Sea, Land, and Air: The Siege and Fall of Qingdao↑

A request from London triggered Japan’s entry into the Great War. On 7 August 1914, just ten days after the outbreak of World War I, the British Foreign Office asked for Japan’s assistance against German armed merchant vessels in the East China Sea. Whitehall referred to a clause in the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance that established the mutual support of the two countries. Later that day, Foreign Minister Katō Takaaki (1860-1926) and his cabinet colleagues agreed to go to war with Germany.[1]

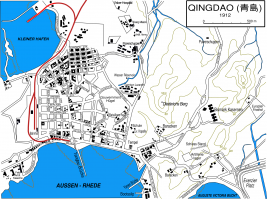

The Japanese government took the British appeal one step further. On 15 August, Prime Minister Ōkuma (1838-1922) issued an ultimatum: Germany must withdraw its fleet from Asian waters and unconditionally hand over its Jiaozhou Bay concession by 15 September. Japan’s move to establish a foothold in China went well beyond the scope of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which was concerned only with mutual defense and did not address unilateral territorial expansion. However, Japanese politicians did not want to waste this “one chance in thousand years” for an advance into continental Asia, especially at a time when the Western powers were busy fighting their war in Europe.[2] The Japanese also could count on China’s noninterference: To avoid the advance of the war into its own territory, the Chinese government had announced its neutrality in early August. Furthermore, repeated British promises for the unconditional return of the German concession’s capital Qingdao to China soothed Chinese worries about the future status of the city.[3] With the ultimatum left unanswered, Japan declared war on Germany on 23 August and dispatched troops to capture the German base at Qingdao, a small peninsula in Shandong Province in northern China.

Before the ultimatum expired, the Germans had prepared for a siege, laying mine barriers and strengthening fortifications against sea and land attacks. The German East Asia Squadron was not at its Qingdao base when the conflict started, so defenders were equipped with only a gunboat, a torpedo boat, and an obsolete cruiser. The Japanese navy, for its part, sent a sizeable fleet of sixty-eight vessels that included six cruisers, thirty-one destroyers and torpedo boats, and—for the first time—a seaplane carrier. The numerical superiority of Japanese ground troops was even more overwhelming. Around five thousand German troops faced a Japanese ground force of nearly 50,000 men, together with a British contingent of about 1,500 soldiers.

The Japanese began a naval blockade on 27 August and, six days later, landed their expeditionary force on Chinese territory. On 4 September, the appearance of Japanese airplanes marked the beginning of almost daily air raids against German positions and vessels. The Germans responded by sending out their naval pilot Gunther Plüschow (1886-1931), who engaged in numerous air combats using his Parabellum pistol. Plüschow also dropped makeshift bombs, which, according to his own account, were made from coffee cans filled with dynamite and scrap metal.[4]

By the end of the month, the Japanese had established a line of siege that completely cut off the peninsula from its hinterland. Japanese warships and land-based heavy artillery started shelling the town. The Japanese launched their final attack on 29 October. With Japanese shelling eliminating most of the German artillery and supplies running low, the German troops surrendered on 7 November.

Even with its limited geographical scope and predictable outcome, the Battle of Qingdao was a harbinger of modern warfare. A pattern had evolved that was soon to wreak havoc on European battlefields as well: Heavy artillery fire bombarded an entrenched enemy while defenders relied on machine guns to fend off advancing infantry. Airplanes as a new weapon proved their worth to watch and strike from the sky, and aerial bombing demonstrated its future potential to inflict material and psychological damage on an unprecedented scale.

The fall of Qingdao also had important diplomatic ramifications. Less than three months after the German surrender, Japan issued the so-called Twenty-One Demands, which forced the Chinese government to recognize Japanese control of the occupied Shandong territory. The demands incited the Chinese public and prompted China’s leaders to secure a place at the postwar negotiations where, after the defeat of Germany, the Shandong question would be settled. Consequently, in one of history’s ironies, China declared war on Germany in August 1917, thus siding with Japan.

Going South: Japan’s Occupation of Micronesia↑

While the Japanese army was still preparing for its first battle with the German forces, the navy set up a two-pronged plan to seek out and destroy the German East Asia Squadron and to take control of the Pacific Islands held by Germany. However, in autumn 1914, the main force of the East Asia Squadron was already out of reach, operating in the eastern Pacific and preparing for a breakthrough around Cape Horn into the Atlantic. Yet control of the South Pacific islands was a key target for the Japanese. Already in 1907, Japan’s Imperial Defense Policy had identified the United States as the Japanese navy’s most probable opponent. By 1912, U.S. planners, for their part, had foreseen a Japanese attack on U.S. bases in the Philippines, with a subsequent naval engagement in the Pacific.[5] In such a scenario, control of the South Pacific islands along the sea route between the U.S. military bases in the Philippines and Guam was of great strategic importance, especially after the opening of the Panama Canal on 15 August 1914, when Japanese anxieties about U.S. dominance in the Pacific increased.

