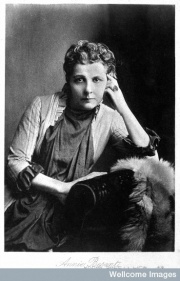

Annie Besant before World War I↑

Annie Besant (b. Woods) was a social reformer, campaigner for women's rights, leading theosophist and supporter of Indian nationalism. Born in London in 1847, she married the clergyman Frank Besant (c. 1841-1917) in 1867, with whom she had two children. In 1873 they legally separated and Besant joined the National Secular Society and the Fabian Society and started to move in the free-thought and socialist circles. She worked closely with Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891) to support and publicize progressive ideas about national education, women's right to vote, birth control, and trade unions. In Great Britain Besant learned important techniques of public campaigning and constitutional protest which she later deployed in the Home Rule movement during the First World War in India.

In the late 1880s Besant joined the Theosophical Society (TS) and moved to India in 1893. After settling in Benares, Besant engaged most notably in religious, educational and social reform activities, such as the establishment of the Central Hindu College in Benares. In 1907 she was elected President of the TS after which she moved to Madras and began to take an active interest in politics once again. In 1913, Besant joined the Indian National Congress and the next year she started two publications: the journal Commonweal and the daily New India, both of which became influential mouthpieces for her political ideas.

Home Rule for India↑

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the national movement in India was weak and split into moderate and extremist factions. The movement had not yet spread across all of India and lacked a wider support from different sections of the society. These circumstances changed during the war as the Indian national movement emerged as a more national, critical and aggressive force. This development was partly due to Besant's efforts, which concentrated mainly on two objectives: one, to unite leaders and ideas in the national movement; and two, to demand self-government for India. While the first seemed to have been successfully achieved by the end of 1915 with the readmission of the revolutionary Hindu nationalist leader, journalist, social reformer and politician Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) and the extremists into the Congress, Besant started to campaign for the latter in 1914.

Political work in India in 1914-1917↑

Initially pointing to the importance of Indian-British friendship and believing that self-government would draw both countries closer together, Besant's demands grew more radical during the war. In December 1914 Besant tried to convince the Congress leaders to accept a scheme for self-government to be presented to the British-Indian government. Her efforts, however, did not evoke any positive responses. Thus, similar to B. G. Tilak, she decided to set up her own political organization to propagate self-government (Home Rule) for India, which according to her scheme included universal franchise at village level for local panchayats (an assembly that traditionally decided on legal, political and/or administrative matters) and a more restricted franchise for different stages of higher legislatures. Besant started a variety of activities such as lecture series and the publication of pamphlets in English and regional Indian languages by the All-India Propaganda Fund and the Madras Parliament. At this point, both she and Tilak still hoped to win over the Congress to initiate a campaign for self-government. However at the 1915 annual meeting, it became clear that the Congress would not adopt such propaganda. Therefore, Besant set up the All-India Home Rule League on 1 September 1916, while Tilak's Indian Home Rule League had already been established in April 1916. With both the Leagues in existence and a growing number of members, Tilak and Besant once again tried to convince the Congress during its Lucknow session in December 1916 to accept Home Rule as its official policy. The Congress rejected this proposal but being greatly influenced by Besant's political work, agreed to start its own reform scheme for Indian self-government together with the Muslim League.

The Government's response to Home Rule↑

Besant's activities and the growing demands for Home Rule and self-government increasingly posed a problem for the British-Indian government, which was occupied with the ongoing war and its effects on the Indian subcontinent. After a long and ambiguous debate on how to counter the Home Rule movement – which posed the question about the differences between the nationalist demands and the government's own ideas about development towards self-government – the government in Delhi decided to arrest Besant and her two close co-workers, Bahman Pestonji Wadia (1881-1958) and George S. Arundale (1878-1945). Their internment in June 1917 caused a nationalist outcry in India and sparked an enormous spread of Home Rule agitation. Confronted with this protest, in August 1917 the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu (1879-1924), announced prospective reforms towards responsible government for India in the form of the Government of India Act 1919, or the so-called Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms. To further conciliate political opinion in India, the three internees were released the following month.

INC-President and afterwards↑

At this point Besant was at the height of her popularity in India and became President of the Indian National Congress in December 1917. Within a year, however, her influence on Indian politics and the national movement had waned. One factor that brought about this change was Besant's presidential speech which was full of authoritarian remarks depicting her presidency as a benediction and arrogating an extended authority for this post. Moreover, her reform-program for India was heavily influenced by theosophist ideas, which were not shared by the majority of the participants. It also became impossible for Besant to retain unity amongst the different sections of the Congress, a unity that was only reinstalled after Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) took over national leadership. Finally, Besant's display of highly ambivalent, changing views regarding important topics, such as the proposed governmental reform scheme, India's support in the war, and the Amritsar massacre, disappointed many former followers. Besant remained a member of the Indian National Congress through the 1920s; however, she no longer played a major role in Indian politics.

Maria Framke, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zürich

Section Editor: Heike Liebau

Selected Bibliography

- Besant, Annie: The future of Indian politics. A contribution to the understanding of present-day problems, Adyar, India 1922: Theosophical Publishing House.

- Lubelsky, Isaac / Lotan, Yael: Celestial India. Madame Blavatsky and the birth of Indian nationalism, Sheffield; Oakville 2012: Equinox Pub.

- Mortimer, Joanne Stafford: Annie Besant and India 1913-1917, in: Journal of Contemporary History 18/1, 1983, pp. 61-78.

- Owen, Hugh F.: Towards nation-wide agitation and organisation. The Home Rule Leagues, 1915-18, in: Low, Donald Anthony (ed.): Soundings in modern South Asian history, Canberra 1968: University of California Press, pp. 159-195.

- Taylor, Anne: Annie Besant. A biography, Oxford; New York 1992: Oxford University Press.