxford 1980: Clarendon Press.

- Cork, Richard: A bitter truth. Avant-garde art and the Great War, New Haven 1994: Yale University Press.

- Eates, Margot: Paul Nash. The master of the image, 1889-1946, London 1973: J. Murray.

- Gough, Paul: Brothers in arms. John and Paul Nash and the aftermath of the Great war, Bristol 2014: Sansom & Co..

- Gough, Paul: A terrible beauty. British artists in the First World War, Bristol 2010: Sansom & Co..

- Haycock, David Boyd: A crisis of brilliance. Five young British artists and the Great War, London 2009: Old Street.

- Malvern, Sue: Modern art, Britain, and the Great War. Witnessing, testimony, and remembrance, New Haven; London 2004: Yale University Press.

- Nash, Paul: Outline. An autobiography and other writings, London 1949: Faber and Faber.