In August and September 1914, the Japanese navy expeditiously set up two detachments for operations in the South Pacific. In mid-September, the First and Second South Seas Squadrons left their harbors in Yokohama and Sasebo. The two task forces steamed on a southeastern course for their 4,000-kilometer voyage to the Marshall and Mariana Islands. Both squadron commanders, Vice Admiral Yamaya Tanin (1866-1940) and Rear Admiral Matsumura Tatsuo (1868-1932), had received strict instructions from Navy Minister Yashiro Rokurō (1860-1930) not to occupy any part of the German territories. Yamaya arrived with his three cruisers and two destroyers at the Jaluit Atoll on 29 September.[6] He ignored the Navy Ministry’s directive and seized the island without encountering any German resistance. When the Navy Ministry ordered immediate withdrawal, Yamaya complied and fell back 400 kilometers to the Eniwetok Atoll.

It seems, however, that Yamaya’s unauthorized action had tipped the scales in favor of the navy’s expansionist faction. On 3 October, the navy’s general staff convinced Navy Minister Yashiro to give the official order for a “temporary” occupation. That same day, Yamaya occupied Jaluit once more, and by 12 October, his squadron had seized the eastern Caroline Islands of Kusaie, Ponape, and Truk.[7] During the same time period, the Second South Seas Squadron’s battleship Satsuma, together with two cruisers, took control of the western Caroline Islands of Yap and the Palaus. On 14 October, with the capture of Saipan in the Mariana Islands archipelago, the occupation was complete.

Unlike the siege of Qingdao, the South Pacific Islands campaign had been short, with very little publicity and no casualties. Most importantly—and again in stark contrast to Qingdao—the occupation’s strategic significance was enormous. Now a numerically inferior Japanese navy was in a position to intercept and weaken the U.S. fleet already on its way to the Philippines before engaging in a final decisive battle. By the end of 1914, the Second South Seas Squadron was converted into the Provisional South Sea Islands Defense Force. With the establishment of such a unit, the Japanese navy not only asserted Japanese control of the region, but also invigorated its proposition for a further “southern advance” in the near future.

Women Soldiers and Flying Aces: Japanese Volunteers in Europe↑

When the carnage on the European battlefields intensified, the Japanese government decided to provide humanitarian relief to its European allies. Since 1890, a well-trained corps of Japanese volunteer nurses had existed for wartime relief. After three years of training, these nurses entered the reserve forces and could be summoned for military service. In September 1914, the Japanese army informed the Vice President of the Japan Red Cross Society, Ozawa Takeo (1844-1926), that the Cabinet had approved the dispatch of Red Cross relief units to Britain, France, and Russia. The Red Cross Society welcomed the opportunity to promote its reputation for humanitarian relief. It quickly put together three squads, each composed of one surgeon and twenty carefully selected nurses, to be sent to Europe on a five-month assignment. The teams left Japan between October and December 1914 to perform their duties in Petrograd (the former Saint Petersburg), Paris, and Southampton. The arrival of the nurses received wide press coverage, and their efforts earned much praise. The host countries subsequently asked the Japanese Red Cross teams to extend their relief work to a period of up to fifteen months.[8]

Several Japanese fought for the French World War I flying corps. Some of them became part of the new myth of the fighter aces who chased the enemy high above the trenches of the stalemated armies. Shigeno Kiyotake (1882-1924), a Japanese nobleman and accomplished pianist, joined the French flying corps in December 1914.[9] With two confirmed and six unconfirmed downings of German aircraft, Shigeno joined the exclusive league of French flying aces and received the Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur, France’s highest decoration. Kobayashi Shukunosuke (1892-1918) received his brevet de pilote, the French pilot’s license, in December 1916. He died in combat during the 1918 Spring Offensive and was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre.[10] A number of Japanese volunteer pilots also played an important role in the transfer of air strategy and aviation technology to Japan. Isobe Onokichi (1877-1957) was another highly decorated pilot, cited for “exemplary military qualities in the Squadron by demonstrating his aggressiveness in combat.”[11] Upon his return to Japan, Isobe published the book Sora no tatakai (The war in the air), wherein he emphasized the national importance of air power and civil air defense. Ishibashi Katsunami (1893-1923) used his knowledge of French aircraft design to build racing airplanes in Japan, while Moro Goroku (1889-1964) embarked on a distinguished career as a Kawasaki aircraft engineer.

“Good Seamanship and Greatest Rapidity of Action”: Japanese Warships in the Mediterranean[12]↑

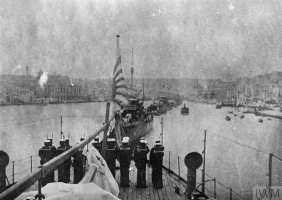

Already in the early stage of the war, Britain, France, and Russia repeatedly asked for Japanese support in the European theatre. Initially, the Japanese government refused to send any troops. Foreign Minister Katō argued that such a military expedition was extremely unpopular and would run counter to the Japanese military’s purpose of protecting Japan from an outside enemy.[13] When the new cabinet under Terauchi Masatake (1852-1919) was formed in autumn 1916, the government was more inclined to consider Allied requests—on one condition: The new foreign minister Motono Ichirō (1862-1918) asked the British to back Japan’s claims to the recently acquired German territories in Shandong and the South Sea. The minister shrewdly suggested that such a move would lead to a more cooperative cabinet. On 1 February 1917, Germany announced it would resume its unlimited submarine warfare and intensify attacks on Allied ships. By mid-February, the British government agreed “with pleasure to the request of the Japanese Government for an assurance that they will support Japan’s claim.”[14] The Japanese reacted quickly. On 13 April 1917, Rear-Admiral Satō Kōzō (1871-1948) arrived with his Second Special Squadron in Malta, the headquarters of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet.

The seventeen warships of the squadron were to provide protection for Allied ships against attacks from German and Austro-Hungarian submarines operating from bases along the Eastern Adriatic coast, in the Aegean Sea, and at Constantinople. The Japanese cruisers and destroyers thus patrolled the main sea routes linking Alexandria, Marseilles, Taranto in Italy, and Thessaloniki that were vital for the transport of troops and supplies. The Japanese navy played a crucial role in one of the most spectacular rescue missions of World War I. On 4 May 1917, the troopship Transylvania was hit by a German torpedo. With the help of the destroyers Matsu and Sakaki, around 3,000 of the nearly 3,300 persons on board were saved.

During their deployment in the Mediterranean, the Japanese escorted twenty-one British warships and more than 700 Allied transport ships, which altogether carried more than 500,000 passengers and sailors. More than 7,000 crew members and passengers who would otherwise have been casualties of submarine attacks owed their lives to Japanese rescue missions.[15]

The British highly esteemed the Japanese exploits. The commander of the Malta base, George A. Ballard (1862-1948), commended Rear-Admiral Satō’s dedicated and quick response to all British requests. He was also impressed by the high operational rate of the Japanese squadron, which even surpassed that of its British counterparts.[16] In return, the Japanese eagerly absorbed British know-how and technology for the location, evasion, and destruction of submarines. Upon its return to Japan, the Second Special Squadron brought seven German submarines as war trophies. These U-boats incorporated the latest German technology and greatly contributed to the Japanese navy’s ambitious program of building a submarine fleet for intercepting U.S. vessels in the Pacific.

Much Ventured, Nothing Gained: Japan’s Siberian Intervention↑

With the impending collapse of the Eastern Front after the October Revolution, the French General Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) proposed a military intervention in Siberia. On 3 December 1917, he suggested deploying Japanese and U.S. troops to the Pacific seaport of Vladivostok, seizing control of the Trans-Siberian Railway, crossing the Urals, and re-establishing the Eastern Front. Even though the Japanese cabinet rejected this bold plan, officials of the Japanese army took up the idea of sending troops to Siberia. In their view, such a move would expand Japan’s sphere of influence and secure Japanese interests and access to resources. Vice-Chief of the General Staff Tanaka Giichi (1864-1929) even envisioned an autonomous state east of Lake Baikal as a buffer area.[17]

The issue of an intervention in Russia’s Far East gained momentum when, in early 1918, the Japanese learned that the British cruiser Suffolk was on its way to Vladivostok. Prime Minster Terauchi immediately dispatched the cruiser Iwami to forestall any unilateral British action. The Japanese warship arrived on 12 January 1918, two days before the Suffolk. On 4 April, after an attack on Japanese civilians, 500 Japanese marines occupied Vladivostok and established Japanese control over the city for the next four months.

In July 1918, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) asked for 7,000 Japanese troops to join an international coalition that was to confiscate a large stockpile of weapons and ammunition and to relieve around 50,000 anti-Bolshevik Czech and Slav nationalists who hoped to evacuate via Vladivostok. The Terauchi Cabinet was more than eager to comply. On 18 August, the soldiers of the 12th Division landed at Vladivostok and marched north to capture Khabarovsk. Two days later, the 7th Division left its bases in South Manchuria, followed the Chinese Eastern Railway via Manchuli, and occupied Chita. Both units carried with them a total of twenty-one aircraft for reconnaissance, propaganda, and bombing missions.[18] The two divisions advanced along the Trans-Siberian Railway to connect at Blagoveschensk on 19 September.[19] By the end of October, the Japanese army had deployed over 70,0000 soldiers—ten times more than initially agreed upon—who now controlled the Trans-Siberian Railway all the way from the Sea of Japan to Lake Baikal.[20]

While Japan’s military fought its war of expansion abroad, widespread unrest erupted at home. Wartime inflation had led to rising food prices, sparking violent protests between July and September 1918. The army deployed more than 100,000 troops to put down the riots, and Prime Minster Terauchi resigned. Tanaka Giichi, the newly appointed war minister, then decided to withdraw half of the Japanese troops in Siberia by December 1918.

The remaining Japanese units engaged in fighting with Bolshevik partisans, resulting in heavy losses on both sides. By late 1919, the Soviet Red Army had significantly weakened anti-Bolshevik forces and one by one the British, U.S., and Czech units of the coalition forces withdrew. In May 1920, Russian partisans killed almost 700 Japanese civilians and soldiers at Nikolaevsk. The massacre made the Army General Staff decide to continue the occupation of Eastern Siberia. However, the intervention’s costs continued to escalate, and its popular support soon evaporated. Finally, in June 1922, Prime Minister Katō Tomosaburō (1861-1923) announced the withdrawal of Japanese troops.

The Siberian intervention was a dismal failure. Nearly 1,500 Japanese servicemen lost their lives in combat, and 600 soldiers died from cold or disease. The Japanese treasury spent ¥600 million on the venture.[21] Japan’s failed effort to gain control of Eastern Siberia increased U.S. misgivings about Japanese expansionism and deeply antagonized the Soviet Union. It also damaged the trust of the Japanese people in their government’s ability to end an unpopular campaign in good time.[22] Furthermore, the army’s loss of prestige weakened its political influence and opened the way for cuts in the military budget, disarmament, and troop reduction.[23]

Conclusion↑

Japan’s Mediterranean exploits and volunteer activities enhanced the country’s prestige among its allies. With its expansion into the Chinese mainland, the southern Pacific, and the Transbaikal region, the Japanese military eventually controlled an area nearly as vast as the World War II Pacific War theater.[24] By the end of World War I, Japan clearly belonged to the great powers (rekkoku) with a place at the table for the Paris Peace Conference. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles awarded the German South Pacific islands to Japan as Class C mandated territories under the League of Nations. It also granted Japan all German rights in the Jiaozhou Bay concession, very much to the disillusionment of the Chinese delegates, who subsequently refused to sign the treaty. In addition, the treaty gave Japan access to the latest German military technology, including not only submarines, but also airplanes, aero engines, and other aeronautical material.

However, Japan’s expansionism came at a price. By the early 1920s, relations with Britain and the United States had deteriorated, and Japan turned from an ally to an opponent that threatened British and U.S. interests in South East Asia and the Pacific. Japan’s foothold in China was short-lived. During the 1922 Washington Conference, Japan’s representatives gave in to U.S. demands and returned Qingdao to China. Furthermore, Britain yielded to U.S. pressure, and in June 1923, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance came to an end. Japan’s continental and southern expansion during World War I not only isolated the country from its erstwhile allies, but also set an ill-fated precedent for a conflict that was to bring even more death and destruction.

Jürgen Melzer, Yamanashi Gakuin University

Section Editors: Akeo Okada; Shin’ichi Yamamuro

Notes

- ↑ Nish, Ian: Japan and the Outbreak of War in 1914, in: Collected Writings of Ian Nish, part 1, Richmond 2001, pp. 173–88.

- ↑ Unattributed quote in Ibid., p. 182.

- ↑ For details, see Xu, Guoqi: The Great War in China and Japan, in Best, Antony / Frattolillo, Oliviero (eds.): Japan and the Great War, New York 2015, pp. 13-35.

- ↑ Plüschow, Gunther: My Escape from Donington Hall, preceded by an account of the siege of Kiao-Chow in 1915 [sic], London 1922, p. 68.

- ↑ Miller, Edward S.: War Plan Orange. The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945, Annapolis 1991.

- ↑ Kaigun Rekishi Hozonkai: Nihon kaigunshi [History of the Japanese Navy], volume 2, Tokyo 1995, p. 315.

- ↑ Hirama, Yōichi: Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun [World War I and the Japanese Navy], Tokyo 1998, p. 62.

- ↑ Araki, Eiko: Women Soldiers Delegated to Europe. The Japan Red Cross Relief Corps and the First World War, in: Osaka City University Studies in the Humanities 64 (2013): pp. 5–35.

- ↑ Hiraki, Kunio: Baron Shigeno no shōgai [The life of Baron Shigeno], Tokyo 1990.

- ↑ Ritsumeikan Shishiriyō Center.

- ↑ Mikesh, Robert C. / Shorzoe, Abe: Japanese Aircraft. 1910–1941, London 1990, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Quote taken from The London Times: The Times History of the War, London 1919, p. 458.

- ↑ Hirama, Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun, p. 211.

- ↑ Quoted in Nish, Ian: Alliance in Decline. A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1908–23, London 1972, p. 207.

- ↑ Kaigun Rekishi Hozonkai, Nihon kaigunshi, p. 350; Hirama, Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun, p. 217.

- ↑ Hirama, Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun, p. 218.

- ↑ Humphreys, Leonard A.: The Way of the Heavenly Sword. The Japanese Army in the 1920’s, Stanford 1995, p. 26.

- ↑ Nihon Kōkūkyōkai: Nihon Kōkūshi [The history of Japanese aviation], volume 1, Tokyo 1936, p. 263.

- ↑ Osaka Mainichi Shinbun evening edition, 20 September 1918.

- ↑ Dunscomb, Paul E.: Japan’s Siberian Intervention, 1918–1922. A Great Disobedience Against the People, Lanham 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 192.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 5.

- ↑ Drea, Edward J.: Japan’s Imperial Army. Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945, Lawrence 2009, p. 145.

- ↑ Hata, Ikuhiko: Continental Expansion, 1905-1941, in: Hall, John W. et al.: The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6. The Twentieth Century, New York 1988, p. 281.

Selected Bibliography

- Asada, Sadao: From Mahan to Pearl Harbor. The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States, Annapolis 2006: Naval Institute Press.

- Nihon kaigunshi (A history of the Japanese Navy), volume 2, Tokyo 1995: Kaigun Rekishi Hozonkai, 1995.

- Nihon Kōkūshi (A history of Japanese aviation), volume 1, Tokyo 1936: Nihon Kōkūkyōkai, 1936.

- Burdick, Charles Burton: The Japanese siege of Tsingtau. World War I in Asia, Hamden 1976: Archon Books.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and national reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Drea, Edward J.: Japan's Imperial Army. Its rise and fall, 1853-1945, Lawrence 2009: University Press of Kansas.

- Dunscomb, Paul: Japan's Siberian intervention, 1918-1922. A great disobedience against the people, Lanham 2011: Lexington Books.

- Frattolillo, Oliviero / Best, Antony: Japan and the Great War, New York 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hirama, Yōichi: Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun. Gaikō to gunji to no rensetsu (World War I and the Japanese Navy. The connection between diplomacy and military affairs), Tokyo 1998: Keiō gijuku daigaku.

- Hosoya, Chihiro: Shiberia shuppei no shiteki kenkyū (A historical study of the Siberian Intervention), Tokyo 2005: Iwanami Shoten.

- Morley, James William: The Japanese thrust into Siberia, 1918, New York 1954: Columbia University Press.

- Peattie, Mark R.: Nan’yō. The rise and fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945, Honolulu 1988: University of Hawaii Press.

- Saitō, Seiji: Nichidoku Chintao sensō (The Japanese-German war over Qingdao), Tokyo 2001: Yumani shobō.

- Schencking, J. Charles: Making waves. Politics, propaganda, and the emergence of the imperial Japanese navy, 1868-1922, Stanford 2005: Stanford University Press.

- White, John Albert: The Siberian intervention, Princeton 1950: Princeton University Press.

- Yamamuro, Shin’ichi: Fukugō sensō to sōryokusen no dansō. Nihon ni totte no Daiichiji Sekai Taisen (Faultline between complex and total war. World War I from the perspective of Japan), Kyoto 2011: Jinbun shoin.